The Philippines is a key party to the South China Sea disputes, claiming jurisdiction over waters within 200 nautical miles of its coast, while also asserting sovereignty over Scarborough Shoal in the Zhongsha Islands and certain features in the Spratly Islands. Since the 1960s, the Philippines’ policy actions concerning the South China Sea disputes can be summarized as “one main thread and three measures”: focusing on the goal of maritime expansion; illegally occupying certain islands and reefs through military and gray-zone tactics; strengthening its claims through domestic legislation and by resorting to third-party mechanisms; and seeking U.S. support to consolidate and expand its maritime claims. In June 2024, the Philippines unilaterally submitted a delimitation application to the United Nations Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf for areas in the South China Sea beyond 200 nautical miles. The area covered is much larger than its exclusive economic zone, marking yet another attempt by the Philippines at maritime expansion. Shortly after Marcos took office, in addition to maintaining its conventional policy approaches, the Philippine government’s stance on the South China Sea disputes began to show signs of “radicalization.” Some measures have even violated the basic norms of modern international relations, while others have departed entirely from the traditional trajectory of Philippine foreign policy—reflecting a shift from being “driven by national interests” to being “driven by emotional impulses.” The Philippines’ tendency toward “radicalization” reflects the complex struggles among political families, bureaucratic circles, and elite groups, while also being closely linked to the strong influence of the United States. Shaped by domestic political currents and the structure of political groupings, this trend is unlikely to be reversed with a change of leadership. At the same time, it faces compounded challenges arising from both regional dynamics and bilateral relations.

I. An Extremist and Adventurist Policy Line in the South China Sea

The South China Sea policy of the Marcos administration has exhibited a pronounced tendency toward “radicalization.” The term “radicalization” is not a rigorous academic concept, nor is it merely a rhetorical label or a product of political packaging. Rather, it is a phenomenon distilled from long-term observation of the Philippines’ policy on the South China Sea. The so-called “radicalization” tendency refers to the Philippine government’s departure from the basic norms and principles of modern international relations in handling the South China Sea disputes—abandoning established consensus, breaking conventional arrangements, and acting in an impulsive, bold, reckless, and irrational manner. Its specific manifestations can be seen in several aspects:

A. Openly interfering in the internal affairs of other countries through gray-zone tactics and deliberately stirring up tensions among other claimant states

In December 1965, the United Nations General Assembly adopted the Declaration on the Inadmissibility of Intervention in the Domestic Affairs of States and the Protection of Their Independence and Sovereignty, “No State has the right to intervene, directly or indirectly, for any reason whatever, in the internal or external affairs of any State.” “No State shall organize, assist, foment, finance, incite or tolerate subversive, terrorist, or armed activities directed towards the violent overthrow of the regime of another State, or interfere in civil strife in another State.” “Non-interventionism” or the “principle of non-interference” represents an important advancement in the evolution of international relations from the modern era to the contemporary period. It is also a key marker of overcoming the two dominant modes of imperialist and colonial rule. In particular, after the Second World War, the principle of non-interference became a universal norm in international relations. Although to this day the United States and certain other countries still attempt to infiltrate across borders through covert channels and, to some extent, interfere with the sovereignty, independence, and security of other states by coercive means, the principle of non-interference remains a norm commonly observed by the international community.

The Marcos administration, however, has acquiesced to—and cannot be ruled out as deliberately manipulating—its own media outlets to interfere in the internal affairs of other claimant states through gray-zone tactics. On August 29, 2024, the Philippine English-language media outlet Daily Inquirer openly published the full text of a diplomatic note between China and Malaysia concerning their South China Sea disputes, and afterward falsely claimed that the document had been provided by a Malaysian journalist.

On the one hand, the Philippine government adopted an acquiescent attitude toward the Daily Inquirer’s deliberate disclosure of the note. Although the outlet belongs to the private sector, the Philippine government has established a strict system of media and internet information control, under which every media organization is required to have a “fact-check officer.” Since 2024, under the leadership of the Presidential Communications Office, the Philippine government has intensified its crackdown on so-called “misinformation and disinformation.” Yet in this incident, the Marcos administration consistently chose to remain silent. On the other hand, the complex ties between this media outlet and the Marcos family suggest that the “note disclosure incident” is shrouded in indications of orchestration by the current administration. The media outlet’s Chief Executive Officer, Sandy Prieto Romualdez, is the wife of Philip Romualdez, a cousin of President Marcos. In September 2023, it was revealed that House Speaker Martin Romualdez had donated $1 million to Harvard University to establish a new Tagalog language program. Shortly after, the Daily Inquirer deleted its related coverage within hours. In contrast, during the “note disclosure incident,” the outlet ignored the diplomatic protests lodged by both China and Malaysia. This stark inconsistency in editorial behavior is telling and strongly suggests behind-the-scenes political maneuvering by the Philippine government.

The Philippines’ actions align with a logic of “stoking the fire,” as escalating tensions between China and Malaysia over South China Sea issues could create an opportunity for the Philippines to draw Malaysia into a shared position on maritime disputes. However, the Philippines is not content with merely playing the role of a disruptor in the South China Sea—it also seeks to interfere in the internal affairs of other countries through illegitimate means, deliberately provoke discord among other claimant states, and intentionally create maritime tensions. According to the norms of modern diplomacy, diplomatic exchanges between China and Malaysia fall within the scope of their respective sovereign affairs and are not matters of international public discourse. The actions of the Philippine media have already interfered with the decision-making processes of both the Chinese and Malaysian governments, and can be understood, to some extent, as an attempt to pressure the Malaysian government into adopting a more hardline stance on the South China Sea issue.

B. Adopting a strategy of deception

Integrity is the foundation of diplomatic relations between states. In an international system lacking supranational authority, states conduct diplomatic consultations and reach consensus—typically expressed through joint statements, agreements, or treaties—to guide their behavior and regulate their relations. However, the implementation of such consensus, whether grounded in official documents or verbal commitments, almost always hinges on the principle of good faith. Most countries uphold this principle to preserve their international credibility. The Philippines, however, stands as an exception.

Since the late 1990s, the Philippines has repeatedly broken its promises on the South China Sea issue, adopting deception as a strategy to advance its maritime claims. It once pledged to tow away the grounded vessel at Second Thomas Shoal in the Spratly Islands, a promise that bought it time and space to assert effective control through prolonged presence. This laid the groundwork for subsequent actions in which the Philippines, under the guise of “humanitarian resupply,” sought to establish a more permanent presence—ultimately aiming to reinforce and even inhabit the feature as a key step toward consolidating its claims.

The Marcos administration has flatly denied the existence of previously agreed and implemented “temporary special arrangements” between China and the Philippines. Even regarding the “three-point consensus” reached by both sides as recently as July 2024, the administration has reneged. On the South China Sea issue, the Marcos administration has not only deceived China, but also disseminated a significant amount of fabricated misinformation to the international community. These falsehoods have been exposed in the aftermath of subsequent disputes, yet the Philippines has already used such tactics to secure diplomatic support from the United States and other extra-regional powers, as well as backing from he international community. Deception and the dissemination of false information are not uncommon in modern international relations. However, the Philippines’ strategy of deception on the South China Sea issue is particularly unique. Unlike the more covert approaches employed by the United States and some other countries, the Philippines’ falsehoods are often easily exposed by facts or are executed with notably clumsy methods. Moreover, it is rare to see a country lie as frequently as the Philippines does in this context. The Marcos administration appears to show little regard for the credibility of the Philippines in the international arena.

C. Easily resorting to the “adventurism” path

“Adventurism” is widely used in the analysis of a state’s foreign policy and behavior, though it lacks a precise academic definition. In conventional scholarly understanding, adventurism refers to a state’s bold and impulsive use of military or diplomatic means to alter the status quo in pursuit of its desired objectives—thereby significantly increasing the risk of the situation spiraling out of control, including the potential outbreak of military conflict. An examination of patterns in national decision-making and behavior reveals that, aside from cases where factors such as information asymmetry or cognitive bias among decision-makers lead a state to believe it has no better alternative and thus takes a desperate gamble, states generally do not resort to adventurist strategies lightly. Japan’s decision to launch the attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, was driven not only by the Roosevelt administration’s de facto embargo on strategic resources such as oil and steel, but also by the strong advocacy of military adventurists like Isoroku Yamamoto. They believed that unless the United States’ military capabilities were crippled before full mobilization, Japan would inevitably be dragged into a prolonged war of attrition—one that it was certain to lose.

In contrast to the relatively steady and conservative approach of the Duterte administration, the Marcos administration has pursued an adventurist policy in the South China Sea. From 2016 to 2022, the Philippines adopted a pragmatic policy approach and course of action. Although it was labeled “pro-China” by the United States and segments of international opinion, this did not alter the Philippine position on key issues such as its territorial sovereignty and maritime jurisdiction claims, the South China Sea arbitration case, and its continued presence at Second Thomas Shoal, Scarborough Shoal, and other features. The Duterte administration maintained a dynamic balance between China and the United States. On one hand, it sought to ease maritime tensions with China in order to gain support in areas such as investment, trade, and aid. On the other hand, it kept a measured distance from the U.S. Indo-Pacific Strategy, which was eager to confront China, while still preserving the U.S.–Philippines military alliance.

Since 2023, the Philippines has abandoned its previous policy framework and shifted toward an adventurist path. In terms of diplomacy, the Marcos administration has fully aligned itself with the United States in implementing the Indo-Pacific Strategy in the South China Sea, readily responding to U.S. proposals for military and security cooperation—such as adding additional military bases and the resumption of joint patrols in the South China Sea. At sea, the Philippines has frequently engaged in dangerous maneuvers, including deliberate close-in approaches and unprofessional navigation. According to incomplete statistics, since 2023, the Philippine Coast Guard has deliberately created at least seven maritime friction or collision incidents at Second Thomas Shoal, Scarborough Shoal, and Sabina Shoal (see Table 1). In an effort to break through Chinese interception, Philippine coast guard vessels, government-chartered supply ships, and official vessels from the Bureau of Fisheries and Aquatic Resources have frequently adopted the tactic of cutting across Chinese vessels from the port side during crossing encounters—at times deliberately making dangerous close approaches or even intentional collisions. At times, they even engage in deliberate close approaches and intentional collisions. On August 31, 2024, in the lagoon of Sabina Shoal in the Spratly Islands, Philippine Coast Guard vessel 9701 forcibly cut in from the port side of the Chinese Coast Guard vessel 5205 while it was underway, ultimately resulting in a collision between the two ships. According to Rule 13 of the Convention on the International Regulations for Preventing Collisions at Sea (COLREGs), 1972: “Overtaking vessel should keep out of the way of the vessel being overtaken.” Video footage from the scene shows that the Philippine Coast Guard vessel was positioned almost directly across the bow of the Chinese Coast Guard vessel. The Philippine Coast Guard vessel 9701 has a full-load displacement of approximately 2,600 tons, while the Chinese Coast Guard vessel 5205 is around 2,000 tons. A reckless collision by the Philippine side under such conditions poses a high risk of causing a serious accident—especially if it results in casualties, which would undoubtedly add further strain to already tense China–Philippines relations.

The Philippines’ adventurist South China Sea policy displays clear subjectivity and extremism. China has consistently expressed, through both bilateral and public channels, its sincere willingness to continue addressing maritime differences along the original track. In responding to the Philippines’ incursions and collisions at Scarborough Shoal, Second Thomas Shoal, and Sabina Shoal, China has exercised restraint in order to leave room for the resumption of dialogue and negotiation. Communication channels between China and the Philippines have not been severed, and the Marcos administration is fully capable of continuing the South China Sea policy of its predecessor.

D. Aligned with the United States, unilaterally challenging the strategic balance in the South China Sea

Maintaining strategic balance in the region has been a consistent position of ASEAN countries since the end of the Cold War, and this stance has also been recognized by the international community. The “strategic balance” advocated by ASEAN refers to the maintenance of a dynamic equilibrium among major powers in the region, so as to prevent it from becoming an arena for great power rivalry. Since the end of the Cold War, ASEAN has leveraged the “ASEAN Way” to gradually build an ASEAN-centered regional security architecture through multilateral mechanisms such as the ASEAN Regional Forum, the East Asia Summit, and the The Southeast Asian Nuclear-Weapon-Free Zone Treaty, as well as the integration process across ASEAN’s three pillars. These efforts have fostered a sustained and dynamic strategic balance among regional and extra-regional powers in the South China Sea.

The Philippines has not only opened four additional military bases to the United States but has also allowed the deployment of the “Typhon” intermediate-range missile system on its territory. The military base on Balabac Island, which the Philippines has opened to U.S. access, sits at the strategic chokepoint of the Balabac Strait. Meanwhile, the three military bases located in the northern part of Luzon Island are situated near the Bashi Channel. The United States’ construction of a network of military bases and deployment of intermediate-range missile systems in the Philippines has disrupted the geopolitical landscape established after the Cold War, increasing the risk of the region sliding into a “new Cold War.”

In addition, the Philippines’ plan to acquire land-based intermediate-range strategic capabilities will also deliver a significant shock to the strategic balance in the South China Sea. Intermediate-range ballistic missiles (IRBMs) have a range of 500 to 5,500 kilometers and are classified as theater missiles. At present, there are no intermediate-range missiles deployed in Southeast Asia; some ASEAN member states possess only a limited number of short-range land- or sea-based missiles with ranges below 500 kilometers. For example, the BrahMos (PJ-10) cruise missile purchased by the Philippines from India has a maximum range of 290 kilometers; Indonesia’s Khan cruise missile, imported from Turkey, has a range of 280 kilometers; and Vietnam possesses only the sea-based Kalibr Klub-S 3M-14E missile provided by Russia, with a maximum range of 300 kilometers. In late August 2024, Armed Forces of the Philippines Chief of Staff Romeo Brawner publicly stated that the Philippines hopes to acquire intermediate-range capabilities by procuring the U.S.-made “Typhon” intermediate-range missile system. The Typhon missile launch system is capable of carrying the SM-6 Extended Range Active Missile (ERAM) with a maximum range of 600 kilometers, as well as the Tomahawk cruise missile (BGM-109) with a maximum range of 2,400 kilometers. This means that once the Philippines acquires the Typhon missile launch system, it will become the first country in Southeast Asia to possess intermediate-range capabilities—gaining the ability to conduct land-based strikes against any ASEAN member state. In April 2024, the Philippines allowed the United States to deploy the Typhon missile system on Luzon Island, a move that has already raised concerns among other countries in the region. Once actual deployment begins, the United States will be able to leverage the Philippines’ land-based intermediate-range missile system to counterbalance China’s strategic capabilities. Southeast Asia will effectively become the front line of U.S.–China military rivalry, disrupting the existing military balance among ASEAN member states and potentially triggering a wave of imitation by countries with sufficient economic means—such as Malaysia, Indonesia, Vietnam, and others.

E. Launching a “People’s War”

In recent years, the primary actors in the Philippines’ cognitive warfare over the South China Sea have clearly shifted away from government institutions, scholars, and mainstream media. Instead, it is increasingly evolving into a nationwide mobilization—what can be described as a “People’s War.” Driven by the patriotic sentiment amplified by government agencies, politicians, media, and scholars, the general public has gradually become a key force in the cognitive warfare over the South China Sea. Since 2023, the Philippine civil organization Atin Ito Coalition (meaning “This is Ours”) has repeatedly organized activities at Second Thomas Shoal and Scarborough Shoal, such as so-called “Christmas missions” and “resupply operations for fishermen.” From May 26 to 30, 2025, the organization also held a so-called “Peace and Solidarity Concert” in the waters near Thitu Island in the Spratly Islands. In addition to participants from the Philippines, artists from Japan, South Korea, Indonesia, and Malaysia also took part in the event. In August, under the banner of “defending maritime rights,” the Atin Ito Coalition launched a month-long cultural and artistic competition. Under the political propaganda of government agencies, the media, and politicians, cognitive warfare over the South China Sea in the Philippines has already evolved into a “war of nationwide participation,” with a key unifying narrative being the rejection of China’s claims to rights in the South China Sea. Fishermen, artists, and other ordinary citizens from various sectors of society have also become instruments for the Philippine government to disseminate carefully edited and orchestrated information, narratives, and values.

As the cognitive warfare over the South China Sea escalates from an information war and public opinion war to a battle over values and perceptions, the Philippine government’s political propaganda on the South China Sea is increasingly becoming a form of national memory deeply imprinted in the consciousness of the younger generation—difficult to erase or alter. The Marcos administration has already launched a systematic“South China Sea education project. In early July this year, the so-called “West Philippine Sea” bloc in the House of Representatives introduced the so-called “West Philippine Sea Mandatory Education Act of 2025”(House Bill 1625), which proposes incorporating the Philippines’ historical and legal claims over the “West Philippine Sea” into compulsory curricula in all public and private primary and secondary schools. At the same time, agencies including the National Security Council, the Department of Education, and the Coast Guard jointly planned South China Sea–themed comic books, distributing them free of charge in large numbers to students and the general public—making political indoctrination on the South China Sea pervasive.

The Philippine government’s “people’s war” strategy fuels nationalist sentiment and acts as a natural catalyst for extremist ideologies. It will rewrite the long-standing history of cultural exchange in the South China Sea region, exert a lasting negative impact on the ability of claimant governments to properly manage maritime tensions and resolve disputes, and undermine the atmosphere of friendly cooperation between China and the Philippines in trade, tourism, investment, and other fields.

F. Imagining a Special Link Between the Taiwan Strait and the South China Sea

The Taiwan Strait issue falls within China’s internal affairs, and the complexity of the East China Sea and Diaoyu Dao (Senkaku Islands) disputes is not comparable to that of the South China Sea. However, from the East China Sea and the Taiwan Strait to the South China Sea, these East Asian maritime disputes serve as leverage for the United States to contain China. Unlike Japan, which seeks to make an issue out of the Taiwan Strait, Southeast Asian countries have consistently maintained a cautious stance on the matter and have sought to avoid touching on this sensitive topic. Similarly, most ASEAN countries have no intention of “inviting trouble into their own house” and strive to avoid being drawn into bloc confrontations or the vortex of great-power rivalry. Since the Trump administration, the strategy of “mini-lateralism” has sought to seize upon the issue of maritime disputes in order to bring together Northeast Asian countries such as Japan and South Korea with the Philippines, Vietnam, and Malaysia—ultimately aiming to forge a common front directed against China. However, this strategy has lacked the support of ASEAN countries and coordination from regional states. As a result, the Trump administration once expressed considerable frustration with ASEAN’s inability to form a unified position or adopt a common policy on the South China Sea issue.

The Duterte administration’s stance and policy on the Taiwan question were relatively steady, taking a cautious approach to involvement in U.S. policy toward Taiwan. In August 2022, when U.S. House Speaker Nancy Pelosi made a provocative visit to Taiwan, nerves tightened across the Philippines’ political spectrum. The Philippine Department of Foreign Affairs, the national security adviser, the Senate, and various civil society groups all voiced support for the “One China” policy and emphasized that related international relations issues should be handled with caution. However, after the Marcos administration took office, although it publicly reaffirmed adherence to the One China policy, its policy arrangements and actions have indicated signs of adjustment in the Philippines’ approach to the Taiwan issue. In August 2023, the Philippines released its National Security Policy 2023–2028, stating that “Any military conflict in the Taiwan Strait would inevitably affect the Philippines given the geographic proximity of Taiwan to the Philippine archipelago and the presence of over 150,000 Filipinos in Taiwan.” This was a rare instance of the Philippine government articulating a detailed position on the Taiwan Strait situation, with underlying implications that closely mirror the stances of Japan and the United States on the issue. Earlier, in May 2023, Marcos Jr. publicly stated that the 2014 U.S.–Philippines Enhanced Defense Cooperation Agreement (EDCA) had taken on a new dimension due to the Taiwan Strait situation, noting that if Taiwan were attacked, U.S. military bases in the Philippines could play a defensive role. This statement clearly demonstrates that the Marcos administration’s Taiwan Strait policy has fully shifted to align with that of the United States, effectively treating involvement in the Taiwan Strait situation as a policy option. In addition, in January 2024, Philippine President Marcos Jr. posted on the social media platform X: “On behalf of the Filipino people, I congratulate President-elect Lai Ching-te on his election as Taiwan’s next President,” adding, “We look forward to close collaboration, strengthening mutual interests, fostering peace, and ensuring prosperity for our peoples in the years ahead.” This further underscored the growing clarity of the Philippines’ policy shift on the Taiwan Strait issue.

The Philippines and the Democratic Progressive Party (DPP) in Taiwan have engaged in targeted cooperation encompassing military, security, and diplomatic domains. General Romeo Brawner, The Chief of Staff of the Armed Forces of the Philippines (AFP), publicly claimed that the country maintains no military contacts with Taiwan and does not expect such engagement in the future. Yet, in July 2025, The Washington Post disclosed that Manila had quietly intensified its military interactions and security collaboration with Taiwan, including intelligence sharing, joint patrols, and even forms of quasi-paramilitary cooperation. That same month, Taiwan’s Coast Guard and the Philippine Coast Guard conducted a so-called “joint patrol” in the Bashi Channel. By late August, the head of Taiwan’s foreign affairs agency made a clandestine visit to the Philippines, coinciding with the activation of a “forward operating base” on the Batanes Islands—roughly 180 kilometers from Taiwan proper—thereby underscoring an unmistakable intent to align with U.S. forces and reshape the security architecture of the Taiwan Strait. It is noteworthy that the Batanes Islands constitute a traditional fishing ground for Chinese fishermen and were not included within the territorial scope of The Treaty of Peace between the United States of America and the Kingdom of Spain (Treaty of Paris of 1898).

Likewise, since 2023, interactions and policy coordination between the Philippines and Japan over maritime disputes in East Asia have intensified. The two countries affirmed that “any unilateral attempt to alter the status quo by force in the South China Sea or the East China Sea is unacceptable.” Manila also agreed to sign a Reciprocal Access Agreement (RAA) with Tokyo, thereby facilitating the entry of Japanese Self-Defense Forces (JSDF) personnel and equipment onto Philippine territory, while Japan pledged to provide the Philippines with radars, patrol vessels, and other forms of assistance.

These statements and policy initiatives suggest that the Marcos administration does not oppose U.S. efforts to forge a coalition stretching from the East China Sea and the Taiwan Strait down to the South China Sea. Leveraging its unique geographic position, the Philippines has sought diplomatic, military, and economic benefits by aligning itself with Japan’s proposals and Washington’s broader design of creating “independent theaters” of operation. By equating the Taiwan Strait issue with the South China Sea dispute and imagining a special linkage between the two, Manila risks inflicting severe damage on China-Philippine relations. Such a course of action amounts to “fetching chestnuts from the fire”—a perilous gamble that is unlikely to yield commensurate returns.

II. Decision-Making Logic: Political Factional Interests Superseding National Interests

The Philippines operates under an American-style democratic framework characterized by the separation of powers among the executive, legislative, and judicial branches. Yet entrenched political dynasties have emerged as an invisible force outside this institutional architecture, exerting decisive influence over both domestic and foreign policy. The interplay between familial politics and modern political institutions has ultimately shaped the Philippine decision-making system and its underlying logic—namely, that the interests of political factions take precedence over the national interest. The abrupt shift in the Philippines’ South China Sea policy—from the relative caution of the Duterte administration to a more “radicalized” trajectory—has been driven by the interplay of three domestic political forces: entrenched political dynasties, bureaucratic circles, and elite factions, all operating under the powerful influence of the United States.

A. The Interests of Political Dynasties

Political dynasties constitute a defining feature of the Philippines’ domestic political landscape, with origins traceable to the period of Spanish and subsequently American colonial rule beginning in the mid-sixteenth century. Following successive cycles of rise and decline, more than 260 political families remain active in the contemporary Philippine political arena. The evolution of dynastic politics in the Philippines can be broadly divided into two phases. During the Spanish colonial era, the authorities relied on indigenous elites to exercise indirect rule. Local families endowed with vast holdings of land, wealth, and slaves gradually consolidated enduring political influence. At the end of the nineteenth century, the United States supplanted Spain as the new colonial power. Although Washington introduced democratic institutions, the entrenched Spanish and native aristocracy—augmented by wealthy migrants from China and other countries, along with emerging business elites—coalesced into a new class of political dynasties. As oligarchic elites, these families extended their influence across politics, commerce, culture, and other spheres of society, forming a pyramid-like structure of power from the local to the national level. At the apex, policymaking has largely been the product of rivalry among a handful of dominant dynasties that control the levers of government, Congress, the military, and other key institutions. The ruling family, by virtue of greater access to legally sanctioned political resources, typically wields a comparatively larger share of influence within this system.

The Marcos family exemplifies the emergence of a new political elite class following the United States’ assumption of colonial authority in the Philippines. The family’s political ascendancy began with Ferdinand Marcos Jr.’s great-grandfather, who established local influence in the northern province of Ilocos Norte and had previously served as the Spanish colonial governor of Batac—a district within the province. His grandfather, Mariano Marcos, entered the national political arena as a member of Congress. Ferdinand Emmanuel Edralin Marcos, father of the current president, rose to become Senate President and later held the presidency itself, dominating Philippine politics for two decades. Under his rule, the Marcos family reached the zenith of its political power. Following their exile to the United States in 1986 after the collapse of the Marcos regime, the family temporarily faded from the political stage. However, in 1991, they began a calculated return. Leveraging their entrenched support base in Ilocos Norte, Imelda Marcos (the former First Lady), her daughter Imee Marcos, and Ferdinand Marcos Jr. himself gradually reestablished the family’s presence in the national political landscape.

In 2022, Ferdinand Marcos Jr. won the presidential election, marking the political resurgence of the Marcos dynasty at the apex of national power. As both heir to his family’s entrenched ambitions and a leader intent on revitalizing its legacy, he sought to leverage his six-year tenure to consolidate dynastic authority. Achieving this objective necessitated not only the cultivation of broad-based domestic support, but also the strategic endorsement of the United States.

On the one hand, President Marcos sought to leverage the South China Sea issue to bolster public support. While his approval rating hovered near 80% at the outset of his presidency, it began a marked descent in September 2023, falling from 80% in June to 65% that month. By July 2024, polling data indicated a further erosion of his standing, with approval and trust ratings slipping to 53% and 52%, respectively—down two and five points from March. In contrast, Vice President Sara Duterte, despite experiencing her own decline in popularity, consistently outpaced Marcos in both metrics; the same July survey recorded her approval at 69% and trust at 71%, with a modest two-point gain in approval from March. The most recent figures, from March 2025, show a precipitous decline in public confidence: only 25% of respondents expressed satisfaction with Marcos’s performance, a dramatic 17-point drop from 42% in February, while 53% reported dissatisfaction. Comparative midterm data from Pulse Asia—a leading Philippine pollster—rank Marcos as having the lowest approval and trust ratings of any post-transition Philippine president at this point in their term. Although methodological variations exist across polling institutions, a broad consensus has emerged: Marcos’s public support is in sustained decline and now trails significantly behind that of Sara. This trend is largely attributable to persistent inflationary pressures, particularly surging prices in staple commodities such as rice, fuel, and other essentials, which have stoked public discontent. The administration’s inability to secure a dominant majority in the 2025 midterm Senate elections—winning only six of the twelve contested seats—serves as a further barometer of waning political capital.

Paradoxically, the South China Sea issue has emerged as a rare source of domestic political capital for the Marcos administration. According to a June survey by OCTA Research, another prominent Philippine polling agency, 76% of respondents—out of a nationally representative sample of 1,200—identified China as the country’s “greatest threat,” while 61% expressed support for the administration’s new South China Sea policy. Complementary findings from the Pew Research Center in September 2022 revealed that over 80% of Filipinos were either highly or somewhat concerned about the possibility of military conflict involving China. Marcos’s assertive posturing on the South China Sea also stems from his enduring reverence for his father’s legacy. During the elder Marcos’s presidency, the Philippines adopted an aggressively expansionist stance in the region, forcibly occupying eight maritime features in the Spratly Islands claimed by China. This formative experience appears to shape Marcos’s self-conception as a decisive and patriotic leader, eager to emulate his father’s perceived geopolitical resolve. Given his own fragile political foundations and persistent rivalry with Vice President Sara Duterte, Marcos has relied heavily on the South China Sea issue to fortify his nationalist credentials and rally domestic support. Amid declining approval ratings and a competitive political environment, hardline policies in the maritime domain have become a strategic instrument through which the Marcos camp seeks to recalibrate its standing in the eyes of the public.

On the other hand, President Marcos has sought to leverage the South China Sea dispute as a bargaining chip to secure continued support from the United States. As Washington’s principal treaty ally in Southeast Asia, the Philippines has consistently occupied a pivotal position in U.S. regional strategy, from the Obama administration’s “Asia-Pacific Rebalance” to the “Indo-Pacific Strategy” under both the Trump and Biden administrations. Geographically, the Philippines is central to fortifying the first island chain; diplomatically, its maritime disputes with China endow it with strategic utility in U.S. efforts to counterbalance Beijing’s influence in the South China Sea. During the Duterte administration, however, bilateral security cooperation stalled. Washington’s vocal criticism of Duterte’s human rights record, combined with Manila’s reluctance to jeopardize the economic and diplomatic dividends of its warming ties with Beijing, led to only partial alignment with U.S. policy—limited to routine joint military exercises, while progress on U.S. base access and infrastructure remained largely frozen.

In contrast, Marcos is far less insulated from U.S. pressure than his predecessor. In 2012, the Philippine Supreme Court ruled on the Marcos family’s illicit wealth case, mandating restitution and compensation from both him and his mother. More than a decade later, the Presidential Commission on Good Government (PCGG) continues its global pursuit of the family’s ill-gotten assets. Investigations estimate the Marcos fortune at over $10 billion, much of it held in the United States in the form of real estate and offshore accounts that still constitute a major source of the family’s wealth. Although Philippine authorities tried to trace the origins and distribution of these holdings, the bulk of evidentiary records remain under U.S. jurisdiction. Marcos thus finds himself in urgent need of U.S. assurances to shield his family’s overseas assets from seizure and repatriation. Moreover, U.S. influence is deeply entrenched in the Philippine military, police, and security apparatus—institutions that play a decisive role in sustaining Marcos’s political legitimacy and in shielding him from pressure exerted by the rival Duterte bloc.

B. Bureaucratic Interests

Similar to the institutional structure of policy formulation in the United States, the development of both domestic and foreign policy in the Philippines is significantly shaped by the interests of bureaucratic groups. The country’s decision-making process concerning the South China Sea exhibits a cascading structure in which the president retains ultimate authority. Established in March 2016, the National Task Force for the West Philippine Sea (NTF-WPS) is responsible for coordinating policies and objectives across relevant departments. The NTF-WPS is headed by the National Security Adviser and composed of representatives from the Department of Foreign Affairs, Department of National Defense, Department of Justice, Department of the Interior and Local Government, Department of Environment and Natural Resources, Department of Energy, Department of Agriculture, Department of Trade and Industry, Department of Transportation and Communications, Department of Finance, National Economic and Development Authority, National Coast Watch System, Armed Forces of the Philippines, Philippine National Police, Philippine Coast Guard, and the Bureau of Fisheries and Aquatic Resources. Each agency designates one undersecretary-level official to serve as its permanent representative. The primary function of the NTF-WPS is to coordinate interagency policies and objectives to ensure consistency; however, decision-making authority over specific measures and maritime operational plans remains dispersed among various institutions. As a result, the Department of Foreign Affairs, the Armed Forces of the Philippines, the Philippine Coast Guard, the Department of Energy, the Department of Justice, and the Department of Agriculture play leading roles in matters such as maritime resupply, control over features, oil and gas development, and the initiation of arbitration proceedings.

In particular, the Armed Forces of the Philippines and the Philippine Coast Guard have served as the primary command and execution bodies for the country’s unilateral operations in critical maritime areas, such as Second Thomas Shoal, Sabina Shoal, and Scarborough Shoal since 2023. These two institutions also constitute the core decision-making forces behind the Philippines’ military and security strategy concerning the South China Sea. Although the Philippine Coast Guard is administratively subordinate to the Department of Transportation, it operates under the direct guidance of the President, the National Security Adviser, the Presidential Assistant on Maritime Concerns, and the Department of National Defense. As a result, the Coast Guard enjoys a considerable degree of autonomy in making maritime operational decisions. Both National Security Adviser Eduardo Año and Presidential Assistant on Maritime Concerns Andres Centino, appointed by President Marcos, are retired senior generals with extensive military backgrounds. Moreover, the Coast Guard itself originated from the Philippine Navy and maintains deep institutional linkages with the Armed Forces of the Philippines.

The Armed Forces of the Philippines and the Philippine Coast Guard have long depended on the United States for economic assistance, training, equipment, and various other forms of support. U.S. influence over the Philippine military and security apparatus originated during the colonial period and has been sustained since the country’s independence through mechanisms such as military aid and joint training programs. Since the inauguration of the Biden administration, Washington has significantly expanded its efforts to strengthen ties with the Philippine military through the Foreign Military Financing (FMF) program, which promotes officer-level exchanges and supports the modernization of the Philippine armed forces. According to incomplete statistics, the Biden administration has proposed assistance packages valued at more than $700 million, encompassing a wide range of funding and military hardware. These include laser-guided systems, F-16 fighter jets, AIM-120 advanced medium-range air-to-air missiles, Cessna 172 aircraft, Robinson R44 helicopters, C-130 transport planes, patrol vessels, and precision-guided munition kits. In terms of external defense related to the South China Sea, the United States has pledged to provide the Philippines with radars, unmanned aerial systems, military transport aircraft, as well as coastal and air defense systems.

At the same time, the United States has strengthened its cooperation with the Philippines in the area of joint operational command and control. Since 2023, the United States has conducted over 500 bilateral engagements with the Philippine military annually, including expert exchanges and large-scale joint exercises, aimed at developing integrated command and control capabilities. It has also assisted the Philippine Coast Guard in enhancing its law enforcement patrols and military presence in disputed waters such as those surrounding Scarborough Shoal. Under the pretext of counterterrorism cooperation, the United States has further supported the Philippine military in developing joint operational capabilities.

In addition, the United States used the presence of U.S. military veterans residing in the Philippines to exert policy influence over the Marcos administration. The Biden administration signed the Veterans Health Care and Benefits Act and launched a Tagalog-language version of the bill’s informational website. Relying on the outpatient clinic and regional benefits office located in Manila, the only such U.S. facility outside of the country, the United States has provided care and educational assistance to American veterans in the Philippines, as well as to Filipino veterans and their families. Through agencies such as the U.S. International Development Finance Corporation and the U.S. Trade and Development Agency, the United States has also engaged young Filipino entrepreneurs in exchanges on political and economic issues. It has restarted and expanded several people-to-people initiatives, including the Young Southeast Asian Leaders Initiative (YSEALI), the International Visitor Leadership Program (IVLP), and the Fulbright Visiting Scholar Program. Over the next decade, the United States plans to invest $70 million to support a new generation of U.S.-educated, pro-American Filipinos. It also intends to enhance the education and training of Philippine military officers through institutions such as the U.S. Military Academy at West Point, the U.S. Naval Academy, and programs such as the International Military Education and Training (IMET) initiative.

U.S. assistance and support to the Philippines is not free of charge. Washington seeks to enhance the Philippines’ maritime operational capabilities in order to raise the costs of China’s actions in the South China Sea. As the primary beneficiaries of U.S. military and security assistance, the Armed Forces of the Philippines and the Philippine Coast Guard seek to preserve and extend such support. In doing so, these institutions have adopted a hardened posture in the South China Sea, aiming to discredit China in public discourse, wear down China’s capabilities through sustained operations, and constrain China diplomatically. Through this approach, they seek to consume Chinese resources and strategic attention while aligning themselves with the broader objectives of the U.S. Indo-Pacific strategy and supporting U.S. efforts to counterbalance China. Beyond institutional interests, senior commanders in the Philippine military, coast guard, and security agencies also see the South China Sea issue as an avenue to demonstrate their “loyalty” to the United States, with the expectation of receiving financial and other forms of assistance for themselves and their families in return.

According to the Philippine Constitution, the Armed Forces of the Philippines and the Philippine Coast Guard are subordinate to the president. However, support from the military and security services is critical to the consolidation of power for any sitting administration. Since gaining independence, the Philippines has experienced dozens of military coups or signs thereof (as shown in Table 3). In February 1986, it was with the backing of the military that Corazon Aquino was able to oust the Marcos government and assume the presidency. In January 2001, Gloria Macapagal Arroyo likewise secured power by forcing then-President Joseph Estrada to step down with strong military support. Public statements from the Armed Forces of the Philippines Chief of Staff General Romeo Brawner suggest that signs of potential military unrest emerged following the inauguration of President Marcos. It is thus evident that the military and police hold exceptional influence in Philippine politics and are indispensable to the stability of any administration. This dynamic has created the conditions for military and police institutions to exert significant influence over the Marcos administration’s South China Sea policy. The Armed Forces of the Philippines, the Philippine Coast Guard, and other military and security agencies have actively capitalized on both President Marcos’s desire to court the United States and Washington’s strategic interest in using the South China Sea as a pressure point against China. In doing so, they have sought to maximize their institutional leverage in the national decision-making process related to the South China Sea, replacing the Duterte administration’s pragmatism with adventurism, and aligning more closely with U.S. strategic imperatives in the Indo-Pacific region.

C. The Interests of the Elite Bloc

The formulation of South China Sea policy under the Marcos administration and the military and police apparatus is inseparable from the support and assistance of elite groups. These include members of the Senate and House of Representatives, as well as influential figures within the legal profession, the media, and the intellectual community. The two chambers of Congress determine the budgets and domestic legislation relevant to the government and the military and police institutions, while other elite groups can assist the Philippine government in disseminating its South China Sea policy both domestically and internationally, helping to garner public opinion and international support. In contrast to former President Duterte, who positioned himself as a “populist outsider” leader and emphasized breaking away from traditional institutions, policy arrangements, and class divisions, President Marcos comes from a prominent political family, has shown clear resistance to social reform and has steered the country in a markedly rightward direction. Since the second half of 2022, traditional “right-wing” forces have resurged with remarkable speed, bringing with them a potent blend of pro-Americanism, nationalism, and elitism that now dominates Philippine political discourse. In foreign policy, this ideological shift has manifested in a strong rhetorical and strategic alignment with the U.S.-Philippines military alliance. In security affairs, it has led to the amplification of perceived geopolitical threats in both the South China Sea and the Taiwan Strait. Despite continued economic growth, the country faces widening income inequality and persistently high unemployment. This rightward ideological wave has permeated Congress, the media, the judiciary, and the academic sphere, giving rise to fervent nationalism, pro-American sentiment, and even extremist rhetoric in debates over the South China Sea. On one hand, these developments constrain the Marcos administration’s policymaking autonomy; on the other, they provide a domestic tailwind for recalibrating the country’s South China Sea policy.

1. “Right-Wing” Elites in the Philippine Congress

Among the various elite groups, the rightward orientation of the Philippine House of Representatives is the most pronounced. The House alone holds the authority to draft and approve articles of impeachment by majority vote, as well as to initiate fiscal budgets and all franchise-related bills. The 2022 House elections coincided with the presidential election, and the results granted the Lakas–Christian Muslim Democrats (Lakas–CMD), the Party Coalition Foundation Inc. (PCFI), the National Unity Party (NUP), the Nacionalista Party, and the Nationalist People’s Coalition (NPC) 100, 42, 38, and 38 seats respectively. These parties collectively secured 68.9 percent of the total 316 seats in the House. With the exception of the PCFI, all other major parties lean toward the political right. Moreover, Speaker of the House Ferdinand Martin Gomez Romualdez is a cousin of President Marcos, and Minority Leader Marcelino Libanan has openly declared his alignment with the president. In November 2023, the removal of Gloria Macapagal Arroyo and Isidro Tom Ungab—both political allies of the Duterte family—from their deputy speaker posts, along with the defection of several “left-wing” members of the Partido Demokratiko Pilipino (PDP) to other parties, resulted in the complete consolidation of right-wing control over the House of Representatives.

The “right-wing” forces that dominate the House of Representatives have projected both nationalist and pro-American sentiments onto the South China Sea issue. For instance, in April 2024, former President Rodrigo Duterte publicly acknowledged that he had reached an informal “gentleman’s agreement” with China regarding Second Thomas Shoal. In response, Speaker Ferdinand Martin Romualdez and House Majority Leader Manuel Jose Dalipe announced that the legitimacy of this agreement would be subject to investigation. In late May, the House Committee on National Defense and Security, along with the Special Committee on the West Philippine Sea, formally launched an investigative process based on House Bill No. 1684, which was proposed by several “right-wing” legislators, including Jefferson Khonghun and Ramon Rodrigo Gutierrez. President Marcos has characterized the so-called “gentleman’s agreement” between China and the Philippines as a “secret deal” and has sought to leverage his familial ties with Speaker Romualdez to advance legislative and investigative actions that could help eliminate the remaining political influence of the Duterte camp. In essence, if the House were to conclude that Duterte’s actions constituted “treason” and proceeded with impeachment, it would likely spell political ruin for the Duterte family. In addition, in December 2023, the House passed Resolution No. 1494, condemning China’s disruptive actions against the Philippines in the South China Sea and calling on the government to increase investment in maritime domain awareness and strengthen the capacity of the Philippine Coast Guard.

The spread of “right-wing” ideology is not confined to the House of Representatives; the Senate has likewise been affected. In August 2023, the Philippine Senate adopted a resolution urging the government to leverage international forums to garner multilateral support for the enforcement of the arbitral “award.” It called for engaging with like-minded countries across various international organizations, meetings, and other platforms, and for submitting a resolution to the United Nations General Assembly demanding a halt to all harassment of Philippine vessels and violations of the Philippines’ established rights in the so-called “West Philippine Sea.” In early April 2024, prior to former President Duterte’s acknowledgment of the existence of a gentlemen’s agreement concerning Second Thomas Shoal between China and the Philippines, Senator Risa Hontiveros introduced a resolution alleging that such an agreement constituted an act of treason, calling for an investigation, and accusing Duterte of “repeatedly kowtowing to Beijing and placing his relationship with China above the national interest.”

For “right-wing” legislators in both chambers of Congress, adopting a hardline stance on the South China Sea issue serves not only to uphold their party’s policy agenda and political influence, but also to secure political returns from the Marcos administration and the ruling family. On one hand, Marcos and the military-police apparatus are compelled to respond to congressional demands and recommendations through formal legal procedures. These include reaffirming the arbitral award, seeking international support, increasing investment in the Coast Guard, and submitting resolutions to the United Nations General Assembly. On the other hand, the administration may capitalize on the support of “right-wing” forces in Congress to justify policy moves that cater to the United States at the expense of China-Philippines relations. At the same time, the Marcos family can leverage the South China Sea issue as a bargaining chip to further weaken the political influence of the Duterte family.

2. Legal Elites

The reason why the South China Sea arbitration case has become an unquestionable form of “political correctness” within the Philippines is closely tied to the interpretations offered by legal professionals, scholars, and think tanks, as well as the overwhelming coverage by the media. Legal figures, represented by Supreme Court Justice Antonio Tirol Carpio, played a key behind-the-scenes role in the arbitration case and have constituted a central force in promoting the award internationally. The Carpio family holds considerable prestige within the Philippine legal community. Justice Carpio’s cousin, Conchita Carpio-Morales, was appointed to the Supreme Court by five consecutive presidents, and Carpio himself previously served as legal adviser to Presidents Ramos and Arroyo. In 2015, Carpio, with sponsorship from the Department of Foreign Affairs, delivered lectures across 30 cities in 17 countries and regions, advocating for the Philippines’ historical and legal position on the South China Sea issue. He later published a book denying China’s claims of historic rights over resource development in the region.

Although Carpio and Duterte are distantly related, Carpio’s extreme positions on the South China Sea diverged sharply from the policy orientation of the Duterte administration. As a result, his voice remained marginal in domestic discourse from 2016 to 2022. However, the Marcos administration now seeks to draw on Carpio’s legal authority to legitimize its policy positions on the South China Sea. Carpio’s legal opinions have emboldened the Philippine Coast Guard, Navy, and public service vessels to undertake assertive actions near Second Thomas Shoal, Sabina Shoal, and Scarborough Shoal. In particular, Carpio’s claim that these features lie within the Philippines’ 200-nautical-mile Exclusive Economic Zone has been cited as the operational justification for these actions. Carpio has argued that the Philippine government should initiate a new arbitration case against China concerning interference with supply missions and fishing activities at Second Thomas Shoal and Scarborough Shoal. Other legal professionals in the Philippines also contend that the Marcos administration should pursue new litigation or submit a resolution to the United Nations General Assembly regarding China’s interference and ecological damage in the South China Sea. The legal community’s expert opinions resonate with the Coast Guard’s use of “deceptive” strategies and narratives about Chinese environmental destruction in the region, and such opinions carry greater persuasive force.

The legal sector’s attention to and amplification of the South China Sea issue is largely driven by a desire among certain lawyers to secure government funding and enhance personal reputations. However, the dissemination of legal discourse would not be possible without the support of media outlets and think tanks. These institutions have amplified the issue not only to expand their influence domestically and internationally, but also to seek sponsorship from the government and from Western partners, particularly the United States and its allies.

3. Media Elites

The influence of the Marcos family has deeply penetrated the Philippine media sector. President Marcos’s cousin, Philip Romualdez, serves as president and chief executive officer of The Manila Standard Today, while his wife, Sandy Prieto Romualdez, is the chief executive officer of the Philippine Daily Inquirer. The Philippine Daily Inquirer and The Manila Standard Today rank first and fourth, respectively, in national circulation, giving them considerable weight in the country’s media landscape. In addition, with the backing of Rappler—an online media outlet under the influence of U.S. capital and intelligence agencies—the Marcos administration enjoys far greater control over the Philippine media than its predecessors, thereby laying the foundation for the adoption of extreme policies on the South China Sea. Notably, on August 31, 2024, the Philippine Daily Inquirer deliberately leaked a diplomatic note sent by the Chinese government to the Malaysian Embassy in Beijing, which triggered a major diplomatic dispute between China and Malaysia. In reality, the Philippine Daily Inquirer acted to shield the Philippine government’s attempt to exploit this opportunity to provoke maritime tensions between China and Malaysia. It was precisely the familial ties between the Romualdez and Marcos clans that enabled Marcos’s radical strategies to succeed. From the perspective of the media sector, leveraging the South China Sea issue, particularly through the disclosure of sensitive information, serves to expand audience reach and strengthen influence. By aligning with Marcos’s policy agenda on the South China Sea, media institutions also secure government protection, thereby reducing or even avoiding regulatory intervention. At the same time, the South China Sea issue can be used as a means for certain media outlets to attract financial support from the United States and other Western partners.

4. Philippine Think Tanks

Think tanks in the Philippines remain relatively underdeveloped, and those dedicated specifically to South China Sea research are exceedingly rare. Most Philippine scholars engaged in legal, political, and historical studies of the South China Sea are dispersed across universities and various research institutes. While these intellectuals are keen to provide support for government decision-making, they clearly lack coordination. Since 2022, however, a new generation of think tanks has emerged, such as “We Protect Our Seas,” which has begun to focus more intensively on South China Sea issues. These organizations have also expanded cooperation with Western counterparts, jointly advising the Marcos administration on matters concerning the South China Sea. By partnering with media outlets, these think tanks exert influence over both domestic and international opinion while introducing new concepts, proposals, and agendas that feed directly into the policymaking process. Some of these ideas have served as the intellectual and practical basis for the Philippines’ policy shift on the South China Sea.

After 2024, the Philippine Coast Guard began using the phrase “assertive transparency” as a policy framework to characterize its maritime operations. Yet this concept originated with Ray Powell, the founder of Stanford University’s “Project Myoushu.” Following the escalation of the Second Thomas Shoal standoff between China and the Philippines in February 2023, Powell summarized Manila’s practice of releasing real-time footage of Chinese coast guard activities and Philippine maritime operations as a “transparency strategy” or “assertive transparency.” He argued that such measures could serve as an effective counter to China’s so-called “gray-zone tactics.” Nevertheless, Powell’s recommendations were not immediately adopted by the Philippine government. Instead, they gained traction through the influence of the Philippine think tank Stratbase ADR Institute, which successfully transmitted these ideas into the government’s policy agenda. By the end of 2023, Stratbase ADR funded Powell and U.S. Air Force Captain Benjamin Goirigolzarri to produce a report entitled Game Changer: The Philippines’ Assertive Transparency Campaign Against China (How the Philippines Rewrote the Counter Gray Zone Playbook). This report urged the Philippine government to adopt “assertive transparency” as a national policy, arguing that concentrated and proactive information dissemination would garner multilateral and international support while imposing reputational costs on China.

In 2023, Stratbase ADR also released another report titled The West Philippine Sea and the Convergence of Offensive Cyber and Disinformation Activities. This study catalogued what it described as China’s “false narratives” on the South China Sea and recommended that Manila pursue a “counter-narrative” strategy. It proposed framing China’s actions through nontraditional lenses such as the blue economy, environmental protection, fishermen’s livelihoods, and maritime security. The Philippines’ subsequent use of environmental issues as a cover for its “deception strategy” around features such as Scarborough Shoal, Sabina Shoal, and Iroquois Reef closely mirrored the report’s design.

Stratbase ADR Institute is one of the few Philippines think tanks that places the South China Sea at the center of its research agenda. Its founder, Albert del Rosario, is the former foreign minister who initiated the Philippines’ arbitration case on the South China Sea. The institute’s board of directors includes Benjamin Philip Romualdez, the brother of the Speaker of the House of Representatives, as well as prominent business elites with close ties to the government such as Manuel V. Pangilinan, Edgardo G. Lacson, and Ernest Z. Bower. As the initiator of the arbitration case, del Rosario represents the traditional “right wing” within the Philippines’ South China Sea policy community, and Stratbase ADR reflects this orientation with its nationalist, pro-American, and hardline ideological stance. Leveraging its extensive connections with the Marcos administration, the institute continually submits research findings and policy recommendations on the South China Sea to decision-making bodies, thereby serving as the intellectual engine driving the increasingly extreme tendencies of Philippine policy.

III. Trends and Challenges: The Future of the Philippines’ New Course on the South China Sea

Although a change of administration may bring some shifts in the preferences underpinning the Philippines’ South China Sea policy, the persistent reverberations of the arbitral award, the proliferation of domestic legislation, and the consolidation of political power structures have created a form of path dependence in this increasingly “radicalized” trajectory. This path dependence represents a “window of opportunity” for the Marcos administration and any future government that seeks to perpetuate his policy line on the South China Sea. Yet, there is no doubt that, compared with the Duterte administration’s pragmatism, flexibility, and adaptability, this “radicalized” tendency heightens the risks of “rigidity” and “vulnerability” in Manila’s approach to the South China Sea.

A. Path Dependence: The Structural Influence of Three Forces

In fact, the “radicalizing” shift in the Philippines’ South China Sea policy did not originate with the Marcos administration; it had already emerged during the Aquino III government. At that time, Manila abandoned its previous policy line and instead pursued a new set of measures: appealing for U.S. protection, resorting to legal arbitration, attempting to forge a so-called “coalition of claimant states,” and reinforcing its position at Second Thomas Shoal. These moves pushed China-Philippine relations to their lowest point in decades. When Duterte assumed office, the rightward “radicalization” of Philippine policy slowed and, in certain areas, even reversed. His administration adopted pragmatic steps such as reopening bilateral consultation mechanisms with China, launching joint oil and gas development initiatives, and building cooperative frameworks in fisheries and law enforcement. Duterte was able to curb the “rightward tilt” of policy partly because of his strong personal leadership style and tight control over domestic politics, and partly because the unilateralism and protectionism of the Trump administration had eroded allied confidence in the United States. Moreover, the arbitral award had just been issued on July 12, 2016, and its negative repercussions were only beginning to surface, which in turn somewhat reduced the pressure confronting Duterte’s government.

By contrast, the Marcos administration and its successors face an internal and external environment of far greater complexity. The comprehensive diffusion of the arbitral award, Washington’s renewed emphasis on alliances and partnerships, and the entrenched strength of domestic “right-wing” forces on South China Sea issues together reinforce a path-dependent trajectory of “radicalization.” This means that the strategic orientation of Philippine policy is unlikely to shift fundamentally with mere changes in political leadership.

1. The Diffusion and Penetration Effects of the Arbitral Award

Since the arbitral award was issued on July 12, 2016, its influence within the Philippines has unfolded in three distinct phases. The first phase (2016–2022) was characterized by diplomatic and public-opinion mobilization. Although the Duterte administration was reluctant to let the South China Sea issue undermine bilateral relations with China, it nevertheless devoted considerable effort to highlighting and publicizing the award. Through diplomatic statements as well as the efforts of domestic media outlets, politicians, and academic institutions, the Philippine government consistently underscored and disseminated the award, attempting to familiarize both domestic and international audiences with its content. The second phase (2023–2024) involved the “concretization” of the award through systematic unilateral maritime actions. The Marcos administration began to invoke the award openly as justification for unilateral operations at Second Thomas Shoal, Sabina Shoal, Scarborough Shoal, Iroquois Reef, and other contested features. The third phase (2024–present) has seen the award become embedded in Philippine legislation and national South China Sea policy. Manila has advanced this process through measures such as producing educational materials, submitting resolutions to the United Nations General Assembly, institutionalizing unilateral mechanisms, and initiating new arbitration cases. In this manner, the award has been internalized across multiple domains—including cognitive warfare, diplomacy, frontline operations, and legal contests—and elevated into a basic principle guiding all Philippine decision-making on the South China Sea.

Horizontally, therefore, the arbitral award has expanded from diplomacy into other domains such as maritime operations and information warfare. Vertically, it has penetrated into virtually every dimension of subsequent China-Philippine interactions over South China Sea disputes. Each Philippine decision and action on the issue now takes the award as a normative baseline. The award has thus been internalized not merely as a matter of national diplomacy but as a component of Philippine political life across different social strata. Decision-makers and elites treat it as a fundamental principle, and ordinary citizens regard it as self-evident. In July 2024, the independent polling organization Pulse Asia released survey results indicating that, among 1,200 respondents, 33 percent supported submitting a resolution to the United Nations General Assembly to secure majority backing and compel China to comply with the 2016 arbitral award. This means that more than one-third of the Philippine public upholds the award. Such “political correctness” narrows the government’s room for maneuver on South China Sea policy. Whether in power or in opposition, whether among elites or the general public, actors across the political spectrum must uphold the validity of the arbitral award or risk criticism and attacks from their rivals.

2. Consolidating the Framework of Philippine South China Sea Policy through Domestic Legislation

If the arbitral award provides the Philippine Department of Foreign Affairs with a legal basis for unilateral diplomatic claims over contested maritime zones, then the actions of the coast guard, navy, Bureau of Fisheries and Aquatic Resources, and fishing vessels around Scarborough Shoal and the Spratly Islands require domestic law as their foundation. For this reason, members of both the House of Representatives and the Senate began introducing the Philippine Maritime Zones Act during the Duterte administration. The objective was to internalize the arbitral award into Philippine domestic legislation by clarifying the geographic scope of jurisdictional claims and the boundaries of national rights in areas including the South China Sea. Before Marcos took office, the bill passed multiple times in the House but repeatedly stalled in the Senate. Since 2023, however, both chambers have accelerated the legislative process. As of September 2024, the bill has been deliberated upon and passed by both houses of Congress.

According to official data, the Philippine Maritime Zones Act explicitly delineates the scope of Manila’s claims in the South China Sea, including Scarborough Shoal and the so-called “Kalayaan Island Group.” It further seeks to designate all artificial installations within the Philippines claimed exclusive economic zone as Philippine territory. Once in force, the act will require the coast guard, navy, and other government vessels to patrol, enforce law, and undertake operations in disputed waters, regardless of how the international community interprets the arbitral award or whether Western states continue to support Manila’s position. In other words, the Maritime Zones Act not only incorporates the arbitral award into the domestic legal system but also codifies obligations, responsibilities, and rights for future Philippine governments in their maritime operations.

3. The Entrenchment of “Right-Wing” Forces on South China Sea Issues

Changes in the presidency or in congressional composition may alter the preferences of the political leadership, yet the Philippines has already developed relatively stable “right-wing” clusters of think tanks and media institutions. At the same time, the armed forces, coast guard, and judicial community are backed by powerful opposition families as well as the dual support of the United States and its Western partners. This “rightward” inclination among the elite is further reinforced by the majority of ordinary citizens. Surveys conducted at various intervals by the independent polling agency OCTA Research indicate that more than 60 percent of respondents hope the Marcos administration will increase naval patrols and troop deployments in the South China Sea, thereby asserting Philippine territorial rights through military measures. A July 2024 survey revealed that 54 percent of Filipino adults supported strengthening and expanding the U.S.–Philippine military relationship as a means of addressing territorial disputes in the West Philippine Sea, while only 11 percent expressed opposition. Among the three major “right-wing” political groupings, the family-based political clans may fluctuate, but right-oriented bureaucratic and elite factions have already secured their place in the Philippine political arena. With public opinion favoring tougher measures and Western support firmly behind them, their influence will remain entrenched for the long term.

By contrast, “left-wing” forces on South China Sea issues remain fragmented, confined to certain political families and limited social groups. Because the South China Sea has become a “politically correct” issue, “left-wing” voices of moderation are treated as pariahs. For instance, the Arroyo administration once promoted trilateral seismic surveys at Reed Bank involving China, the Philippines, and Vietnam, but the initiative was abandoned under threat of impeachment from the opposition. Duterte, both during his presidency and after leaving office, similarly became the target of relentless attacks from political rivals.

As a result, the “right-wing” holds a decisive advantage while “left-wing” statements of moderation remain faint or silenced. This configuration of domestic political forces compels any administration seeking to consolidate its power to adopt a “right-wing” orientation on South China Sea policy. If the president and his policymaking team can maintain some balance, the trajectory of “radicalization” may be moderated. However, if another “right-wing” presidential team emerges, the Philippines’ tilt toward “radicalization” in its South China Sea policy is likely to deepen further.

B. Challenges: The Combined Effect of Rigidity and Fragility

Under ideal conditions, when viewed solely through the lens of the South China Sea issue, the tendency toward policy “radicalization” easily produces path dependence. Except for a few pragmatic dissenting voices, it encounters relatively limited internal and external resistance. However, the Philippines’ South China Sea policy does not exist in isolation; rather, it is closely intertwined with its relations with Southeast Asian neighbors as well as with the United States and China. The “radicalized” orientation implies a lack of flexibility and resilience—manifesting both rigidity and fragility—which severely constrains the Philippines’ ability to maneuver between China, the United States, and ASEAN states, to extract concessions from both sides, and to maintain a balanced foreign policy. This will have profound repercussions on its external relations: the room for adjustment in bilateral ties with China will be squeezed, the Philippines–U.S. relationship will be tested by the South China Sea issue, and its relations with ASEAN countries are also likely to suffer setbacks as a result of Manila’s “radicalized” approach.

1. Geopolitical Risks to China–Philippines Economic Cooperation

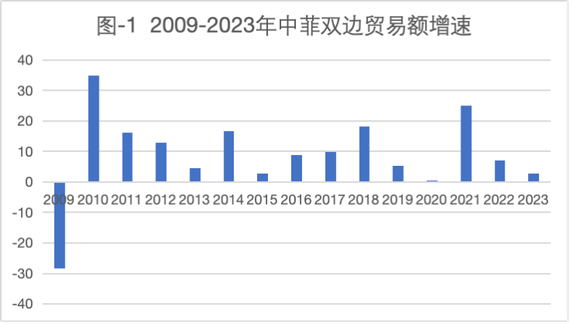

China occupies a significant—though not dominant—position in the Philippines’ external relations, serving for many years as its largest trading partner. The two countries share geographical proximity and deep historical and cultural ties. Although China–Philippines relations have experienced ups and downs, bilateral trade has consistently expanded: from merely 72.2 million USD at the establishment of diplomatic relations in 1975 to 71.9 billion USD in recent years. Since 2017, China has overtaken Japan to remain the Philippines’ top trading partner for seven consecutive years. China is also a key source of foreign direct investment. According to incomplete statistics, from 2016 to 2023, Chinese cumulative contracted investment in the Philippines reached 16.47 billion USD—accounting for 10 percent of the country’s total FDI inflows during the same period—covering critical sectors such as energy, agriculture, infrastructure, and cultural and people-to-people projects. In addition, there are approximately 1.5 million overseas Chinese residing in the Philippines, who hold a crucial position in the country’s economic landscape.