Dr. Rory Costello is an Associate Professor in the Department of Politics & Public Administration at the University of Limerick. He is Director of WhichCandidate.ie and is a member of the Management Board of the National Election and Democracy Study.

Across many developed countries, women have tended to be more left-leaning than men for several decades now (e.g. Inglehart and Norris 2000). However, a particularly wide gender gap in political attitudes is thought to be opening up among young people today. This is attributed to the fact that (as an article in the Financial Times put it) ‘young men and women now increasingly inhabit separate spaces and experience separate cultures’, particularly online. The #MeToo movement is thought to have contributed to rise of more strongly feminist views among young women, while the growth of the ‘manosphere’ and the popularity of male influencers such as Andrew Tate has pushed many young men to the right. Across a range of cultural issues – such as gender diversity and gender equality, multiculturalism and immigration, free speech versus hate speech – the political gender gap is said to be growing among the young. (See here for a nice overview of the debate on this issue, including some dissenting views).

Do these patterns apply in Ireland? Below, I present some evidence from a very large online survey that was carried during the recent election campaign. The survey comes from the voting aid application WhichCandidate.ie, which included questions on a wide range of policy issues, including many of the issues referred to above. During the final week of the election campaign, people who visited the website were invited to complete a survey asking about their demographic characteristics and voting preferences. In total, 115,000 people completed this demographic survey, which represents just over half of the people who used the website that week. In the figures below, the sample has been weighted to be representative of the population in terms of age, education, gender, location and home ownership.

Attitudes on cultural issues

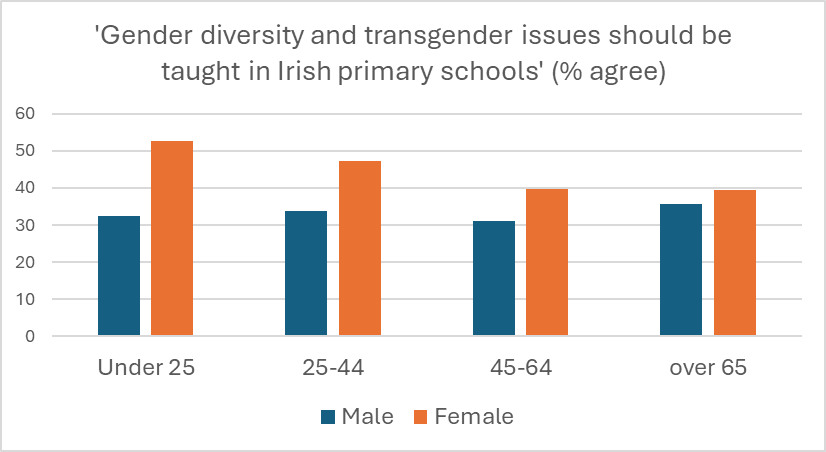

Attitudes of men and women on four issues that have been linked to the so-called ‘culture-wars’ are examined. There are slightly different age and gender patterns depending on the specific issue, but in all cases the gap between men and women is largest for the youngest cohort.

The first two issues shown below relate to gender: the teaching of gender diversity and transgender issues in schools; and political gender quotas. As shown below, the attitudes of men are relatively similar across age groups on both of these issues, while young women are considerably more progressive than older women. This results in a very large (20 point) gap between men and women in the youngest cohort on both issues.

Next, two issues that received a lot of attention in Ireland (particularly online) in recent years are examined: the abandoned hate speech legislation and accommodation for asylum seekers. For these issues, there is no linear age pattern for women, but there is for men: young men are actually less progressive than older men. This is consistent with the argument that young men are increasingly exposed to right-wing influencers online on cultural issues. Again, these patterns mean that the gender gap is biggest for the youngest cohort, where there is a 30 point difference for the hate speech issue and a 16 point difference for the asylum seeker issue.

Similar patterns are found on other issues linked to the so-called culture wars (such as abortion), whereby the gender gap is biggest among the young. However, the same is not true for economic issues, where the gender gap is relatively stable across age groups.

Party preferences

Are these differences in attitudes between young men and women reflected in how they vote? Respondents to the survey were asked to indicate who they intended to give their first preference vote to in the election. The figures below show the percentage of respondents who intended to vote for a party associated with conservative or right-wing positions on cultural issues (i.e., Aontú, Independent Ireland, plus the various far-right parties – the National Party, Irish Freedom Party, Irish People and Ireland First).

Again, the gender gap is biggest for the youngest voters. While relatively few respondents intended to vote for one of these parties, the figure was noticeably higher among young men (8%) than young women (3%). The gap between men and women tails off for the older cohorts.

Given the relatively marginal place of these parties in the Irish political landscape, which can be a disincentive for people to vote for them, it is perhaps more revealing to look at attitudes to these parties rather than voting intentions. Respondents were asked to indicate which party or parties they particularly disliked and would never vote for. The figures below show the percentage of respondents who indicated that they would never vote for one of the culturally conservative parties listed above. 61% of young women in the sample said they would never vote for one or more of these parties, compared to 48% of young men. This indicates that the potential support base for culturally conservative parties is higher among young men, even if relatively few of them voted for one of these parties this time out. (Interestingly, Aontú is particularly unpopular among young women – it is by far the most disliked party among this group).

Conclusion

The evidence presented here suggests that there is a noticeable difference in the political attitudes of young men and women on cultural issues. Across all of the cultural issues examined, young men are found to have far more conservative views than young women, and this gender gap is much smaller for older age groups. These differences were also found in relation to political preferences, with young women particularly opposed to parties associated with culturally conservative policy positions.

Similar patterns can be observed in other surveys. For example, the National Election and Democracy Study asked survey respondents at the time of the Family and Care referendums whether they considered themselves to be a feminist. The biggest gap was between young men and young women; and while young women were more likely to describe themselves as a feminist than older women, young men were less likely to describe themselves as feminist than older men (echoing similar findings in the UK).

All of this suggests that Ireland has not escaped a trend that appears to have emerged internationally, with a growing Gen-Z gender gap in political attitudes. More in-depth research is needed to corroborate these findings, to see how this has evolved over time, and to test if these patterns are indeed driven by social media consumption, as some have speculated.

politicalreform.ie (Article Sourced Website)

#gender #divide #young #peoples #political #opinions #Ireland