A new radar satellite, successfully launched Wednesday, will track tiny shifts across almost all of Earth’s land and ice regions, measuring changes as slight as a centimeter.

The satellite is a joint mission between NASA and India’s space agency and has been in the making for more than a decade.

The satellite lifted off from the Satish Dhawan Space Center on India’s southeastern coast. About 20 minutes later, it was released into an orbit that passes close to the North and South poles at 745 kilometers above Earth’s surface.

At the mission control center, the reaction was jubilation. The visitors’ gallery there included a few thousand students, and tens of thousands of people watched online.

“This success is demonstrating teamwork, international teamwork between two space-faring nations,” V. Narayanan, chair of the Indian Space Research Organization, or ISRO, said after the launch.

Casey Swails, NASA’s deputy associate administrator, followed with equally complimentary remarks. “This Earth science mission is one of a kind and really shows the world what our two nations can do,” she said.

The satellite is known as the NASA-ISRO Synthetic Aperture Radar mission, or NISAR. NASA describes it as the most advanced radar system it has ever launched.

Because radar signals pass through clouds, they are ideal for monitoring Earth’s surface. “We can see through day or night, rain or shine,” Paul Siqueira, a professor of electrical and computer engineering at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst, and the ecosystems lead for NISAR, said in an interview.

The NISAR mission on the launch pad at the Satish Dhawan Space Center on India’s southeastern coast

| India Space Research Organization / via The New York Times

Deformations in Earth’s surface could provide early warning of impending natural disasters like volcanic eruptions and landslides. Measurements of ice sheets will reveal which areas are melting and which are growing through accumulated snowfall.

The data could also reveal flooded areas that would otherwise be hidden by bad weather, providing help to rescue teams.

The satellite could have helped after the magnitude 8.8 earthquake off Russia’s Far East coast Wednesday and the subsequent tsunami.

“It’s these types of events that remind us how important the types of measurements that NISAR will be making will be,” Sue Owen, deputy chief scientist at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, said during the launch coverage. “They will help us to be able to forecast where these types of events occur, as well as assess the damage after these earthquakes and tsunamis.”

The first 90 days will be devoted to deploying the spacecraft, including extending a 12-meter-wide gold-plated-mesh antenna reflector, which looks a bit like a giant beach umbrella, testing the instruments and performing initial observations.

The primary mission is scheduled to last three years. If the spacecraft is still operational at that point, it will have enough propellant left to continue for couple more years.

The underlying technology, known as synthetic aperture radar, has been used in space for decades. Sending and receiving multiple radar pulses simulates a much larger antenna, allowing smaller features on the ground to be observed.

A synthetic-aperture radar instrument that flew on NASA’s space shuttle Endeavour in 1994, for example, surveyed a buried “lost city” on the Arabian Peninsula and searched for centuries-old ruins along the Silk Road in western China.

What is different about NISAR is that it will bounce radar waves off almost all of Earth’s surface and will do so repeatedly — twice every 12 days.

That will allow scientists to detect slight changes like slow-motion landslides, and monitor places like Antarctica that are distant and inhospitable.

NISAR “will cover all of Antarctica for the first time,” Eric Rignot, a glaciologist at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in California, said during NASA’s launch coverage. “Conducting these measurements in the Antarctic would be nearly impossible for ground parties, because the continent is so vast.”

The NISAR data will track the motion of glaciers and ice sheets. “Scientists will be able to use this information in climate models to project what sea level would look like in the next few years, in the next decades, in the next century, so we can better protect society and save human lives, too,” Rignot said.

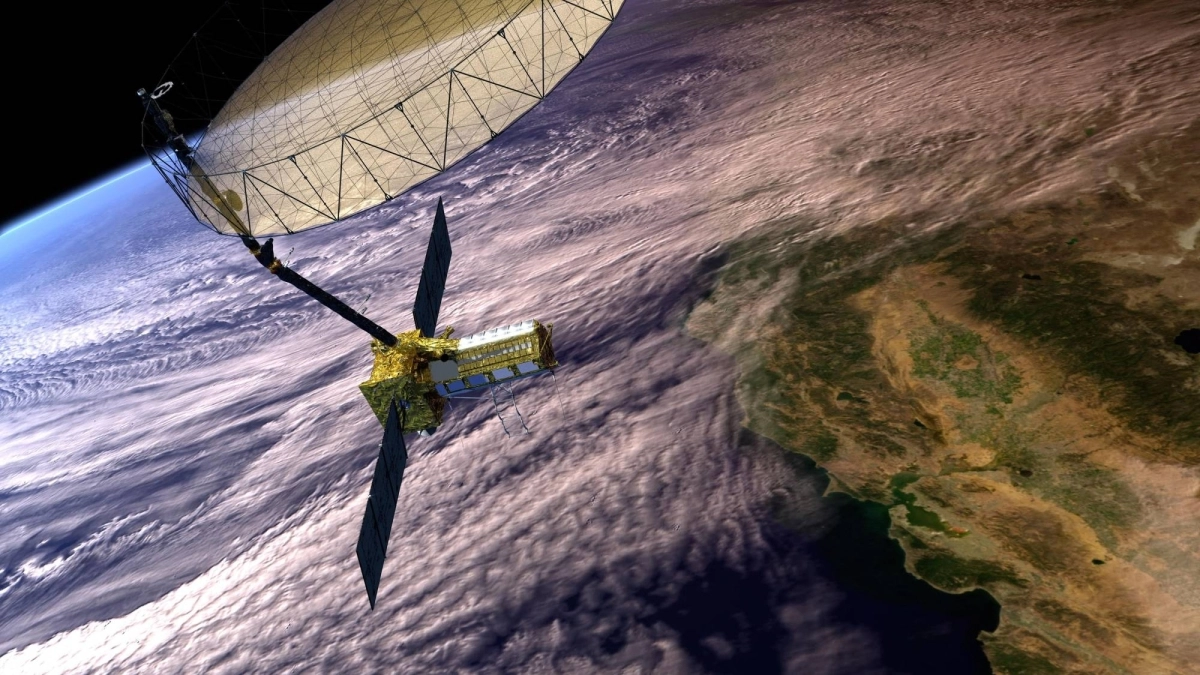

An artist’s concept of the NISAR satellite in Earth orbit

| ISRO/NASA via The New York Times

Siqueira said NISAR could provide practical information closer to home, tracking the growth of crops.

Microwaves bounce off water, so a field of healthy plants will appear brighter. “If a plant is desiccated, it’ll be more radar transparent,” Siqueira said.

The main part of the spacecraft is five meters long and weighs more than two metric tons. Two five-meter-long solar arrays will generate power.

The satellite includes two radar systems. One, built by NASA, will transmit microwaves with a wavelength of 25 centimeters. The other, built by ISRO, transmits 10-centimeter-long microwaves. The two wavelengths will provide details at different size scales. For the study of vegetation, the shorter wavelengths will provide more detail about bushes and shrubs, while the longer wavelengths will provide a clearer picture of taller plants like trees.

The amount of data will be almost overwhelming — terabytes every day. One challenge in designing the mission was figuring out how to send that much data to the ground and then how to process it.

“The sheer volume of data that NISAR is collecting actually pushed NASA into managing data in the cloud,” Gerald Bawden, the mission’s program scientist, said during a news conference Monday.

The idea for a mission like NISAR dates back to a recommendation that appeared in a once-a-decade report by earth scientists that lays out the field’s top priorities for observing Earth from space. NASA looked for an international partner to share the work and cost and finally found one in India in 2014.

NASA’s share of the mission cost $1.2 billion, and ISRO’s contribution was comparable, NASA officials said.

Collaboration with India in space has increased in recent years. An Indian astronaut, Shubhanshu Shukla, flew on the private Axiom-4 mission to the International Space Station last month, spending 18 days there. During a meeting at the White House in February, Narendra Modi, India’s prime minister, and President Donald Trump had called for more collaboration in space exploration. No additional collaborations like NISAR have been announced yet.

This article originally appeared in The New York Times

© 2025 The New York Times Company

www.japantimes.co.jp (Article Sourced Website)

#Earths #surface #shifts #satellite