In late February 2022, days after Russia launched its invasion of Ukraine, Russian and Ukrainian officials met in Belarus, opening a diplomatic channel. Russian troops had advanced towards Kharkiv in the northeast and Kherson in the south, but if Moscow expected a quick victory, it was mistaken.

The talks that began in Belarus continued under Turkey’s mediation, culminating in a meeting in Istanbul on March 29, 2022. Ahead of the talks, Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan said Ukraine was ready to renounce NATO membership and recognise Russian as an official language. Soon after the Istanbul meeting, Russia announced that it would pull back troops from the Kyiv and Chernihiv fronts as a “diplomatic gesture”. It later emerged that Russian and Ukrainian officials had tentatively agreed on the outlines of an interim settlement. According to a September 2022 essay in Foreign Affairs by Fiona Hill and Angela Stent, both former U.S. foreign service officials, it was decided that Russia would agree to withdraw to its pre-war position (meaning it would keep Crimea, annexed in 2014, and that pro-Russian rebels would control parts of Donetsk and Luhansk). In return, Ukraine would pledge not to seek NATO membership and instead receive security guarantees from a group of countries. According to Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov, Moscow and Kyiv were ready to draft an agreement based on the Istanbul framework.

However, the Istanbul process collapsed. Western governments were hesitant to provide the security guarantees Ukraine demanded. According to Mr. Lavrov, then British Prime Minister Boris Johnson visited Kyiv in early April and “told them to continue to fight”. Ukrainian President Volodimir Zelenskyy also appeared emboldened by Russia’s withdrawal from the Kyiv area, which he interpreted as a sign of weakness. Naftali Bennett, the former Israeli Prime Minister who was also part of the negotiations, later said Russia and Ukraine had come close to making concessions that could have ended the conflict, but Mr. Johnson persuaded Mr. Zelenskyy to not back down. Ukraine chose to continue to fight, forcing Russian troops to withdraw from Khakiv and later Kherson. Russian President Vladimir Putin, in turn, doubled down — formally annexing four more Ukrainian territories and launching a partial mobilisation. The stage was set for a long war.

Trump’s plan

Almost four years later, another peace plan, this time pushed by the Donald Trump administration, is being circulated among all parties. The 28-point plan appears even less favourable to Ukraine than the Istanbul framework. Kyiv now faces pressure on the frontline where Russian troops are making slow but steady gains; from the U.S., which wants Ukraine to make concessions; and at home where a corruption scandal has rocked the Zelenskyy regime.

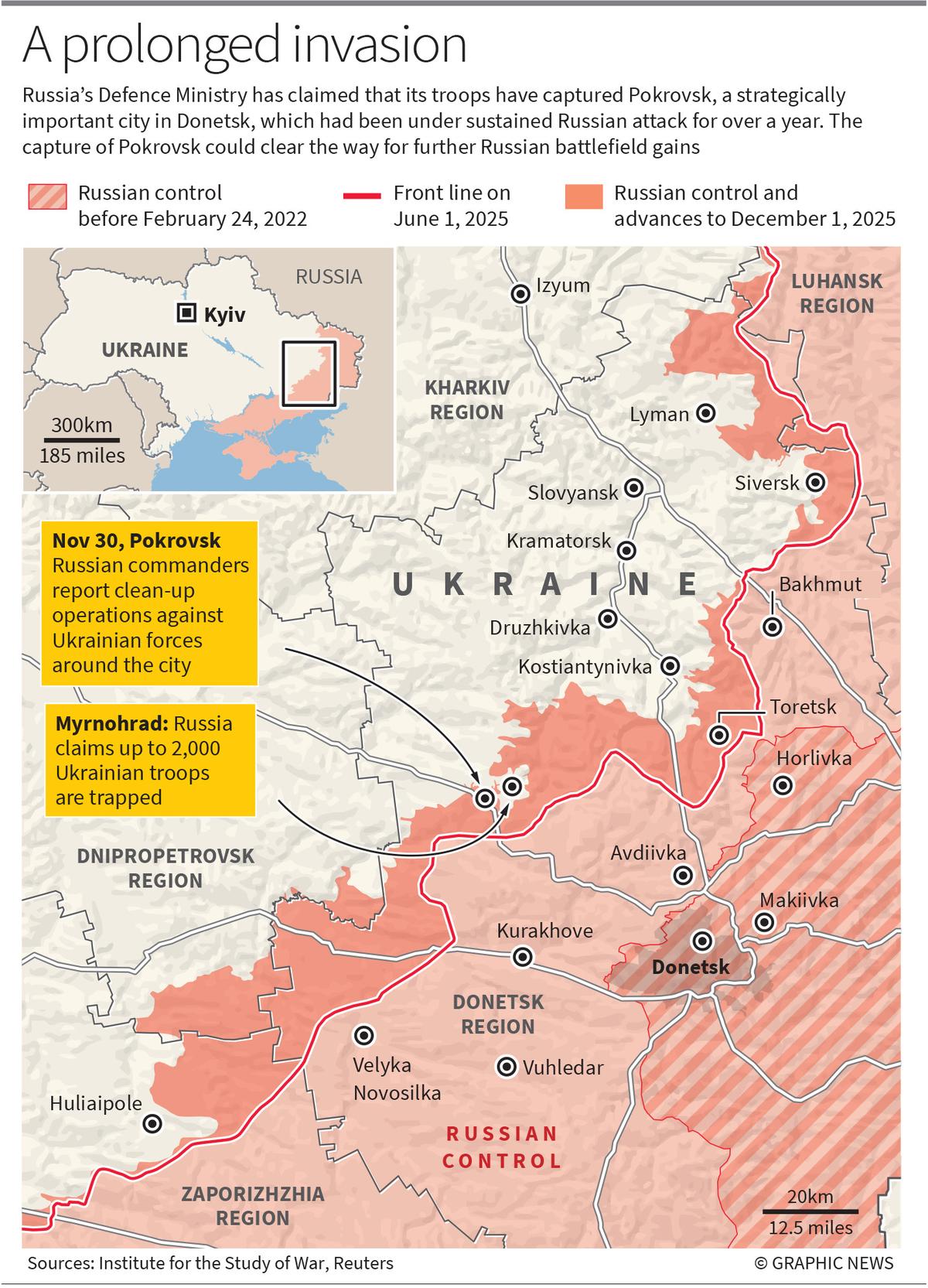

According to Mr. Trump’s draft plan, Crimea, Luhansk and Donetsk will be recognised “as de facto Russian”. Russia controls the whole of Crimea and the whole of Luhansk, but only about 80% of Donetsk. As per the plan, Ukraine will have to withdraw troops from Donetsk. The line of contact in Kherson and Zaporizhzhia, two other provinces Russia has annexed and partly controls, will be frozen — which means Russia will keep the territories it has captured. Russia will relinquish the territories it has seized other than the five oblasts (say, in Kharkiv and Ddnipropetrovsk) in return for Ukraine’s withdrawal from Donetsk. Ukraine will also have to limit the size of its armed forces to 6,00,000 personnel.

The most contentious point, besides territory, in the war was the role of NATO. Russia has consistently opposed Ukraine becoming a member of the trans-Atlantic nuclear alliance, which was founded during the Cold War. As of now, Ukraine doesn’t have a pragmatic path towards NATO membership. The Trump administration has also repeatedly stated that Ukraine was unlikely to be a NATO member. While Kyiv had not given up its desire to join the bloc, now, according to the Trump plan, Ukraine should enshrine in its Constitution that it will not join NATO, and the alliance should include in its statutes that Ukraine will not be admitted in the future (but Ukraine can join the EU). “It is expected that Russia will not invade neighbouring countries and NATO will not expand further,” reads another point in the plan. Russia and NATO will also initiate dialogue, under the mediation of the U.S., to resolve “all security issues”.

If peace prevails, the U.S. promises to reintegrate Russia into the global economy. Sanctions could be lifted and the country could rejoin the G8 grouping (Russia was expelled after the annexation of Crimea), and enter a long-term economic cooperation agreement with the U.S. Moscow will have to enshrine in law its policy of non-aggression towards Europe and Ukraine. While the 28-point proposal says Ukraine will receive “reliable security guarantees”, it doesn’t offer details about the promise. The Trump administration has now circulated another draft agreement dealing only with the security part. The three-point plan, which needs the approval of Ukraine, Russia, the U.S., the EU and NATO, promises NATO-style security assurances to Ukraine for up to 10 years, which can be renewed by mutual agreement. A significant and sustained armed attack by Russia on Ukraine “shall be regarded as an attack threatening the peace and security of the transatlantic community,” reads the document.

Facts on the ground

The Trump plan offers an initial outline to restart talks. While the proposal addresses both Ukraine’s future security and Russia’s stated concerns — including NATO’s eastward expansion — it is widely seen as favouring Moscow. If implemented, Ukraine would have to cede territory, recognise Russian control of its regions and abandon NATO aspirations, while Russia would be reintegrated into the global political and economic mainstream. Mr. Zelenskyy’s initial response was that Ukraine was being forced to choose between its dignity and a close partner (the U.S.). Nevertheless, Ukrainian officials held talks with European and U.S. officials to add their inputs to the Trump proposal.

While efforts to find a political solution continue, the facts on the ground have shifted significantly since the March 2022 Istanbul talks. At that time, Russia, whose initial attack had not gone according to plan, was on the back foot, and appeared willing to make concessions. But after suffering tactical setbacks in Kharkiv and Kherson, Russia regrouped and restructured its forces and shifted to a long-term war strategy. Over the past four years, Ukraine has received some of the West’s most advanced defensive and offensive systems, including F-16s, Patriot missile defence systems, main battle tanks, armoured vehicles and medium to long range rockets, besides large quantities of ammunition. Yet, they couldn’t stop Russia’s grinding advances. On Monday, Russia’s Defence Ministry announced that its troops captured Pokrovsk, a strategically important city in Donetsk, which had been under sustained Russian attack for over a year. The capture of Pokrovsk and Russian advances in Kupiansk (in Kharkiv) could clear the way for further Russian battlefield gains.

When Joe Biden was the U.S. President, Washington’s policy was to support Ukraine “as long as it takes”. There was a broad consensus between the U.S. and Europe that sustained military and economic assistance to Kyiv, combined with economic sanctions on Moscow, could eventually weaken Russia’s war effort — or at least push Mr. Putin to seek a settlement that was not entirely favourable for Russia. But Ukraine’s 2023 counteroffensive, aimed at recapturing lost territories, proved a decisive failure, effectively closing off the military option. The return of Mr. Trump to the White House in early 2025 meant that the trans-Atlantic consensus on Ukraine was broken. Mr. Trump saw the conflict as a lost war, and began shifting the burden of supporting Ukraine onto Europe. He believes that once the war is concluded, Washington and Moscow could reopen a new chapter in their historically troubled relationship.

Some in the U.S. strategic community also argue that Washington could attempt a ‘Reverse Kissinger’— drawing Russia away from its deepening strategic partnership with China, the U.S’s principal global rival.

Zelenskyy’s dilemma

The Trump plan leaves Mr. Zelenskyy in a difficult position. The Ukrainian leader, whose term expired last year, continues to cling on to power under martial law. Last week, Mr. Zelenkyy’s Chief of Staff Andriy Yermak resigned after a corruption scandal shook the regime. The economy is being propped up by aid from the West, and parts of the country are grappling with power outages as repeated Russian strikes target Ukraine’s electricity grid. On the battlefield, the loss of Pokrovsk has marked a major setback.

Mr. Zelenskyy once insisted that peace would be possible only if Russia withdrew from all seized territories, including Crimea. Today, he is prepared to accept a ceasefire along the current frontline, which would leave more than 20% of pre-2014 Ukraine in Russian hands. In Istanbul, there was at least an outline for a possible agreement. That moment has passed.

Now, with the Trump plan, Ukraine finds itself in a much weaker position. It doesn’t have a clear path towards military victory. Worse, it risks losing the support of Washington.

European countries, chiefly Germany, the U.K. and France, have pledged continued support. But those assurances carry limited weight if the U.S. exits the support architecture.

If Mr. Zelenskyy accepts the deal Mr. Trump is offering, it would amount to conceding victory to Russia. He could also face serious political consequences at home. If he rejects it, Ukraine risks losing more territory in a prolonged war.

www.thehindu.com (Article Sourced Website)

#peace #Ukraine #Explained