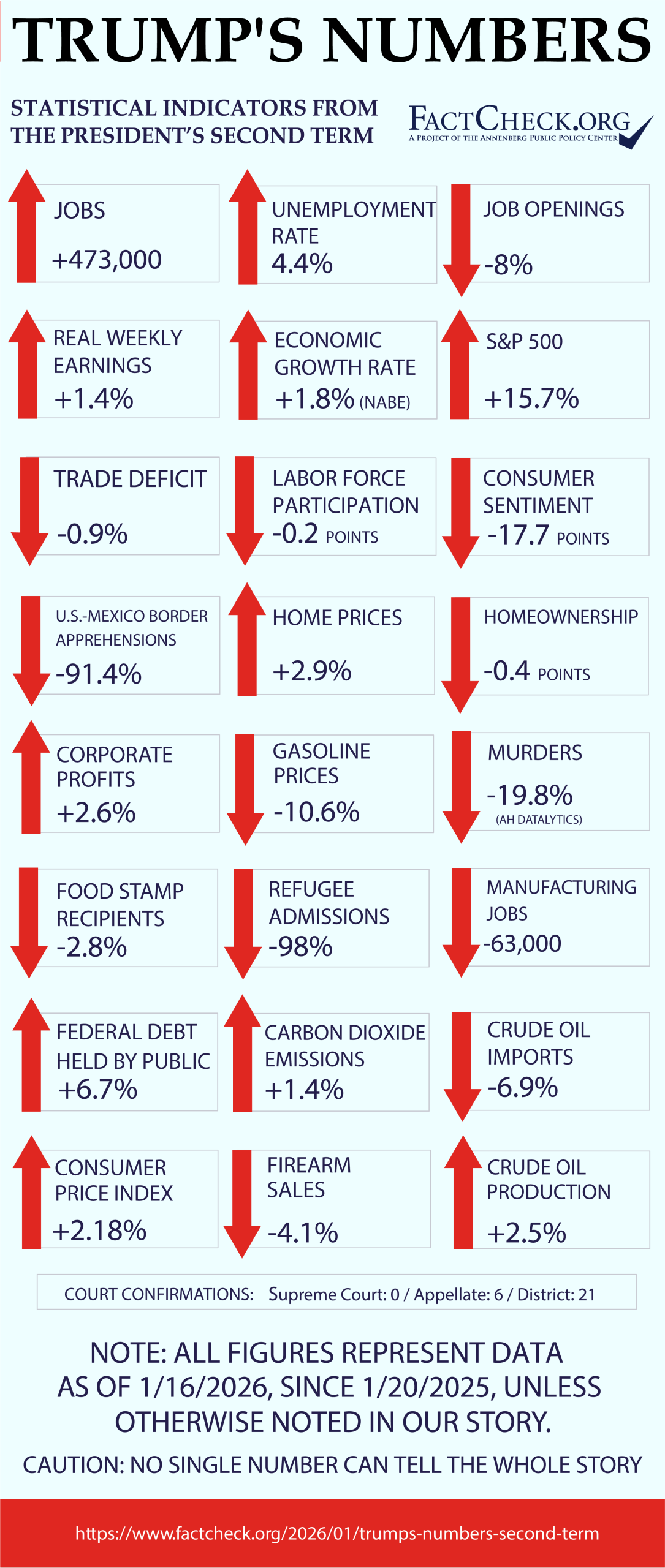

Summary

Since President Donald Trump returned to the White House:

- Job growth slowed, and the unemployment rate crept upward. Job-seekers now outnumber job openings.

- Price increases slowed according to the most commonly watched number. But they worsened according to the measure preferred by the Federal Reserve.

- Paychecks grew faster than inflation. Real weekly earnings of private-sector workers rose 1.4%.

- Economists estimate the economy grew 1.8%.

- Consumer sentiment declined.

- The number of apprehensions at the U.S. border with Mexico decreased 91.4%, while refugee admissions declined 98%.

- The international trade deficit decreased only slightly, by 0.9%.

- The stock market continued to set new records.

- The number of people receiving federal food assistance went down by about 1.2 million.

- Oil production went up 2.5%, while oil imports dropped 6.9%. Carbon emissions increased slightly.

- The number of murders nationwide continued to decline, a trend that began in 2022.

- The federal debt held by the public rose about 6.7%.

Analysis

Now that Trump has been back in office for one year, we’re publishing our first “Trump’s Numbers” article of his second term. That’s the schedule we have followed for these reports, which we launched in 2012. We wait a year when a new president is inaugurated to allow for the accumulation of some data on most of these metrics.

Going forward, we’ll provide quarterly updates throughout Trump’s term, as we did for his predecessors, and we’ll be able to include statistics that are missing from this report — household income, poverty and health insurance — once the data are released.

In a Jan. 13 speech, Trump himself cited “the numbers” for his economic record, making a healthy, and incorrect, use of superlatives. “By almost every metric, we have quickly gone from the worst numbers on record to the best and strongest numbers,” he said. “Just based on the numbers.”

While that’s clearly not accurate for “almost every metric,” the idea behind these articles isn’t to fact-check specific claims; rather, we simply provide the numbers. They may be expected or surprising, good or bad, depending on one’s point of view. We leave those opinions to readers, and we make no judgments as to how much credit or blame a president deserves for these measures.

Jobs and Unemployment

Job growth slowed and unemployment crept up during Trump’s second term. The number of unemployed now exceeds the number of job openings.

Employment — Employment continued growing during Trump’s first 11 months in office, but much more slowly than it had in the previous 11 months.

The most recent figures from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics show an increase of 473,000 in total nonfarm employment between January and December 2025. That’s barely more than one-quarter of the 1,782,000 jobs added between February 2024 and January 2025, when Trump began his current term.

(A note of caution: BLS has announced it will revise its monthly job figures substantially downward for March because its annual “benchmarking” study indicated its monthly survey had overcounted the number of jobs that month by 911,000. Updated figures going back to March 2024 are scheduled to be released in February along with the regular monthly employment report.)

Much of the sluggishness under Trump is due to the president’s deliberate slashing of the federal workforce. Federal government employment has fallen by 277,000, or 9.2%, since he took office.

Looking only at the private sector — excluding federal, state and local government workers — 654,000 jobs were added during Trump’s term so far. But that’s still less than half the 1,414,000 added in the preceding 11 months.

Back in August, Trump reacted to disappointing job-growth figures by calling them “rigged” and “phony” even though we found no evidence of that and the White House offered none. Trump fired BLS Commissioner Erika McEntarfer and nominated as her replacement E.J. Antoni, an economist at the conservative Heritage Foundation. Trump withdrew that nomination amid much criticism at the end of September and has yet to name a permanent replacement.

Meanwhile BLS reported a gain of only 50,000 jobs in the month of December. That’s even lower than the initial report of a 73,000 gain in July that prompted Trump to fire the BLS chief. The July gain has since been revised downward to 72,000.

Manufacturing Jobs — The economy continued to lose manufacturing jobs. During Trump’s first 11 months the loss was 63,000. That followed a loss of 98,000 in the preceding 11 months.

Labor Force Participation — The labor force participation rate declined a bit in Trump’s second term, dropping from 62.6% to 62.4%.

The rate is the portion of the population over age 16 that is working or seeking work. It generally has been in a long decline as the population ages and people retire.

Unemployment — The unemployment rate has remained well below the historical norm under Trump, but has gone up slightly since he took office. It was 4.0% in January 2025, and most recently was 4.4% in December.

The median rate for all months since 1948 is 5.5%.

Job Openings — The number of people officially listed as unemployed rose by 638,000 during Trump’s first 11 months, while the number of job openings declined by 616,000. There are now 7.5 million unemployed and seeking work, but only 7.1 million openings. When Trump took office, job opportunities outnumbered job-seekers.

Wages and Inflation

CPI — Trump campaigned on a promise to reduce inflation, and since he took office it has slowed little. Or maybe not. By one important measure it has worsened.

In the 12 months before Trump took office the Consumer Price Index, the most commonly cited measure of inflation, rose 3.0%. And in the most recent BLS report, the 12-month increase was 2.7%.

Over Trump’s first 11 months in office, the CPI went up 2.18%.

One particularly bright spot: The often volatile price of gasoline has eased. The national average price for regular gasoline at the pump was $3.11 the week Trump was sworn in for the second time, and had dropped to $2.78 by the week ending Jan. 12, according to the Energy Information Administration.

Inflation was much worse in 2022, when the 12-month CPI increase spiked at 9.1% in June. That was the largest 12-month increase in over 40 years. But inflation had slowed markedly by the time Trump came in.

Still, inflation remains higher than the Federal Reserve would like, and it’s going in the wrong direction as measured by the Fed’s preferred metric, the Personal Consumption Expenditures Index, compiled by the Bureau of Economic Analysis.

The central bank’s target is a 2% annual increase in the PCE. When Trump took office, the 12-month increase in the PCE was 2.5%. But the most recent report put the 12-month increase at 2.8%.

That was for the period ending in September. Not only do the PCE figures take longer to gather than the CPI, they have been delayed by the recent government shutdown. The next PCE release is now scheduled for Jan. 22 and will cover both October and November.

Wages — Wage increases accelerated under Trump, even adjusted for inflation.

The average weekly earnings of all private-sector workers, adjusted for inflation, rose 1.4% during Trump’s first 11 months. They were rising when he took office, but had only gone up 0.5% in the preceding 11 months.

Those figures include professionals, executives and supervisory employees, whose pay is normally higher. But rank-and-file wage earners are seeing gains just as rapid as those of their bosses. For private-sector production and nonsupervisory employees, real average earnings also rose 1.4% under Trump, after a 1.0% rise in the preceding period.

Economic Growth

After a weak first quarter, the economy showed surprising resilience in Trump’s first year back in office – largely on the strength of substantial artificial intelligence investments and household spending.

Although the first official annual estimate from the Bureau of Economic Analysis isn’t due to be released until Feb. 20, BEA data available so far show that real gross domestic product declined at an annual rate of 0.6% in the first three months of 2025 but then grew by 3.8% in the second quarter and 4.3% in the third quarter.

The reported third-quarter growth was the largest in two years, when the economy expanded at an annual rate of 4.7%. Fourth quarter growth, which also won’t be released until Feb. 20, may be even higher. As of Jan. 14, the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta’s GDPNow model was projecting growth of 5.3%.

“This strong growth came despite the adverse trade and immigration shocks the economy has absorbed over the past year,” resulting in a “soft labor market,” Joseph Brusuelas, chief economist at RSM, wrote in December after the third-quarter figures were released. “That interplay — a surging economy and a soft labor market — is likely to be the major economic narrative next year.”

Brusuelas described the economy as a “resilient beast.” He attributed the third-quarter growth to “[h]ousehold consumption driven by higher-income consumers and AI-related investment,” which he wrote “accounted for just under 70% of total growth during the [third] quarter.”

For the full year, Federal Reserve Board members and bank presidents expect growth to come in at between 1.5% and 2%, according to estimates released Dec. 10. Their median projection was 1.7%. Similarly, economists surveyed in October by the National Association for Business Economics estimated 1.8% growth in 2025.

Consumer Sentiment

When Trump took office, consumers surveyed by the University of Michigan expressed concern about unemployment and inflation and uncertainty about the potential impact of Trump’s economic agenda.

“Concerns over the future trajectory of inflation were visible throughout the interviews and were tied to beliefs about anticipated policies like tariffs,” Joanne W. Hsu, director of the Surveys of Consumers, said in a press release last January, adding that “consumers of all political leanings will continue to refine their views as Trump’s policies are clarified and implemented.”

A year ago, the university’s survey showed that the consumer sentiment was 71.7. Since then, consumer confidence has precipitously declined in subsequent surveys and remains stubbornly low.

The university’s preliminary Index of Consumer Sentiment for January was 54 – 17.7 points lower than it was when Trump took office. By contrast, consumer sentiment never dropped below 71.8 in Trump’s first term, despite the economic turmoil caused by the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic in early 2020.

Although those surveyed perceived some “modest improvement” in the economy in the last two months, consumer sentiment “remains nearly 25% below last January’s reading,” Hsu said. Consumers “continue to be focused primarily on kitchen table issues, like high prices and softening labor markets.”

In its most recent Consumer Confidence Survey, the Conference Board — a research organization with more than 2,000 member companies — also reported that consumer confidence declined for the fifth straight month in December.

“Despite an upward revision in November related to the end of the [government] shutdown, consumer confidence fell again in December and remained well below this year’s January peak,” Dana M. Peterson, chief economist of the Conference Board, said in a Dec. 23 press release.

Home Prices & Homeownership

Homeownership — Homeownership rates have declined slightly since Trump became president.

The homeownership rate, which the Census Bureau measures as the percentage of “occupied housing units that are owner-occupied,” was 65.3% in the third quarter of 2025 — 0.4 points below the 65.7% rate during Biden’s last quarter in office.

Although mortgage rates eased in 2025, the homeownership rate in the third quarter “remained below last year’s pace because of ongoing affordability pressures,” according to Realtor.com.

“Persistent affordability challenges and a shortage of reasonably priced homes have kept the rate from rising more meaningfully, though recent inventory gains, softer prices, and easing mortgage rates appear to be helping some previously sidelined households enter the market,” Realtor.com Senior Economic Research Analyst Hannah Jones said in a Dec. 12 article on the company’s website.

The highest homeownership rate on record was 69.2% in 2004, when George W. Bush was president. But millions of Americans lost their homes during the Great Recession, a financial crisis triggered by a housing market crash.

“Following record-high homeownership rates before the 2008 housing and financial crisis, homeownership rates have remained relatively static at the current rate of 65 percent,” HUD’s policy and research arm wrote in a July report on the history of homeownership in the U.S.

Home Prices — Home prices, which soared to new highs under Biden, slowed in Trump’s first year, as mortgage rates continued to fall.

The national median price of an existing, single-family home sold in December was $409,500, according to the National Association of Realtors. That was 2.9% higher than it was in January, when Biden left office.

Looked at another way: The median sales price in December was only 0.24% higher year-over-year.

“2025 was another tough year for homebuyers, marked by record-high home prices and historically low home sales,” NAR Chief Economist Lawrence Yun said in a press release. “However, in the fourth quarter, conditions began improving, with lower mortgage rates and slower home price growth.”

The Federal Reserve lowered short-term interest rates three times in 2024. After a pause, the Fed cut rates three more times in 2025 – lowering rates last year by a full percentage point since September. While that’s not directly tied to mortgage rates, it can affect how banks set their loan rates.

As of Jan. 8, the average mortgage rate on a 30-year fixed rate mortgage was 6.16% — down from 6.96% for the week ending Jan. 23, 2025, according to Freddie Mac. Trump took office on Jan. 20, 2025.

Immigration

In his first year in office, Trump has followed through on his signature campaign promise to — as he puts it — “close the border,” with numerous executive actions that have dramatically reshaped immigration policy and enforcement.

“The border is totally secure,” Trump told reporters on Jan. 11.

The number of apprehensions at the U.S. border with Mexico decreased 91.4% during Trump’s first full 11 months in office, compared with the same period in 2024, according to the most recent figures released by U.S. Customs and Border Protection. The monthly average (7,255) was at a low not seen since the early 1960s.

Calculating the change in border apprehensions is the method we’ve used as a proxy to measure illegal border crossings for our Numbers stories going back to President Barack Obama. But in Trump’s case, that dramatic drop tells only part of the story of the sweeping immigration policy changes that the Migration Policy Institute describes as “unprecedented in their breadth and reach.”

“While some efforts have stalled or not yet met the White House’s lofty goals, the administration has dramatically reshaped the machinery of government to target unauthorized immigrants in the country, deter unauthorized border arrivals, make the status of many legally resident immigrants more tenuous, and impose obstacles for lawful entry of large swaths of international travelers and would-be immigrants,” MPI’s Muzaffar Chishti, Kathleen Bush-Joseph and Colleen Putzel-Kavanaugh wrote in their Jan. 13 article, “Unleashing Power in New Ways: Immigration in the First Year of Trump 2.0.” The “net change,” the authors wrote, “has been dizzying in its scope and speed.”

The Trump administration has “dismantled longstanding norms,” the authors wrote, invoking “archaic statutes,” enlisting “support from state and local law enforcement as well as federal agencies that historically had no immigration enforcement role,” and pressuring “foreign governments to receive deportees,” the MPI report stated. “Perhaps most visibly, it militarized immigration enforcement.”

Trump has achieved his policy mostly through executive actions, rather than with legislative help, something he has boasted about repeatedly.

“Remember Biden, he said I have to get approval from Congress,” Trump said in a speech in Detroit on Jan. 13. “Had nothing to do with Congress, had to do with respect.”

In one of his first actions upon taking office in January 2025, Trump issued a proclamation that “the current situation at the southern border qualifies as an invasion under Article IV, Section 4 of the Constitution of the United States.” He mostly blocked migrants’ ability to request asylum. He canceled humanitarian parole programs that the Biden administration extended to Cuba, Haiti, Nicaragua and Venezuela. And he reinstated the “Remain in Mexico” policy, so that asylum seekers were sent to Mexico to await their court appearances in the U.S.

In December, Trump paused all asylum decisions at U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services. And on Jan. 14, the president indefinitely paused the processing of immigrant visas for 75 nations, including Afghanistan, Brazil, Egypt, Iran, Nigeria, Russia, Thailand, Somalia and Yemen. He had previously issued a full or partial ban on travel from 39 countries.

MPI estimated that in the first year of his second term, Trump has taken more than 500 actions on immigration including 38 executive orders and “hundreds of other actions via presidential proclamations and policy guidance.” That’s more actions than in all four years of Trump’s first term, MPI said.

But Congress has provided some help. In July, Republicans passed the One Big Beautiful Bill Act, which included more than $170 billion to ramp up immigration enforcement, detention and deportation.

Increasingly, the administration has turned its attention to interior enforcement. According to MPI, “U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) arrests have more than quadrupled since Trump took office, while average daily detention has doubled.”

In December, the Department of Homeland Security reported that its enforcement operations have resulted in more than 622,000 deportations since January 2025 (short of the stated goal of at least 1 million per year). And, DHS said, another “1.9 million illegal aliens have voluntarily self-deported,” some of whom were lured by government incentives — a free flight home and $1,000. MPI said the Trump administration hasn’t provided any data to back up that self-deportation claim.

A New York Times analysis of federal data disputed the administration’s figures, with its Jan. 17 analysis, covering Trump’s first year, estimating the number of deportations at 540,000, including 230,000 people who were detained inside the country, 270,000 deported at the border and 40,000 who signed up for the government incentives to self-deport. The Times speculated that the administration’s 622,000 figure “likely includes all repatriations carried out by various homeland security subagencies,” such as ship crews that are barred from disembarking.

Both the Times and MPI noted that DHS hasn’t released detailed, public reports on these statistics, as it has in the past.

In any case, the Times noted the number of deportations lagged the number in Biden’s last two years in office: 590,000 total deportations in 2023 and 650,000 in 2024, when border apprehensions were much higher than they are now. The number of people Trump has deported from inside the country, 230,000, is far higher than the 50,000 deported from inside the country in 2024.

Refugees

In his first term, Trump sharply reduced refugee admissions. But now they have nearly stopped entirely.

As we wrote last year, Trump signed an executive order on his first day back in office that called for a “realignment” of the U.S. Refugee Admissions Program, including an indefinite suspension of all admissions until the program “aligns with the interests of the United States.”

There have been few exceptions to the new refugee policy – notably for refugees from South Africa’s white minority Afrikaner ethnic group. In making an exception for Afrikaners, Trump claimed there was “a genocide that’s taking place” against white farmers in the country – which, as we wrote, distorts the facts.

Beginning in February, the U.S. has admitted only 1,226 refugees in Trump’s first full 11 months in office – including 1,059 refugees from South Africa, according to State Department data.

By contrast, the U.S. admitted 70,033 during the same 11-month period, from February 2024 through December 2024, under Biden. That’s a staggering 98% decline.

For fiscal year 2026, which began Oct. 1, 2025, Trump placed a cap of 7,500 on refugee admissions – which is far fewer than the 125,000 cap Biden instituted for fiscal year 2025. It’s also much less than the 45,000 cap that Trump placed on refugees in fiscal year 2018, which was his first full fiscal year as president during his first term.

Other than refugees from South Africa, Trump was forced by a court ruling to admit some refugees who had plans to resettle in the U.S. when he suspended the program.

As we wrote, an appeals court ruled (in a clarifying opinion issued April 21) that refugees who had an “approved refugee application” and “had arranged and confirmable travel plans” on or before Trump’s Jan. 20 executive order can enter the country. About 160 refugees were affected by that decision, a spokesman for the International Refugee Assistance Project told us for an article in September.

Most of the non-South Africans admitted last year came from Afghanistan. The U.S. admitted 100 Afghan refugees in the past 11 months, the State Department data show.

In addition to suspending the refugee program, Trump more recently has threatened to deport refugees who settled in Minnesota, citing an ongoing fraud investigation in that city.

In a Jan. 9 statement, the Department of Homeland Security said it is “reexamining thousands of refugee cases through new background checks and intensive verification of refugee claims,” beginning with “Minnesota’s 5,600 refugees who have not yet been given lawful permanent resident status (Green Cards).”

Trade

The international trade deficit, which Trump criticized for reaching record levels under Biden, decreased only slightly in the months since Trump took office for his second term.

Through his first full nine months in office, the U.S. imported $654 billion more in goods and services than it exported, according to the most recent data from the Bureau of Economic Analysis. That’s about 0.9% less than the $659.7 billion gap between U.S. imports and exports during the same period in 2024.

The full impact of Trump’s new tariff policies on the trade imbalance is still to be determined. The New York Times noted that “because of a surge in imports earlier this year,” to avoid import tariffs that later went into effect, “the overall trade deficit from January to October was still up 7.7 percent from the previous year.”

Also, when the goods and services trade deficit for the month of October went down 60% year-over-year to $29.4 billion, the lowest monthly total since June 2009, the Times said that some economists attributed the decrease to “temporary fluctuations in trade in certain products, like gold and pharmaceuticals.”

Mark Zandi, chief economist at Moody’s Analytics, told the newspaper: “Cutting through the noise and getting to the underlying signal in the data, it suggests to me that the deficit is as large as its ever been.”

Corporate Profits

Corporate profits set records each year under Biden, but dipped in the first quarter under Trump before rebounding slightly in the second quarter and recovering fully in the third quarter.

The Bureau of Economic Analysis reported that after-tax corporate profits at an annual rate were $3.59 trillion in the third quarter of 2025 – about $91 billion, or 2.6%, higher than the full-year figure for 2024.

The fourth quarter and annual figures for last year won’t be released until March, so it is still unclear if after-tax corporate profits for the full year will be up or down.

Under Biden, the annual average growth was 31% in 2021, 3.8% in 2022, 7.8% in 2023 and 7.9% in 2024, according to BEA data.

Stock Market

The stock market, which set records during Biden’s presidency, reached new heights again under Trump.

The S&P 500, which is made up of 500 large-cap companies, closed at 15.7% higher on Jan. 16 than it was three days before Trump’s inauguration in January 2025.

The Dow Jones Industrial Average, made up of 30 large corporations, was up 13.5% over that same period.

And the Nasdaq composite index, comprising more than 3,000 companies, many in the technology sector, surged by almost 19.8% in that time frame.

These gains followed ample market increases during the Biden administration, when the S&P rose 57.8%, the Dow Jones went up 40.6%, and the Nasdaq increased by almost half.

Food Stamps

After a slight increase in enrollment during Biden’s presidency, the latest data from the Department of Agriculture show that under Trump fewer people are accessing benefits from the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, formerly known as food stamps.

About 41.6 million people were receiving federal food assistance in September, according to preliminary USDA figures published last month. The number has gone down by about 1.2 million participants, or 2.8%, since Trump took office.

The number of individuals benefiting from SNAP is expected to decline further because of the Republicans’ One Big Beautiful Bill Act, which changed eligibility requirements for SNAP and is estimated to reduce federal spending on the program. For example, the law extends work requirements to include “able-bodied adults without dependents” aged 55 to 64, who were previously exempt.

In August, the Congressional Budget Office said that provisions in the law “will reduce participation in SNAP by roughly 2.4 million people in an average month over the 2025-2034 period.”

Crime

We won’t have annual 2025 crime data from the FBI until the fall. But other reports on part of the year show violent crime has continued to drop, a trend that began in 2022 after a spike in crime, particularly murders, in 2020.

AH Datalytics, an independent criminal justice data analysis group, produces a Real-Time Crime Index, an aggregation of crime data collected from 570 law enforcement agencies. That index shows a 19.8% decline in the number of murders for January to October 2025 compared with the same period in 2024. Longer term, the index shows the number of murders jumped in 2020, during the COVID-19 pandemic, then leveled off and has been dropping since 2022.

The latest report from the Major Cities Chiefs Association, which compares Jan. 1 to Sept. 30, 2025, to the same period in the prior year, similarly found a 19.1% decline in the number of murders for 67 law enforcement agencies. The number of rapes, robberies and aggravated assaults also went down, with the latter decreasing by 10%.

A midyear 2025 report by the Council on Criminal Justice on 42 cities, which consistently published data since 2019, found the same trend, with crime levels now mostly below pre-pandemic levels. “Examining trends over a longer timeframe, violent crimes are below levels seen in the first half of 2019, the year prior to the onset of the COVID pandemic and racial justice protests of 2020,” the CCJ report said. It noted, though, that the drop in murders has been concentrated in a few cities.

“Much of the decline in the national homicide rate, which began in late 2022, has been driven by large drops in a few sample cities with high homicide levels, such as Baltimore and St. Louis,” CCJ said in a press release about its findings. “The most recent data show that all of the sample cities are now below the general peak of 2020 to 2021, but more than 60% continue to experience homicide levels above pre-2020 rates.”

Gun Sales

After reaching a record high in 2020, estimated gun sales declined every year that Biden was president. That downward trend continued during Trump’s first year back in office.

The government doesn’t collect data on gun sales. But the National Shooting Sports Foundation — the gun industry’s trade group — estimates gun sales by tracking the number of background checks for firearm sales based on the FBI’s National Instant Criminal Background Check System. The NSSF-adjusted figures exclude background checks unrelated to sales, such as those required for concealed-carry permits.

According to NSSF, the number of background checks for gun purchases in 2025 was roughly 14.6 million – down 4.1% from about 15.2 million in 2024. But the 2025 total was still higher than the almost 13.2 million estimated sales in 2019, before the pandemic.

Meanwhile, the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives has yet to publish its annual manufacturing figures, so we don’t know whether firearm production, specifically of handguns, increased or decreased in 2025.

Debt and Deficits

Trump’s campaign pledge that “we’re going to actually start paying off debt” hasn’t happened yet. The publicly held debt increased by about one-third on Biden’s watch and continued to rise during the first year of Trump’s second term.

As of Jan. 14, the debt held by the public, which excludes money the federal government owes to itself, was almost $30.8 trillion – up about 6.7% from more than $28.8 trillion on Jan. 17, 2025, three days before he took office.

Another annual deficit – close to $1.8 trillion in the fiscal year that ended Sept. 30 – was a key factor. It was the fourth highest fiscal deficit of all time (behind FY 2020, FY 2021 and FY 2024) and the sixth consecutive budget gap of more than $1 trillion.

Trump’s new Department of Government Efficiency had promised to cut federal spending by at least $1 trillion, a goal it did not achieve. Instead, federal spending went up a bit in fiscal 2025.

And, so far, the U.S. appears headed for another debt-increasing deficit in FY 2026 – although perhaps a smaller one. From October through December, the first quarter of the current fiscal cycle, the CBO said that federal outlays exceeded revenues by $601 billion. That’s about $110 billion less than the deficit in the same quarter of fiscal 2025.

Oil Production and Imports

Trump campaigned on a promise that the U.S. would “drill, baby, drill” during a second Trump term, and on his first day back in office, he signed an executive order with a stated goal of “unleashing American energy.”

As of October, U.S. crude oil production had increased to an average of 13.6 million barrels per day in Trump’s first full nine months in the White House, according to the most recent data from the U.S. Energy Information Administration. That’s up almost 2.5% from the same nine-month period in 2024.

Before Trump was inaugurated, and before any of his policies were in place, the EIA had already projected in its monthly Short-Term Energy Outlook that average daily production would increase to a record 13.5 million barrels a day in 2025.

U.S. crude oil imports are trending in the opposite direction.

Imports were down to an average of about 6.1 million barrels per day during Trump’s first full nine months — a decrease of 6.9% from nearly 6.6 million barrels per day during the comparable period a year earlier. During the Biden years, average imports increased annually.

Carbon Emissions

EIA data also show a small increase in U.S. carbon dioxide emissions from energy consumption under Trump

There were approaching 3.2 billion metric tons of emissions from the consumption of coal, natural gas and various petroleum products in his first full eight months in office. That was roughly 1.4% more than the over 3.1 billion metric tons that were emitted from consuming those energy sources during the same stretch in 2024.

In early January 2025, the EIA projected that CO2 emissions would increase slightly in 2025, but remain in the ballpark of 4.8 billion metric tons emitted in 2024. The agency said it expected emissions growth due to the increased consumption of petroleum products across multiple sectors, particularly the use of diesel fuel and jet fuel.

Emissions had declined in 2023 and 2024 after increasing in Biden’s first two years as president.

Health Insurance

We don’t yet have data on how health insurance coverage has changed so far under Trump’s second term. Typically, the National Health Interview Survey has released quarterly preliminary reports on the insurance status of Americans. But the NHIS’ website now says that as of 2025, the data will only be released biannually.

The latest report, posted in June 2025, covers calendar year 2024. The NHIS is a project of the National Center for Health Statistics at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

A report on estimates from the survey for January to June 2025 is scheduled to be released on Jan. 30.

The One Big Beautiful Bill Act, which Trump signed into law in July, is expected to prompt a rise in the number of people who lack health insurance, starting next year. The nonpartisan Congressional Budget Office estimated the uninsured would increase by 10 million people over 10 years, with most of the increase due to the law’s changes to Medicaid. For 2026, the rise was estimated at 1.3 million people. (See the link to estimated changes in people without health insurance.)

In 2024, the last year of Biden’s term, 8.2% of the population, or 27.2 million people, were uninsured, according to the NHIS’ estimates, which measure those uninsured at the time they were interviewed. A Census Bureau report, released in September and measuring those who were uninsured for the entire calendar year, similarly put the uninsured rate at 8%.

Under Biden’s full term, the percentage and number of Americans who are uninsured declined, as we explained in our “Biden’s Final Numbers” report.

Judiciary Appointments

In his first term, Trump filled one-third of the Supreme Court, nearly 30% of the appeals court seats and nearly 26% of District Court seats. So far in his second term, the judiciary confirmation numbers lag a bit behind those in Biden’s first year.

Supreme Court — There hasn’t been a vacancy on the Supreme Court during the first year of Trump’s second term, just as there wasn’t a vacancy in Biden’s first year.

Court of Appeals — As of Jan. 16, Trump has won confirmation for six U.S. Court of Appeals judges. At the same point in his term, Biden had won confirmation for 12.

District Court — Twenty-one Trump nominees to be District Court judges have been confirmed, while 29 were confirmed at the same point in Biden’s first year.

Two U.S. Court of Federal Claims judges also were confirmed in Biden’s first year. None have been confirmed so far under Trump, and there are no vacancies for such positions.

As of Jan. 16, there were no vacancies for Court of Appeals judges, 39 for District Court judges with five nominees pending, and one vacancy for the international trade court.

Sources

We provide links to the sources for these statistics throughout the article.

Editor’s note: FactCheck.org does not accept advertising. We rely on grants and individual donations from people like you. Please consider a donation. Credit card donations may be made through our “Donate” page. If you prefer to give by check, send to: FactCheck.org, Annenberg Public Policy Center, P.O. Box 58100, Philadelphia, PA 19102.

www.factcheck.org (Article Sourced Website)

#Trumps #Numbers #Term #FactCheck.org