The story so far:

After the February 2021 coup, the Myanmar military (Tatmadaw) promised to hold elections and restore civilian governance quickly. Even after four years and 10 months, the Tatmadaw has not established stable political conditions. And yet, it is conducting three-phase elections for the Union Parliament and provincial legislatures. The first phase was held on December 28, while the second and third phases are scheduled for January 11 and January 25 next year.

What is the context in which the elections are being held?

The elections are taking place in a highly stressed political context. After the coup, the civilian leadership, despite a massive electoral victory in the 2020 elections, is under detention, which includes State Counsellor and Chairperson of the National League for Democracy (NLD) Aung San Suu Kyi, leaders from various political parties, and democracy activists. The Tatmadaw also reconstituted the Union Election Commission (UEC) with personnel favourably disposed towards it.

The coup prompted an armed resistance movement led by the People’s Defence Forces and Ethnic Armed Organisations (EAOs). Despite deploying harsh military tactics, including against the civilian population, the Tatmadaw has lost control of large parts of the country. For instance, in Rakhine province, the Arakan Army controls large areas, whereas the Tatmadaw holds urban centres such as the Sittwe port.

According to the UEC, elections will not be conducted in nine parliamentary constituencies of the Pyithu Hluttaw (lower house), two parliamentary constituencies of the Amyotha Hluttaw (upper house), and nine constituencies of the Region/State Hluttaw (provincial legislatures) due to the prevailing security situation. It should be noted that even in constituencies where the Tatmadaw claims to organise elections, large tracts of rural areas are not witnessing polling.

Even in areas where the military’s writ runs, it is resorting to coercive tactics to quell criticism of the elections. Approximately 229 people were arrested under the Election Protection Law, enacted in July 2025. Unlike previous elections, the Tatmadaw is using electronic voting machines. Given the history of blatant tampering with the electoral process, the use of machine-based voting will not inspire much confidence.

Due to political instability and the consequent economic hardships, large numbers of people have migrated out of Myanmar. Specifically, many young people have fled the country to avoid conscription. Given that the election outcomes are perceived to be predetermined, there is little incentive for migrants to return to participate in the electoral process. Not surprisingly, voter turnout in the first phase of the election was very low.

Which parties are contesting the elections?

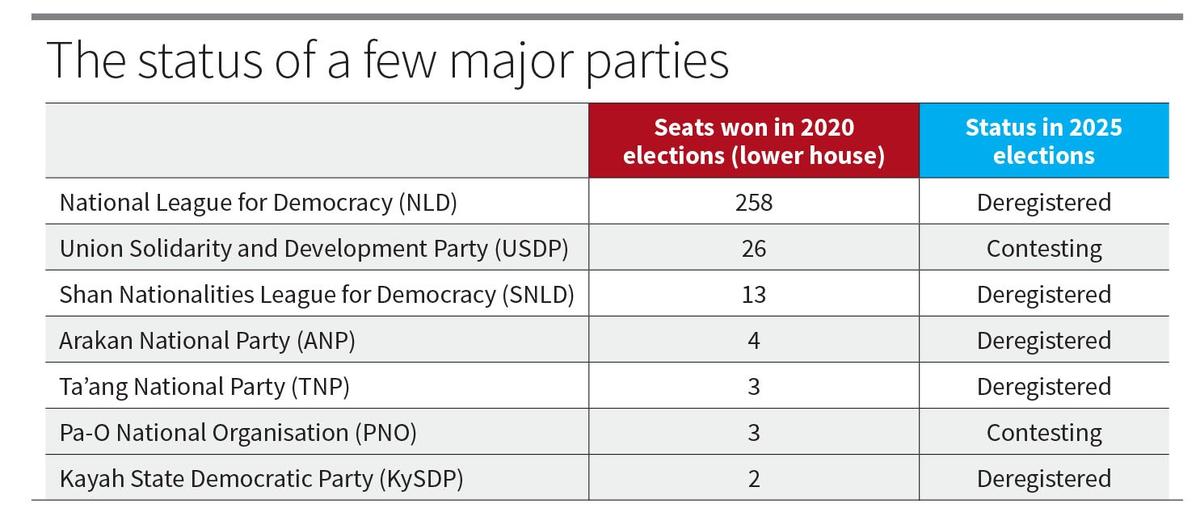

According to the UEC, six national parties and 51 provincial parties are registered to contest the elections. With its leadership under prolonged detention and its refusal to register under the new, stringent Political Parties Registration Law, the NLD, the largest party, was dissolved by the UEC.

In addition to the NLD, other parties with a strong regional presence are also not contesting the elections. For instance, in Rakhine province, where the Tatmadaw’s ability to organise elections is minimal, the Arakan National Party’s (ANP) application for re-registration was rejected by the UEC. A similar fate also befell the Shan Nationalities League for Democracy (SNLD) and a few other parties. With the deregistration of large national and regional parties, military-supported parties such as the Union Solidarity and Development Party (USDP) have no genuine competitors.

Furthermore, resource constraints are unlikely to allow other parties to contest a large number of seats. Only the USDP has the wherewithal to contest the largest number of seats, and it is likely to emerge as the largest party. Even prior to the election, it is estimated that the USDP is winning more than two dozen parliamentary constituencies uncontested. Early reports from the first phase also hint at USDP wins.

There are other parties, such as the National Unity Party (NUP), which also receive support from the military. Given that the military has 25% of the seats in the legislature and military-dominated parties will also have a stronger presence, the Tatmadaw will be in complete control of the legislative agenda.

How does the electoral system and reform agenda shape the outcome?

The current elections are being held under a first-past-the-post (FPTP) and proportional representation (PR) systems. The lower house will elect representatives under the FPTP system. On the other hand, the upper house and State legislatures will elect representatives under PR as well as under the FPTP.

The Tatmadaw deployed a proportional representation system to ensure that no party secures a significant majority of elected seats in both houses of Parliament, as the NLD did in 2015 and 2020. A fragmented verdict will make constitutional reform difficult, as no single party will have sufficient numbers, and 25% of legislative seats are reserved for the military.

Some argue that the 2025-26 general elections may herald a reform process similar to that following the 2010 elections. Post the 2010 polls, President Thein Sein, a former military general in civilian clothes, introduced significant political and governance reforms. However, the current military leadership perceives that these reforms laid the foundation for the NLD’s landslide victories in 2015 and 2020. Therefore, it is unlikely that the military will countenance the rise of another reformist military general. Furthermore, many contend that Mr. Thein Sein’s reforms were calibrated and never intended to undermine the military’s dominance within the governance structure.

How has the international community responded?

These elections are neither aimed at reforming the political process nor at ascertaining the will of the people. Instead, they represent a desperate attempt to secure legitimacy for the Tatmadaw in both domestic and international politics. ASEAN has refused to allow Myanmar military leaders to represent their country at its summit meetings. Consequently, the Tatmadaw deputed civilian leaders to these meetings. The military leaders hope that the formation of a government led by personnel in civilian clothing after the elections may help overcome such diplomatic embarrassments.

However, the elections have elicited criticism from some members of the international community. The spokesperson for the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights has stated that the elections may contribute to further polarisation throughout the country. Japan has expressed concern that holding elections without releasing political prisoners could aggravate the situation. Australia and the European Union noted that the elections cannot be termed as free, fair, and inclusive.

On the other hand, China and Russia, which have strong relations with the Tatmadaw, have dispatched election observers to Myanmar.

While the United States has always called for democracy in Myanmar, there are concerns that President Donald Trump may dilute such an approach. A few months ago, the U.S. Treasury Department lifted sanctions on firms and individuals perceived to be close to the Tatmadaw leadership. Despite U.S. authorities noting that the removal constituted the ‘ordinary course of business,’ many Myanmar observers expressed disappointment. There is an apprehension that President Trump may be prioritising access to rare earth minerals in Myanmar.

What lies ahead?

If Myanmar is to experience peace and prosperity, it would require a genuine democratic framework, which is informed by principles of federalism and decentralisation. However, such a political project would require resolving ethnic conflict and carefully navigating contemporary geopolitics.

Sanjay Pulipaka is the Chairperson of the Politeia Research Foundation. The views expressed here are personal.

Published – December 29, 2025 10:28 pm IST

www.thehindu.com (Article Sourced Website)

#Myanmar #voting #conflict #Explained