On Friday, María Daniela learned that her younger brother, Neri Alvarado Borges, and more than 200 other Venezuelans sent by the Trump administration to El Salvador were being released after spending more than four months in an infamous prison. “Now it’s done,” María Daniela said in a call from Venezuela. “Now we can say we are done with this nightmare.”

Alvarado’s case, which Mother Jones reported on in March, was emblematic of the cruelty of the Trump administration’s decision to send hundreds of Venezuelans to Salvadoran President Nayib Bukele’s Centro de Confinamiento del Terrorismo (CECOT) prison. Like many others, Alvarado, who worked as a baker in the Dallas area, appears to have been targeted simply because he was a Venezuelan man with tattoos. It did not matter that his most prominent tattoo was an autism awareness ribbon adorned with the name of his teenage brother.

“We got a beating for breakfast. We got a beating for lunch. We got a beating for dinner.”

The Venezuelans were released as part of a prisoner swap deal including 10 Americans. (The Venezuelan government has been reported to imprison foreign nationals to gain diplomatic leverage.) The exchange comes after a previous deal being negotiated fell through, and despite the Trump administration’s insistence in court and in public statements that it did not have the power to compel El Salvador to return the removed migrants to the United States. (Court records show that Bukele’s government told the United Nations the men were under the authority of the United States, contradicting the White House’s claims.)

A relative shared a video from Venezuelan broadcaster teleSUR featuring his brother, Arturo Suárez, on the plane after it landed near Caracas. “We spent four months without any contact with the outside world,” Suárez said. “We were kidnapped.” He went on to say: “We got a beating for breakfast. We got a beating for lunch. We got a beating for dinner.”

Family members of some of the Venezuelan men held at CECOT told Mother Jones they were relieved, but still heartbroken over what they consider a wrongful detention. On Friday, families had been instructed by the Maduro government’s office to go to the airport near Caracas to reunite with their relatives.

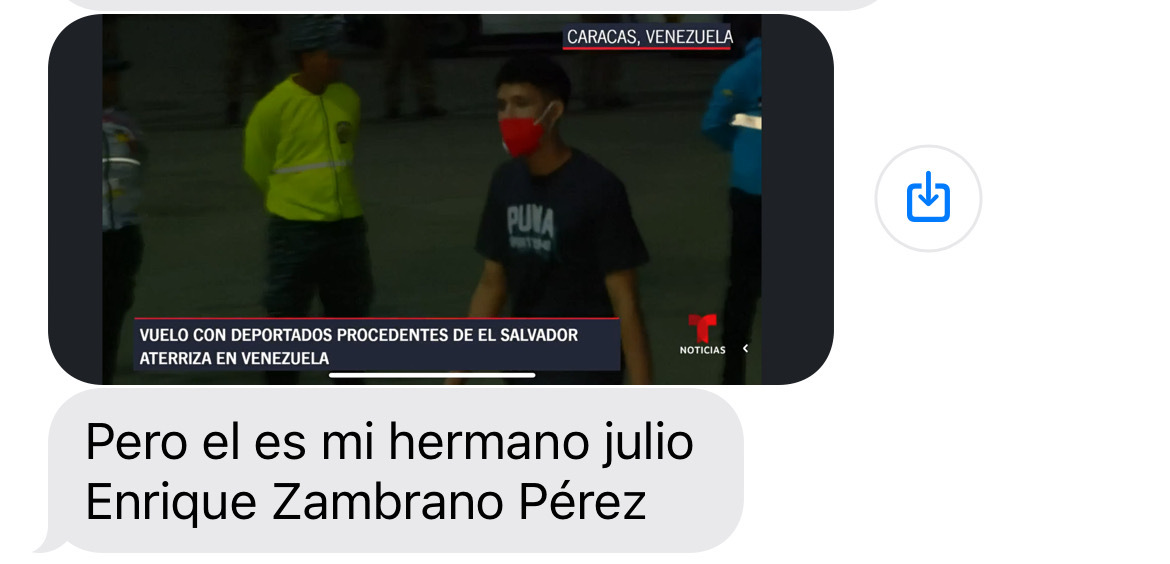

Anaurys Orlimar, the sister of one of the men, Julio Zambrano, said that earlier on Friday their mother was contacted with “good news” and told to travel from Maracay to the Caracas area. Her son, Julio, had been seeking asylum in the United States. The father of two was detained in January during a routine check-in with Immigration and Customs Enforcement. His then-pregnant wife, Luz, said an officer told her they suspected Zambrano—who has two tattoos of a crown with his name and a rose—was part of a gang, which his relatives dispute.

“We are all happy and eager to see him,” Orlimar, who lives in North Carolina, said. “We didn’t expect this. We didn’t know anything. What we all did was cry with emotion knowing that my brother is going to return, that he’s going to get out of this.” Later, she recognized her brother, wearing a red face mask and a Puma t-shirt, in Telemundo’s live coverage of the flight’s arrival.

Mariangi Sierra, sister of Anyelo Sierra Cano, said in a message she was feeling “emotional, happy, truly something inexplicable.”

For some relatives, the news of the men’s return to Venezuela evoked more mixed feelings. Maria Quevedo, the mother of Eddie Adolfo Hurtado Quevedo, told Mother Jones she was feeling relieved but still scared. “Happy because God gave me the gift of seeing my son free on my birthday,” she said. “Scared because my son is going to Venezuela, where he was threatened by the [paramilitary group] colectivos.”

Dozens of Venezuelans sent to CECOT had pending asylum applications in US immigration courts when they were removed. In some instances, their cases have been dismissed by immigration judges. They could now be vulnerable to potential harm and persecution back in Venezuela.

“The bitterness is still there,” said a friend of one of the men sent to CECOT about the release. “The anger about what happened to him is still there.”

The men released today had been held at the maximum security prison since March, when the Trump administration sent more than 230 Venezuelans accused of being gang members to El Salvador. At least 130 of them were removed without due process under the Alien Enemies Act of 1798, a wartime power that Trump invoked for only the fourth time in US history. Investigations by Mother Jones and other publications revealed that many of the men had no connection to Tren de Aragua and appeared to have been targeted over benign tattoos—like Alvarado’s autism awareness ribbon. Most of them had no criminal history in the United States, according to ProPublica and Bloomberg. (The administration has repeatedly refused to provide evidence to support its assertion of gang affiliation.)

In a statement on Friday, the Venezuelan government said it had secured the release of 252 Venezuelan nationals who “remained kidnapped and subjected to forced disappearance in a concentration camp” in El Salvador. “Venezuela has paid a high price,” the statement continued, to free the men as part of an agreement with US government authorities. The deal also reportedly included the return to Venezuela of seven migrant children who had stayed behind in the United States after their parents were deported, according to the country’s Interior Minister Diosdado Cabello.

When María Daniela, Alvarado’s sister, spoke to Mother Jones on Friday, she and her family were about to make the roughly four-hour drive from their home to the Caracas area. Once there, they would finally be reunited with Alvarado, the brother and son they had no contact with for more than four months.

Juan Enrique Hernández, a US citizen who came to the United States from Venezuela nearly three decades ago, was Alvarado’s boss at the bakery in the Dallas area. The two became good friends, and Hernández visited Alvarado in detention in Texas multiple times following his February arrest.

Hernández said he did everything in his power to get Alvarado out. “I went to many lawyers here and none wanted to take the case,” he explained. “They said they didn’t have jurisdiction.”

“I have mixed feelings. I’m happy on one hand,” Hernández said on Friday about Alvardo’s imminent release. “But the bitterness is still there. The anger about what happened to him is still there.”

www.motherjones.com (Article Sourced Website)

#kidnapped