Click here to listen to the Audio verison of this story!

The exporting of liquefied natural gas (LNG) has changed the game for producers of those molecules in every basin in recent years. The rising export demand, starting when LNG exports began in 2016, has helped raise natural gas from the $2 per million btu (MMBtu) doldrums they were in when they crashed to $1.95 per MMBtu in 2012. After peaking at $8.82 per MMBtu in August of 2022, prices had settled to a still decent $3.12 in May of 2025 at the Henry Hub, according to figures from the U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA).

In the Permian Basin, where natural gas is mostly a byproduct of oil production—and sometimes more of a nuisance than a product—the market price matters less than takeaway capacity. The exact destination matters little as long as there is one. The ancient options of flaring or simply venting are mostly gone, especially the latter. So, without sufficient gas takeaway capacity, entire wells could have to be shut down.

One challenge for takeaway capacity is that, as the Basin’s oil production matures, wells produce more and more gas every year, taxing the pipeline infrastructure. Most midstream carries gas south and eastward to the Gulf Coast—where LNG exports could be among its destinations.

Nikolay Filchev

Permian natural gas output is now approximately 22 Bcf/d, “a number that has been rising in recent years” due to the increasing gassiness of wells, said Nikolay Filchev, a member of the Americas Gas Team for S&P Global Commodity Insights. However, he added, actual production is even higher, as the 22 Bcf/d measures only what goes into pipelines. “This excludes gas used for local footprints such as wellhead gas used for e-fracs,” or for data centers, bitcoin mining, and more.

Exactly how much Permian Basin natural goes to LNG exports is impossible to track, he pointed out. That’s because “Permian Basin gas travels mostly on intrastate pipelines, where there is less regulation and tracking.”

Maria Sanchez

Maria Sanchez, Natural Gas Products and Senior Energy Analyst for Sugar Land-based Industrial Info Resources, explained further. “With the flow data/nominations, we observe close to 60 percent of the gas produced in the Permian Basin.” That’s in contrast to gas from the Appalachian regions, where the states are smaller and closer to 100 percent of natural gas goes interstate.

At the same time, there are ways to estimate what goes where. “Some Permian gas goes to the north—about 1 Bcf/d—to the west—New Mexico, Arizona, and California, about 3 Bcf/d—and to Mexico—1.7-1.9 Bcf/d,” Filchev said. “Some of the NM/AZ/CA gas also goes to Mexico, about 0.5 Bcf/d. About 14-15 Bcf/d goes to coastal markets and international trade. Two Texas LNG plants use 5 Bcf/d, and 75-80 percent of that is probably from the Permian.”

What goes directly to Mexico is about 4.5 Bcf/d, with about half of that coming from the Permian, that amount being the 1.7-1.9 Bcf/d cited earlier. Filchev related that in Louisiana some Permian-originated gas is mixed with gas from the Haynesville formation of East Texas and Northwest Louisiana—but how much Permian gas is in that mix is impossible to evaluate.

About half of the Permian’s recent growth is likely headed to LNG, Sanchez estimated. “I don’t have an exact percentage but would say over 50 percent of the Permian growth has gone to LNG,” she said. She bases that estimate on the following facts: “Between April of 2025 and January of 2019, Permian gas production increased by 12.3 Bcf/d. Exports to Mexico rose by 1.98 Bcf/d and LNG terminals in TX and LA by 11.12 Bcf/d. But Appalachian gas also found a home in LNG exports. That’s why some pipelines reversed flow and now move gas from the Northeast down to the Gulf.”

Henry Hub natural gas spot prices over the last 30 years?

LNG Growth

Demand for LNG feedstock has exploded since exports in 2016 started at zero. Today (April figures, down somewhat due to maintenance) the total is 16.4 Bcf/d, with SPGlobal expecting that to almost double, to 28 Bcf/d, by 2030. “Permian Basin gas will be a significant part of that number,” he said. Cheniere’s Sabine Pass LNG plant was the first to export LNG, Filchev said, with SPGlobal data showing a February 2016 first-export date for the facility located in Cameron Parish, La. It reached commercial operation in May of that year.

With the new administration promising to fast-track approvals of a variety of energy projects, including LNG facilities, will that further speed export capacity? Filchev pointed out that, “LNG capacity is set to rise this year anyway because several projects were already FID’d (final investment decision made) before the Biden moratoriums.” The moratoriums were instituted in 2024.

For example, the Woodside terminal in Lake Charles, La., is slated to come online in 2025, with a permitted capacity of 27.6 million Mtpa (million tons per annum). Woodside acquired the former Driftwood LNG project in 2024 when it bought Houston-based Tellurian.

Even with a more open permitting process, Filchev pointed out that FIDs and permitting are only parts of a larger process in building new terminals. “There is also the need for financing, and to verify demand.” For example, “If a company is relying on external financing, they must first line up off-takers.” This is similar to pipeline companies starting their planning by hosting an open season.

Lining them up then involves responding to global supply/demand markets. Then those off-takers themselves need somewhere to sell their LNG. “Worldwide supply and demand play a major part. We compete with Qatar, Canada, Australia, Africa for supply, but there are also demand limits.” The latter of which are a greater concern in the time of tariff wars.

“And there are layers to the tariffs—certain nations, including South Africa, are negotiating contracts for more offtake in order to address trade deficits and limit tariffs,” he continued.

The financing part is easier if a company can do it internally, by shifting some projects. “It is much simpler and does not invite investors to look over their shoulder,” said Filchev.

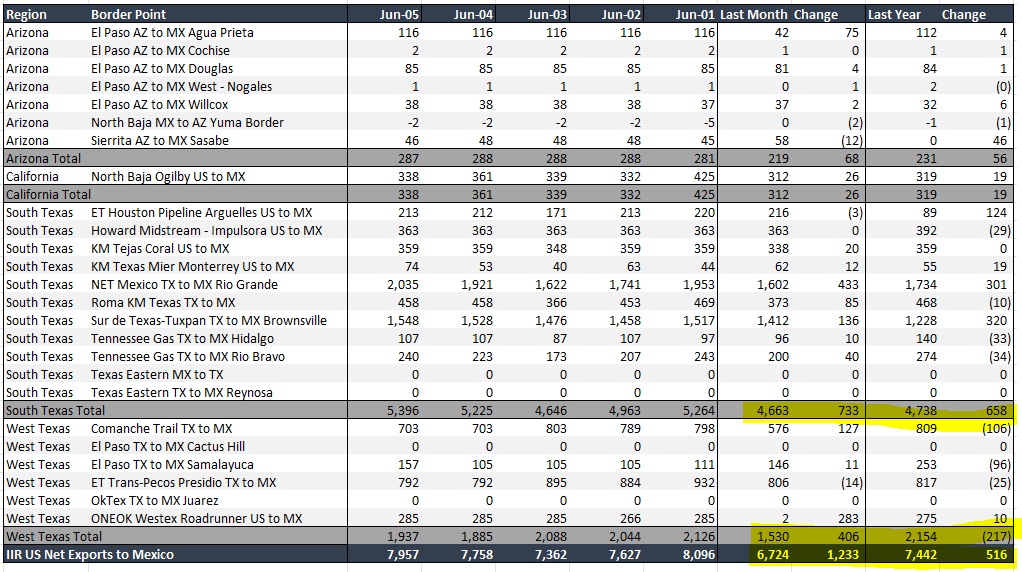

Surplus gas is a thing. This chart from Industrial Info Resources (IIR) shows how exports to Mexico have been increasing. What’s the point here? For one thing, the exports uptick is due largely to more gas being sent from West and South Texas.

Permian Takeaway Growth

As previously stated, getting Permian from wellhead to LNG facility may be the biggest key. SPGlobal is tracking several new pipelines planned by the end of 2026/early 2027, Filchev said.

Most new access will flow east toward the LNG terminals. “This summer we expect Matterhorn Express Pipeline to finish its compression [0.5 Bcf/d] and expand to its full nameplate capacity of 2.5 Bcf/d. The other projects in the outlook are Natural Gas Pipeline Co. of America [NGPL] Delaware Basin [October 2025, 0.05 Bcf/d], Northern Natural Gas Co. [NNG] Tarzan [0.09 Bcf/d], Transwestern Pipeline Co. LLC WT-0 [November 2026, 0.08 Bcf/d], Blackcomb Pipeline [July 2026, 2.5 Bcf/d], Gulf Coast Express Expansion [August 2026, 0.6 Bcf/d], and Hugh Brinson [January 2027, 1.5 Bcf/d].”

Turner Industries recently completed a fin fan replacement project on the first of six trains at Cheniere’s Sabine Pass LNG export facility in Cameron, La. Liquefaction is getting bigger all the time.

Hugh Brinson could be expanded to 2.2 Bcf/d, and there might be other projects coming up. So, depending on rig activity, which slowed during Q2 of 2025, and the amount of gas produced by new wells, this could be enough to keep up with production.

While there are occasions where supply exceeds capacity—with Waha hub prices going negative earlier this year—generally there’s a sort of leapfrog, back-and-forth game in supply vs takeaway. Said Sanchez, “The story with the Permian is that every time production outpaces takeaway capacity, as capacity is added, production grows more. Flaring is down because it is more restricted by regulation, but also because it’s less necessary. Economics are really good for gas—so as long as capacity is available, production will keep growing.”

She quoted EIA numbers showing the region adding more than 7 Bcf/d of new pipelines by 2028.

At this writing, in addition tariff negotiations, there were concerns that the Department of Commerce was beginning to require licenses for the export of ethane to China—and then limiting the issuance of those licenses. Depending on how all those negotiations play out, exports of natural gas and other products could be affected, either by the marketplace, by regulators, or both

And unlike plants that are purely or primarily natural gas like the Haynesville, Marcellus, and others, the price of natural gas has no influence on its production in the Permian. As long as oil is profitable and natural gas has an outlet, the latter keeps coming.

Paul Wiseman

A longtime contributor to PB Oil and Gas Magazine, Paul Wiseman is an energy industry freelance writer.

The post LNG Changes Everything appeared first on Permian Basin Oil and Gas Magazine.

pboilandgasmagazine.com (Article Sourced Website)

#LNG