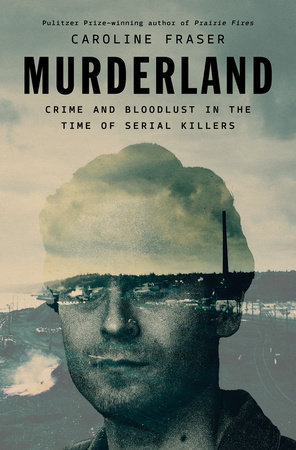

Murderland: Crime and Bloodlust in the Time of Serial Killers, by Caroline Fraser, Penguin Press, 480 pages, $32

The Pacific Northwest produced an appalling roster of serial killers in the 1970s and ’80s, some of whom claimed very large totals of victims. We think immediately of Ted Bundy, but there is also Gary Ridgway, the Green River Killer, with his likely kill count of 50-plus victims; just over the Canadian border, British Columbia produced the serial child murderer Clifford Olson. By some measures, the region is the most prolific in the history of multiple murder.

Observers have often spoken of an “epidemic” with its epicenter at Tacoma, Washington. It is very hard to track serial killings accurately, especially since some styles of murder are more easily detectable in some eras than others, so it is possible that this apparent spike is partly a statistical artifact. But the number of murderers known to be active in this region in this period is undeniably unusually large.

Caroline Fraser’s Murderland explores the crimes of that place and time. It is quirky and sporadically brilliant, bringing together arguments from seemingly unrelated fields of study and combining them in a way that deepens our understanding of mid– and late–20th century America. It’s an impressive book that should be widely read. But it also suffers from omissions and logical flaws.

Fraser integrates well-known true-crime tales into the larger geography of the region, its communication systems, and, above all, its shocking environmental history, which she covers in horrifying detail. Industrial enterprises here spread unacceptable amounts of pollutants into the environment, including some, such as lead, copper, and arsenic, that have disastrous effects on human beings. One respectable (if not fully accepted) theory suggests that the upsurge of general violence in the U.S. that started in the 1960s correlated closely with the quantities of environmental lead produced by gasoline. As Fraser puts it: “More lead, more crime.”

The term “Murderland” thus suggests not just a number of apparent monsters roaming the region, but also lethal conditions imposed wantonly on human populations. Growing up in that toxic environment, Fraser argues, it was only natural that a disproportionate number of children should have developed serious mental and physical anomalies that predisposed them to extreme violence. She presents the murder wave as a by-product of disastrous environmental abuse, to the point where it should almost be seen as a subset of environmental crime. Fraser extends that regional analysis to trace the origins of America’s other very prolific killers, such as the BTK Killer, Dennis Rader, whom she locates in the “lead belt” of Kansas. In that sense, America as a whole became Murderland.

Murderland offers a convincing and immersive sense of growing up in the Pacific Northwest in that era, thanks in part to the book’s autobiographical material. Born in the Seattle suburb of Mercer Island in 1961, Fraser is uncomfortably aware that if matters had developed slightly differently, she might have ended up as a victim of some lethal neighbor such as Bundy. Besides accounts of the notorious wrongdoers, she has many stories of the remarkably numerous less-well-known mass murderers, bomb makers, and arsonists in her community.

And all that is over and above her devastating account of the environmental situation. She devotes much attention to the most egregious environmental offender, the American Smelting and Refining Company, which throughout the period was owned by the Guggenheim family. If her thesis is correct, that esteemed line should be subject to as much public obloquy as was received by Bundy.

For all the book’s virtues, there is much to question in its account of the serial murder phenomenon. Fraser addresses such crimes from the standpoint of understanding how and why any community should generate monsters who wish to kill savagely and repeatedly. But even if we accept her explanations, multiple murder is a complex issue that requires consideration of the cultural and bureaucratic contexts of the time—of the environment defined in a rather different way.

More specifically: The scale and harmfulness of a serial killer’s career actually has very little to do with the degree of his mental disturbance, or of his tendencies to violence. It is a matter of the social setting in which he operates and how he finds his victims.

Imagine two individuals who grow up deeply disturbed and potentially violent, each obsessed with the atrocities he hopes to inflict on potential victims. For the sake of argument, let us assume that both suffer gravely from environmental harms such as lead poisoning. For convenience, I will call the men Bert and Ernie. Bert chooses to turn his rage on authority figures, and he kills a police officer (say) or a high public official. Immediately, that crime earns the full attention of the media and (of course) of police agencies, who spare no effort until the perpetrator is caught and punished. Bert is rapidly arrested and imprisoned, and he never becomes a serial killer.

Ernie, in contrast, chooses to target urban sex workers, and his murders initially attract little public notice. Media and police alike assume that such marginal individuals live in a dangerous and potentially violent environment where life is cheap. Unless the offender inflicts clear signs of criminality, such as mutilations, many of Ernie’s killings will not even be recognized as murder but will be consigned to the category of a drug overdose. In earlier eras, official insouciance was even greater when victims were not white. Not until eight or 10 or 20 young women have perished does some enterprising journalist, perhaps, write a story about the possible connections in the murders and hypothesize a serial killer. Gradually, other media take up the story, and police reluctantly move into action. By the time the offender is apprehended, possibly years later, he has killed dozens and becomes the subject of true-crime documentaries. Perhaps he will earn a reference in a revised edition of Murderland.

If that sketch seems far-fetched, consider the story of Vancouver’s Robert Pickton, who confessed to killing almost 50 women over a period of some years, despite all the efforts of the victims’ friends and relatives to urge authorities to take the crimes seriously. (Many of the victims belonged to First Nations, and most suffered grave issues with substance abuse.) Nobody else cared, and the killings went on. To take another example, only long after the event did it become apparent just how many prolific serial killers had been targeting the black communities of Los Angeles in the 1980s and 1990s, where the deaths of marginal young women were commonly assigned to drug or gang activity. The victims were viewed as disposable, so little thought was given to pressing inquiries further. As in the Pickton case, the offenders got away with murder for decades. If they had chosen Bert’s targets instead, they never would have killed enough victims to graduate to serial murder status.

Any study of that serial murder wave of the 1970s and 1980s amply confirms the decisive role of official attitudes, and of which victims the criminal chooses. Yes, the horrible environmental setting produced by the smelting might well have created a wave of monsters, such as Pickton or Bundy, who perhaps could not have been prevented from killing at least once. But such people could not have killed prolifically without the social, demographic, and sexual revolutions of the age, which allowed them to be in intimate conditions with multiple partners whose deaths or disappearances would not attract much official concern. Meanwhile, the sprawling drug subculture drove a large number of people into red-light neighborhoods where they depended on selling sex to survive. As the baby boom generation entered adulthood, many young people were open to taking risks with strangers in ways that would have seemed perilous to earlier eras—and authorities saw little percentage in attempting a crackdown on random promiscuity, whether straight or gay.

So the potential victim population swelled for a while, offering a wonderful temptation to the depraved and violent. Together, those potent factors might well have conspired to create a serial murder “epidemic” even if nobody had ever thought to put a smelter in the area. Who can tell?

Any realistic attempt at understanding America’s “Murderland” must of necessity foreground the culture and conditions of the societies that the monsters prey on. Murderland makes no sense without considering Victimland.

reason.com (Article Sourced Website)

#caused #serial #killing #spike #1970s #80s