It’s not hard to see why Europeans often feel a sense of superiority over Americans.

No European city has an area as dangerous or decrepit as San Francisco’s Tenderloin district. Some Americans obsess about Europe’s supposedly no-go areas, but no European city has crime on par with places like Memphis, Tennessee, or St. Louis, Missouri. In 2023, more people were murdered in Chicago (population: 2.7 million) than in all of Italy (population: 59 million). When you ride New York’s subways, it’s best not to wear nice shoes in case you step in a pool of vomit.

Our cities are not just vastly safer than America’s: They’re more beautiful, more vibrant with history and art and food. Europe has the Tuscan countryside, the Swiss Alps, Barcelona, Provence, the French Riviera, and the Balearic Islands, all inside an area smaller than Texas.

Europe may be beautiful, but it has become a byword for economic malaise—a land of snooty Europoors who prostrate themselves before a disdainful President Donald Trump because they aren’t sure they can defend themselves from Russian aggression.

Most of us in Europe don’t own ice makers. It can get very hot during our summers, but air conditioning is still a luxury across the continent. An American friend visiting my house in London was bewildered to see me hanging my clothes up to dry on a metal hanger in my hallway: Like most Europeans, I don’t own a dryer.

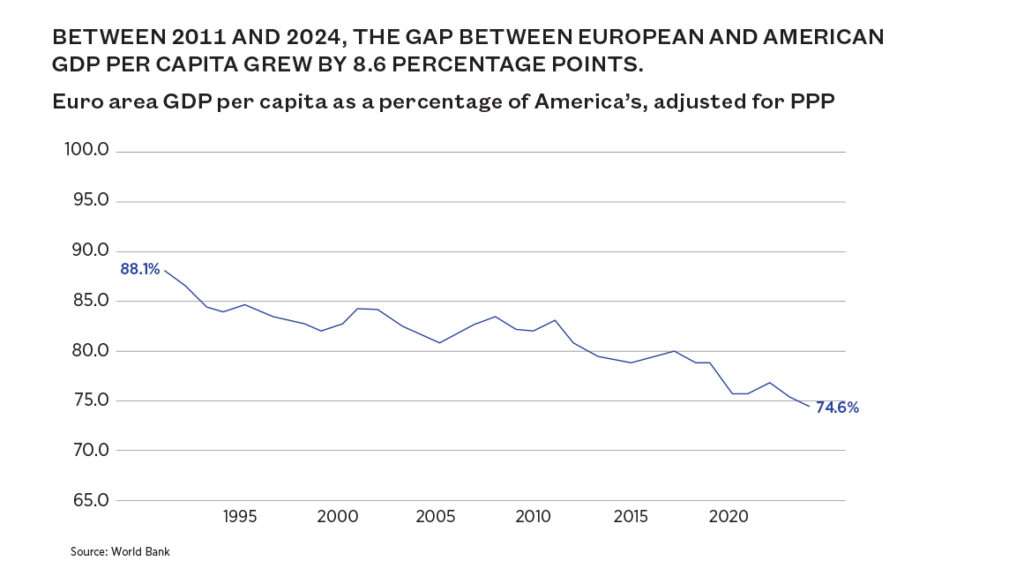

The average American could stop working in the first week of October and still will have earned more than the average Frenchman working until the end of the year. In Western Europe, GDP per capita—the average economic output per person—is about $63,000 per year, adjusted for the cost of living. In the United States, it is $86,000.

Yes, Europeans work fewer hours and take more vacation. But that explains only part of the gap.

For roughly two decades, Western Europe, home to the continent’s largest economies, has stagnated. In 1995, its labor productivity—the value of goods and services produced per hour worked—was 95 percent of what it was in the United States, having risen from just 22 percent in 1945. By 2023, it was down to 80 percent. Ten years ago, 52 of the world’s top 100 companies by market capitalization were American and 28 were European. Since then, the American total has grown to 58 while the European count has fallen to 18. The United States has produced five companies worth more than $2 trillion. At around $350 billion, Europe’s largest company, the enterprise software provider SAP, is worth about as much as Home Depot.

Many Europeans assume their lower incomes are the price they pay for ensuring their poorer countrymen have better living standards. But the median American household has a disposable income that is 16 percent higher than the median German household, adjusted for purchasing power. Only the poorest 10 percent of Americans do worse than their French, German, or Italian counterparts in terms of disposable income, which factors in taxes and welfare.

What explains this gap between Europe and the U.S.? There are many factors, from rigid labor markets to energy restrictions to trade barriers to burdensome regulations on tech companies. The connecting thread is that Europe is poor because of specific policy choices. Europe is poor because it chose to be poor.

Europe’s most obvious failure is its tech sector. By nearly every measure it lags behind America’s, in an era in which technological progress is one of the strongest drivers of material well-being. Yet rather than try to emulate America’s relatively hands-off approach, which has given its entrepreneurs, inventors, and investors the freedom to build such companies as Apple, Tesla, Microsoft, and Google, the European Union (E.U.) is known as a “regulatory superpower.”

In recent years, the E.U. has imposed expansive new regulations on data privacy, which enshrined in law the cookie banners that now litter the internet, and has plunged into the preemptive regulation of artificial intelligence, which its internal market commissioner claimed would allow European “startups and researchers to lead the global race for trustworthy AI.”

Europe has some of the highest electricity prices on Earth, thanks to environmental laws and an overreliance on imported gas—a huge problem when AI relies on power-hungry data centers. But never fear: Electronic devices in the E.U. must be fitted with a USB-C port, eliminating a grand total of 2 grams of waste per citizen per year.

E.U. leaders insist this is actually America’s fault. European officialdom spent much of the 2010s blaming its tech sector’s sluggishness on unfair practices by American tech companies. One official even compared U.S. tech companies to a soccer team that trapped its opponents in their dressing room: “Someone has locked it and thrown away the key.”

Their answer, inevitably, was even more regulation. In 2022, the E.U. passed blockbuster legislation to regulate platforms like Google and Amazon. This, it said, would “create new opportunities for startups.”

It didn’t work. Two months later, OpenAI, an American startup with no previous consumer products, launched ChatGPT. A few months after that, Anthropic and Google followed with their offerings. (Google’s DeepMind is based in London, but Google bought it in 2014.) Here was a digital market where success could not reasonably be attributed to incumbency, yet European companies were still on the fringes.

Europe has missed out on wave after wave of frontier technology not because of American mischief, but because the continent has allowed its labor markets, energy costs, trade policy, and capital markets to go awry.

Belgium, home to the E.U.’s capital city of Brussels, is famous for having survived without a formal, permanent federal government. It went 652 days with an interim government until a new federal government was formed in 2020. A decade earlier, in 2010, it went 589 days before a government was finally formed. A caretaker administration sat in power during these periods, keeping the machinery of the state operating but unable to pass any new laws, spending, or tax reforms.

Yet life went on. Belgians who got sick were still covered by the country’s universal health insurance system. Belgians turning 65 still retired into a generous pension, pegged to whatever they had earned during their working lives. The trains kept running, and crime stayed low.

Though the country was rocked by bank failures in 2008–2009 and the wider eurozone debt crisis that followed the Great Recession, life has not become radically different for ordinary people over these years. Taxes and government spending are slowly rising, and GDP growth was an anemic 0.6 percent per year from 2007 through 2023 (half of the rate in the U.S.). As in many European countries, issues like immigration and Islam got more attention than the country’s underlying economic and political sclerosis.

It may be tempting to conclude that Europeans are simply less culturally inclined toward economic dynamism and growth. Maybe a quiet life is all that Europeans really want.

But this argument is unconvincing. There are, after all, plenty of European tech founders. They just live in America. One in 10 U.S. tech startups is founded by a European, and that share has risen over the past 10 years.

It is also hard to square this argument with Europe’s history. Brussels is less than half an hour from the cradle of modern capitalism. The old towns of Ghent and Bruges are nearly perfectly preserved from their late medieval heyday, when they were at the crossroads of Europe’s wool and cloth trade. The world’s first stock exchange still stands in Bruges. Nearby Antwerp was the capital of global trade and finance in the 16th century, when modern capitalism really started to flower. In the 19th century, Belgium industrialized earlier and faster than the United States, building powerful coal, iron, textile and railway industries, and leading the way out of poverty and hunger. Europe, historically, has had no shortage of entrepreneurs and capitalists.

So why do companies struggle to innovate in Europe today? Pieter Garicano, author of the Silicon Continent newsletter, has suggested that what really separates European companies from American ones is Europe’s high cost of business failure, rooted in its inflexible labor laws.

Each country’s rules are different. But they tend to protect workers from being fired, require union agreement for mass layoffs, and demand large payouts for those who do lose their jobs. These are more than just the cost of doing business. In markets where companies have to take risks, mass layoffs can be unavoidable. But in the United States, layoffs are usually quick and relatively low-cost; in the E.U., they can take months or even years.

Turnover is thus much higher in America. About 1 percent of the U.S. work force is laid off every month, whereas in Germany, less than 0.1 percent is. That makes the cost of risk-taking much higher in Europe than in the United States. American companies can treat layoffs as a normal if regrettable part of the trial-and-error process. For European companies, the difficulty of shutting down company divisions when strategic bets turn out not to have paid off makes it much more costly to take those bets to begin with.

For larger companies, this can make it far harder to change approach than their rivals elsewhere find it. Volkswagen, Europe’s largest company by revenue, faces an enormous threat from inexpensive Chinese electric vehicles, yet its attempts to restructure were drawn out for more than a year by union objections to factory closures, which the company eventually gave in to. When SAP laid off 10,000 workers, it reportedly had to pay out three years’ worth of salary to each of the European employees it wanted to let go.

Smaller companies are often exempted from these rules. But that makes little difference, because every ambitious little startup hopes to one day become a big one, and plans accordingly. The prospect of being captured by these labor laws once they have grown puts them off from setting up in Europe. It also deters venture capital investors.

Not every European state has such restrictive labor laws. Denmark, for example, pairs generous unemployment insurance with flexible rules about hiring and firing, a model known as “flexicurity.” Sweden’s are also much less rigid than those in most of Western Europe. These countries are among the richest in Europe. Denmark is one of the few European nations that approaches America’s GDP per capita adjusted for purchasing power, and it has one of the continent’s highest levels of employment.

These countries also punch well above their weight in high tech. Denmark’s Novo Nordisk, which has pioneered the use of GLP-1 drugs to help with weight loss, has become one of Europe’s biggest companies. Sweden’s Spotify is one of Europe’s only successful consumer technology platforms.

Rigid labor market laws have another drawback. The more difficult it is to hire and fire workers, the harder immigrants tend to find it to assimilate into their new country’s job market—and the more they resort to low-paid informal work that they can get through social and family connections. This reduces how much exposure they get to people from their new country’s native population, which makes them less likely to adjust to, and adopt, the country’s values. When combined with generous welfare benefits, that also makes it easier to keep women at home instead of working, which further limits cultural integration. More flexible labor market laws might not just add vitality to Europe’s economies; they could help address one of the continent’s biggest social problems.

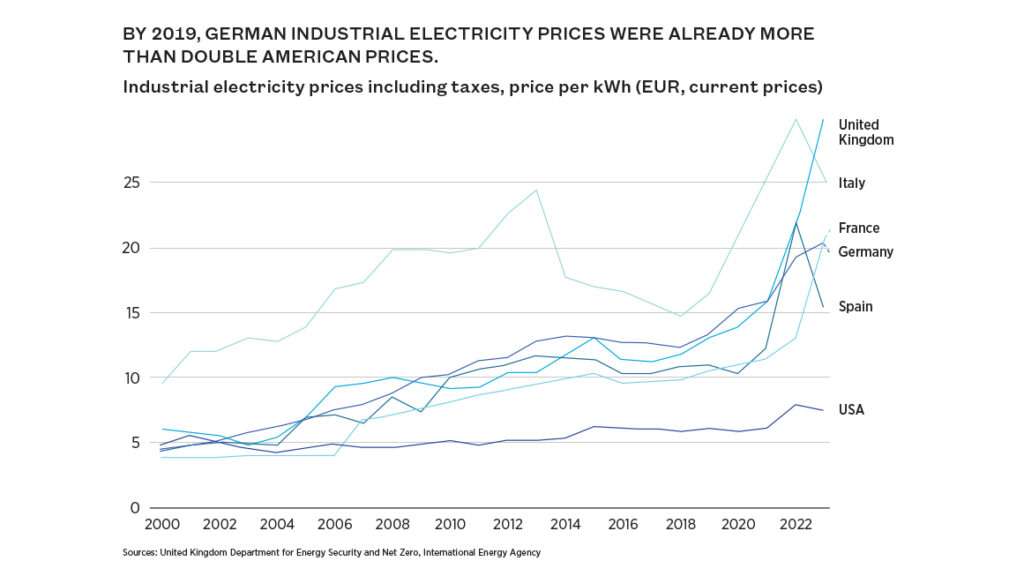

In 2003, energy prices in America and in Europe’s largest economies were similar. But by 2021—before Russia’s invasion of Ukraine sent European energy prices even higher—German industrial electricity prices were 156 percent of what American industrial users were paying. Spanish industrial customers were paying twice the American price. In 2021, Italian businesses, who have long faced high prices, paid four times as much for electricity as American ones. In Europe’s largest economies, energy prices were nearly twice as high as American prices before the Ukraine war.

The price of natural gas has shot up since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, driving energy costs even higher. One in 10 Europeans reported not being able to keep their homes warm enough during the winter of 2023. In 2022, when energy prices were at their highest, factories across the continent were forced to furlough their workers and pause production.

But it is a mistake to blame Europe’s energy problems solely on the war, as some do. Natural gas was cheap during the 2010s: lower in nominal terms in 2015 than it had been 10 years earlier, and falling even more by the end of the decade. But even as gas prices fell, electricity prices rose.

The biggest reason is probably climate policy. European governments and the E.U. have committed the continent to an exceptionally demanding decarbonization schedule that runs far ahead of those of the United States or China. By 2030, European emissions must be at least 55 percent below where they were in 1990. National governments that do not act to bring this about can be prosecuted.

Compare this to America, which merely seeks a nonbinding 50 percent to 52 percent reduction in emissions below its 2005 peak, which was higher than in 1990. China doesn’t even plan for emissions to start falling until after 2030. Europe adopted a carbon pricing system in 2005. It now charges about six times more per ton of carbon than China does, and about 50 percent more than California. Most U.S. states do not price carbon emissions at all.

From 2000 to 2020, European countries cut their coal use by more than half, and from 2010 to 2021 they shut down 80 gigawatts’ worth of coal-fired power plants. Along with gas, most of the shortfall was made up by wind and solar, both of which are significantly subsidized by levies on energy bills.

Many European states have responded to these high prices by subsidizing electricity for large users. As well as raising costs for other energy users, this has the effect of making it harder for smaller companies to compete with their larger rivals. Since such policies are unlikely to be sustainable for very long, they do little to keep these sectors going in the long run. The continued investment and entry they require depends on returns over a long time horizon.

High energy costs have led to rolling sectoral recessions. A recent report into European competitiveness by former Italian Prime Minister Mario Draghi estimated that output in Europe’s four largest energy-intensive sectors—chemicals, basic metals, minerals, and paper—has fallen by over 10 percent in the past four years, following the rise in gas prices since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. It will cost half a trillion euros to decarbonize just these sectors. Decarbonizing shipping and aviation will cost a further 100 billion euros per year.

Yet Europe’s leaders have generally refused to accept that its green energy policies are this costly. Even the Draghi report, held by many to be the first serious attempt to acknowledge the continent’s economic problems, claims that decarbonization is an opportunity “to take the lead in new clean technologies and circularity solutions.” But Europe’s eagerness to take the lead on decarbonization is the source of many of its troubles.

If Europe’s problems were limited to national policy errors, then in time you would expect economic activity to flow to islands of relative openness, such as Sweden and Denmark, just as bad policies in California and New York have driven people to Florida and Texas.

That might even be how the E.U. is supposed to work. Its single market is often seen as the E.U.’s crowning achievement: a set of rules that are supposed to ensure the frictionless movement of goods, services, capital, and people across the borders of Europe’s member states.

But Luis Garicano, an economist and former member of European Parliament, argues that the single market has been left to decay—and sometimes has actually become a barrier to trade by adding new regulations on top of existing ones.

The General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), a sweeping law governing data use and privacy, is interpreted and enforced differently in each member state. In practice, this means that compliance with the law varies wildly across the bloc. Ireland, for example, approved Meta’s data protection practices. But German and French GDPR regulators disagreed and levied fines of 390 million euros on the company. New antitrust powers introduced to govern Big Tech companies have been layered on top of national-level antitrust enforcement, creating multiple enforcers and contradictory sets of rules for the same conduct.

This pattern repeats itself for every other flagship E.U. regulation, and is built into the design of the new AI Act. In total, the Union now has 270 different technology regulators. The Draghi report estimates the direct costs of rules being duplicated like this is some 200 billion euros per year.

In other cases, the single market has simply been left unfinished. Professional qualifications, for example, are not recognized across European borders—when engineers based in Portugal win a contract for work in Germany, they face lengthy bureaucratic “equivalency checks” that stop them in practice from performing the work. National environmental regulations block products that are safely produced and used across the rest of the continent. Many important sectors, like finance and energy, are excluded from the single market altogether.

The number of lawsuits brought against governments for single market infringements—the bread and butter of enforcing European free trade—has collapsed under the E.U.’s current leadership. Thierry Breton, who was internal market commissioner until last year, was supposed to work on breaking down these trade barriers but focused instead on fights with U.S. tech CEOs and stewarding the continent’s AI regulations.

This is hugely significant for Europe’s economy. Trade within the E.U. is vast, and making it even slightly easier could have enormous benefits. The International Monetary Fund estimates that barriers to trade within the E.U. are equivalent to a 44 percent tariff on goods and a 110 percent tariff on services. According to Isabelle Mateos y Lago, chief economist of the French bank BNP Paribas, “it would only take a 2.4 per cent increase in intra-EU trade to make up for a 20 per cent fall in exports to the US.”

This might also be a reason Europe’s tech companies have struggled: Unlike their American or Chinese rivals, they do not have a large domestic market to sell into.

The solution is simple. Rather than trying to harmonize regulations with a single rule book written in Brussels, trust that rules that are good enough for Swedish consumers are acceptable for Spanish ones too. If something is legal in one European country, you should be able to trade it and use it in all the others, provided it is clear where it comes from. “Mutual recognition” of this kind was supposed to be the basis of the single market. Restoring it would be one of the biggest trade liberalizations in world history.

For all of Europe’s longrunning economic problems, it was only after the Great Recession that the continent’s economy really began to flatline. Meanwhile, America’s recovered and continued to grow.

What accounts for this sharp difference in performance? Tyler Goodspeed, former acting chair of the U.S. Council of Economic Advisers, points to the Basel III financial regulations, global rules set out after the 2008 financial crisis. These were intended to reduce the risk of a future financial crisis by curbing lending to businesses and requiring banks to hold more “safe” assets.

Whether these measures actually increase financial stability is questionable, given that earlier iterations required banks to hold more mortgage debt than they wanted. With the Great Recession, that came to look like a mistake.

Though the postcrisis Basel rules were adopted in the United States as well, their effect in Europe may have been particularly chilling for business lending. There are two reasons for that.

One: Europe’s banking system is much more consolidated than America’s. The United States has thousands of smaller banks, which escape many of the strictest rules. European countries tend to be dominated by only a handful of much larger institutions.

Two: Europe’s businesses are far more dependent on bank lending for financing than America’s are. In Europe, 68 percent of business financing comes from banks, compared to just 20 percent in the United States. America’s much larger venture capital, private equity, and pension fund investors make restrictions on bank lending much less important than in Europe.

Debt financing generally favors capital-intensive businesses, such as Sweden’s H2 Green Steel, which raised 4.2 billion euros in debt last year to finance a hydrogen-fired steel mill. Software-based companies, which have little collateral to borrow against, tend to find it harder to get loans this way.

This isn’t a problem in Silicon Valley, which has access to America’s $1.25 trillion in venture capital. If Goodspeed is right, Basel’s tighter rules on lending could be a big reason that European startups have struggled to grow compared to their American peers. Fixing the problem need not mean adding more risk to European finance: Removing barriers to the sort of investments that American companies can access could be the answer.

There are islands of success across the continent. The Dutch company ASML is the world’s only manufacturer of the photolithography machines needed to make advanced semiconductors. European companies do well in sectors such as luxury fashion, pharmaceuticals, cosmetics, and tourism. Many of the most celebrated video games of recent years, from Baldur’s Gate 3 to Clair Obscur: Expedition 33, were developed in Europe. Soccer is the world’s favorite sport, and Europe’s teams and leagues dominate it.

These are not sectors that win wars or excite advocates of industrial policy. But they are profitable, and they make our world better.

Though their economies are relatively small, the E.U.’s postcommunist members have grown impressively since joining the bloc in the early 2000s. Poland and Hungary’s GDPs per capita have more than doubled in real terms since 2000, though Hungary has stagnated in recent years. In Romania it has nearly tripled, though from a lower level after enduring a particularly evil and destructive communist regime. These states have their problems, but they also tend to be clearer-eyed about the need for economic dynamism than Western Europeans.

The world needs a rich, prosperous Europe. For all the region’s failings, private property rights and the rule of law are more strongly protected and cherished in Europe than in most states around the world. Those values are incredibly difficult to build where they do not exist. Compared to that, fixing a few of the most important elements of a continent’s economic policy should be easy.

Shifting Europeans away from Franco-German-style labor laws sounds impossible, but few Europeans fear the thought of being a bit more like Denmark. Combining decarbonization with energy abundance will become easier as nuclear, solar, and battery power get cheaper. Revitalizing the single market is a career-making project for an ambitious reformer. Less onerous financial regulation can be implemented without major political costs, especially when it means removing barriers to investment approaches that have worked well in America. Those changes won’t repair all of Europe’s problems—its welfare states, for example, would still need a significant overhaul to be solvent—but they could set the stage for further reforms.

Bringing this complacent continent back to reality will not be easy, but it can be done. Europe chose to be poor. But that also means it can choose not to be.

This article originally appeared in print under the headline “Why Europeans Have Less.”

reason.com (Article Sourced Website)

#Europoors #choosing #Americans #doesnt