We return to Nam with Oliver Stone’s 1986 multiple Oscar winner (Best Film, Best Director, etc), based on his personal experiences.

At fifteen, I drank my first full can of beer, on a rainy foreshore trail with three friends, on our way to a movie: Platoon. First it riveted me. Very quickly it confronted me. When the Americans entered a village thought to be harbouring Vietcong, it alienated and repelled me.

My face whipped away when a soldier swivelled and struck a peasant’s face with a rifle butt. The ensuing sound – a methodical mashing – was sickening. It seemed to be happening right in front of me. Platoon was unlike anything I’d been exposed to. Unnerving scenes didn’t end when you wanted them to. They protracted. They made you look again. As Platoon progressed, the story seemed to be making less and less sense. Movies were supposed to make perfect sense. Eventually, it lost me. For the first time, a movie just cut me loose. The confusion and ear-splitting chaos were too much.

Platoon was not the first Vietnam War film. But Oliver Stone’s film was the first earnest attempt to show what that war looked, sounded and felt like (so far as is possible) up close. The undertaking carried a very high degree of difficulty. America’s Vietnam venture had been a cataclysm of needless suffering. Any sincere film would have to grapple with something earlier war movies generally had not: shame, which is to say, complexity. Where Second World War movies had often ended with a sense of wholeness – evil had been vanquished – no Vietnam War film would be afforded any such conceit.

Platoon is set the year things began to really fall apart for the Americans in Vietnam: 1968. Chris Taylor (Charlie Sheen) arrives with little idea how draining his days and nights here will be and no inkling that he will be a participant in anything deplorable, let alone depraved. The first things we see through his squinting eyes are those bulging body-bags. The shot is purposely perfunctory. They’re just lumped, interchangeable with carcasses leaving an abattoir.

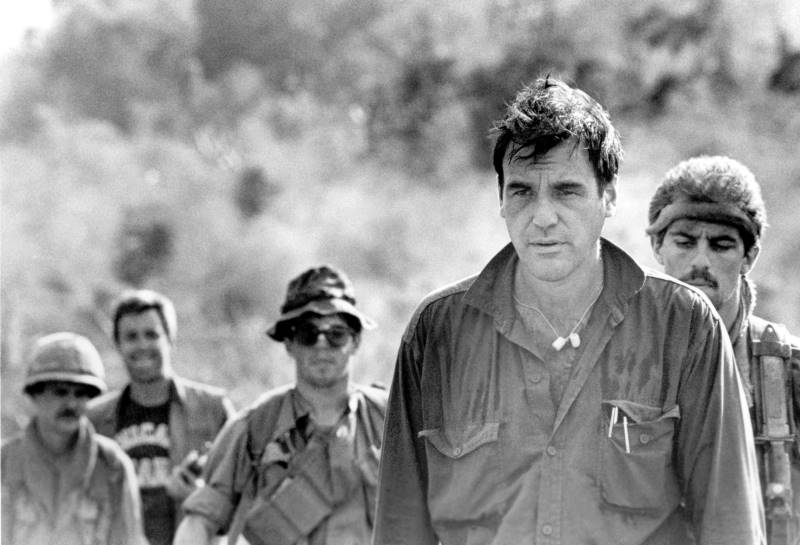

The other thing he sees is the grey, spectral face on a living soldier, leaving: a face branded to millions of moviegoers’ memories. He looks as if he’s been tortured in seven circles of hell and paid his escape with a pint of blood. Stone shows those eyes meeting Taylor’s in a strange, sustained, seemingly preordained forewarning: an eerie effect that could not possibly have been realised with dialogue.

For all Platoon’s kinetic energy, it’s the faces that stay with us. Who could forget the anguish and agonised incomprehension all over the face of the peasant as Taylor, screaming obscenities, fires into the dust around his one foot. Who could forget the pitiless eyes of Barnes (Tom Berenger) as he clamps the mouth of a screaming soldier. “Shut up and take the pain. Take the pain.” (A question for your next road trip: of Sergeant Barnes in Platoon and Freddie Kruger in Nightmare on Elm Street, who has the friendlier face?)

Barnes is interesting. Tom Berenger does everything an actor possibly can, within the role’s limits. But it is a very constrained role. Barnes is almost caricature. Arguably, possibly, just maybe, it becomes Platoon’s Achilles heel. Except for one small problem: Stone is on the record as saying Barnes is based on a man he served under in Vietnam, and that as a writer he did not embellish that man’s mania one iota. That could well be true. But the much-remembered “I am reality” line is more than a bit hammy, and somehow beneath the film’s efforts elsewhere.

Some of Platoon’s detractors have said that Barnes hunting Sergeant Elias (Willem Dafoe) feels forced, even a bit desperate, as plot goes. They have a point. But had it been excluded, the film would’ve been practically shapeless. A purist for veracity might say that’s exactly how a war movie should be. But if truth was the only thing a filmmaker had to consider, and had to follow it all the way every time, every second scene in a film about jungle warfare would be shot in blindfold black.

Ultimately, Stone uses Barnes hunting Elias to illustrate the US military machine not just malfunctioning but self-sabotaging. Fair enough. It’s true, some American soldiers did injure and even kill each other, as the war elongated. It might also be true that Platoon gave an inaccurate impression that it was the rule, rather than the exception.

Stone’s sincerity has its essence in the film’s unobtrusively sombre score. It comes at unexpected moments, and goes again, rises and recedes, haunts the film. Listen to the strains as the soldiers leave the blazing village. It seems to be expressing the villagers’ heartache as much as it is expressing the shame and heartsickness that the more decent-hearted of the soldiers will eventually have to reckon with. Whether a string composition could ever express the villagers’ full feelings – including for some, the wish for retribution – is another matter. A score can only do so much. And that symphony does plenty. It’s looking into the perpetrators’ future, as well as their immediate present, and there’s personal devastation looming.

Other times, Platoon’s use of sound is perfectly simple. Listen to the single, quietly piercing note when Taylor, on watch, eyes his weapon on the forest floor, but can’t move a muscle. The sound amplifies Taylor’s swelling dread. The staccato baritone heartbeat intensifies the effect.

Atmospherically, Platoon is dense, replete with dust and marauding mosquitoes and marijuana miasma and mist and pissing rain. Background bird-sounds pepper anxious pauses. Half-heard two-way radio snatches interject, weirdly hypnotic in half-light. “dingo dingo river 6 . . . ice shackles . . . alpha whiskey foxtrot . . . whiskey . . . foxtrot . . . What’s the delay up on point?”

If Platoon has a hidden weakness, it’s an oddly excusable one. Brace for something stupidly silly now. Some will argue that this is not a weakness but a strength, in an intensely visual medium. It is this: too many of the soldiers look too stylish. The personal touches to the combat gear are almost excessive. Barnes’ head scarf, King’s bullet-bling necklace, Taylor’s raspberry bandanna and Junior’s knitted hat may have been historically accurate but seen altogether, on the most charismatic actors of the day, it can be distracting.

If you’re yet to see Platoon, it’s not a friendly, distracting movie. It’s a horror movie, of a kind. More than that, it documents the intense fear and pain and muddled beliefs synonymous with a time and place. The line from Forest Whitaker’s mouth, “I don’t know, brothers, but I’m hurting real bad inside,” is not sophisticated writing, but there it is, etched. In 2023, it echoes.

That village interrogation scene disturbed the hell out of me at fourteen and disturbs the hell out of me now. Its emotional ferocity was the antidote (the flipside, at least) to the image of Tom Cruise and Val Kilmer slapping palms in Top Gun. It’s said: Look at what war exacts from everyday people living decent everyday lives. If you can watch that chilling scene without flinching, you’re a hard nut to crack. Platoon had its faults. But only a preternatural stoic would deny its weird power.

https://www.filmink.com.au/youre-the-one-whos-nuts-man-revisiting-platoon/”>

#Youre #whos #nuts #man #Revisiting #Platoon #FilmInk