What better way to enjoy Labor Day than sitting down three days beforehand and writing about Studs Terkel (1912-2008) — WPA writer, radio guy, oral historian, rabble-rouser, American — and his 1974 bestseller Working? It may have set some kind of record at the time for longest subtitle: People Talk About What They Do All Day and How They Feel About What They Do, which was conveniently exactly what the book was about.

I read Working sometime in college, during the Reagan administration, which certainly put an interesting contemporary spin on the interviews with ordinary Americans. In 1981, the genial old bastard fired striking air traffic controllers, which labor historian Erik Loomis called “probably the greatest disaster for organized labor in the history of American labor.” Labor has never since regained the strength it had gained in the postwar era.

August 3 In Labor History: Jolly Grandpa Ronald Reagan Crushes Air Traffic Controllers Union Like Ants

Why Do Planes Fall Down From The Sky Every Time Trump Walks By?

Here’s a surprise: Working includes interviews with an “airline reservationist” (a job that no longer quite exists, having been swallowed up by the broader category of “customer support”) and an “airline stewardess” (a job title that no longer exists, though the job does). But Terkel didn’t interview an air traffic controller or a pilot, which, given how nuts aviation has become these days, would have been worth having. Even more shocking, he didn’t interview any crypto traders.

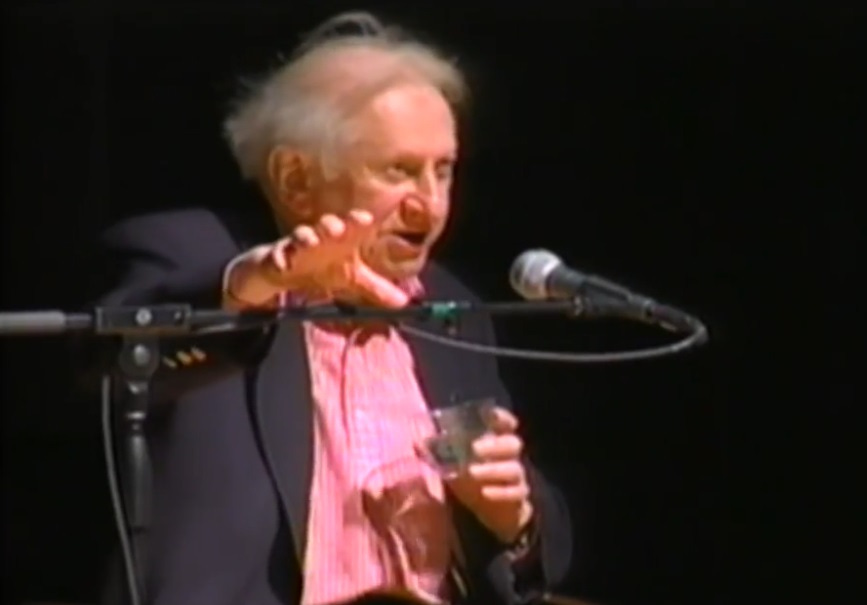

Anyway, today we will be celebrating Working class hero Studs Terkel, who would no doubt have some things to say about a mad king threatening to send troops to his beloved Chicago. Let’s start with this montage of Terkel telling the same story about Labor Day, on three, no, four different occasions between 1990 and 2003:

Every newspaper, he noted in a coda, has a “Business” section, but why isn’t there a “Labor” section, huh? And if you think for a moment, it dawns on you that, well duh, newspapers are (or were) a business, silly.

In his introductory essay for Working, Terkel explains that, because it’s about work, the book is also

about violence—to the spirit as well as to the body. It is about ulcers as well as accidents, about shouting matches as well as fistfights, about nervous breakdowns as well as kicking the dog around. It is, above all (or beneath all), about daily humiliations. To survive the day is triumph enough for the walking wounded among the great many of us

That’s the first damn paragraph, and the second paragraph suggests that the scars of all that violence “may have touched, malignantly, the soul of our society.” But just as you’re steeling yourself for a depressing read — and at times, it certainly is — Terkel adds that the book is more than just a chronicle of work grinding people down day after day:

It is about a search, too, for daily meaning as well as daily bread, for recognition as well as cash, for astonishment rather than torpor; in short, for a sort of life rather than a Monday through Friday sort of dying. Perhaps immortality, too, is part of the quest. To be remembered was the wish, spoken and unspoken, of the heroes and heroines of this book.

And that’s one of the things that has stuck with me since I first read Working, that duality, that search for meaning even in drudgework, and that sense of drudgery that can tinge even jobs that we love. I have my dream job, writing filthy jokes about politics for a living and sometimes even hearing from people that they remember some piece I wrote, and I wouldn’t trade it for anything. But there are mornings where I’d much rather stay in bed, even though it’s nothing like how I disliked waiting tables in college, or the nerve-wracking anxiety I felt when I was student-teaching an eighth-grade class. Some days, even the work you love is work.

I don’t remember when exactly I first read Working, but it was probably not long after PBS ran its 1982 adaptation of the 1977 Broadway musical. I haven’t been able to find the full “American Playhouse” program streaming, but I’m sure it’s out there somewhere.

But here’s a snippet that surfaced on YouTube, with Jennifer Warnes singing the James Taylor song “Millworker,” inspired by Terkel’s interview of Grace Clements, a “felter” in a luggage factory. (The same YouTube account also posted a clip of Rita Moreno as waitress Dolores Dante, but those two were the only parts of the PBS show I found.) That’s Eileen Brennan as Clements.

Millwork ain’t easy, millwork ain’t hard

Millwork it ain’t nothing but an awful boring job

I’m waiting for a daydream to take me through the morning

And put me in my coffee break where I can have a sandwich and rememberThen it’s me and my machine for the rest of the morning

For the rest of the afternoon and the rest of my life

I think I may actually prefer this version, just a little bit, over Taylor’s lovely standalone version on his 1979 album Flag, which I encountered before seeing the PBS musical. Interpolating bits of Clements’s interview gives it an extra kick.

And goddamn, that interview! It’s among the more harrowing jobs discussed in Working; hot, painful, repetitive work, the same series of movements every 40 seconds, up to 800 times a day for the lighter pieces, or 400 for the heavier large suitcases.

The tank I work is six foot deep, eight foot square, and then in 40 seconds, you take the wet felt out of the felter, put the blanket on and rubber sheeting, draw out the excess moisture, wait two, three seconds, take the blanket off, pick the wet felt up, balance it on your shoulder, know where you’re holding without tearing it all to pieces, it’s wet and will collapse, reach over, get the hose, spray the inside of the copper screen to keep from plugging, turn around, walk to the hot, dry die behind you, take the hot piece off with your opposite hand, set it on the floor, this wet thing is still balanced on my shoulder.

Put the wet piece on the dry die, push this button, let the dry press down, inspect the piece we just took off, the hot piece, stack it, count it, you get a stack of 10, push it over, start another stack. Then go back, put our blanket on the wet piece, coming up in the tank and start all over. Forty seconds.

It’s a holiday, so I feel free to digress: The above is a lightly condensed version of Clements’s description, from a 1979 episode of Terkel’s radio interview show from WFMT in Chicago.

The archives are AMAZING and searchable, and WFMT still plays a “Best Of Studs Terkel” episode every Friday at 11 p.m. This week, as WFMT does every year, they’re replaying Terkel’s 1963 story interviewing people on a train making its way to DC for the March on Washington for Jobs And Freedom. Give that a listen and imagine what it must have been like, traveling to the march long before it turned into American History.

OK, digression over, and back to Working, that search for meaning in our work, and our hope that somehow it matters, eventually, perhaps even for our children. Over the years, I’ve sometimes thought of something said by steelworker Mike LeFevre, whose interview leads off the book. Right after saying he doesn’t get excited by his job in a steel factory, he reflects on how everyone knows about the pyramids, but not about the people who built them or the lives they led.

Pyramids, Empire State Building—these things just don’t happen. There’s hard work behind it. I would like to see a building, say, the Empire State, I would like to see on one side of it a foot-wide strip from top to bottom with the name of every bricklayer, the name of every electrician, with all the names. So when a guy walked by, he could take his son and say, “See, that’s me over there on the forty-fifth floor. I put the steel beam in.” Picasso can point to a painting. What can I point to? A writer can point to a book. Everybody should have something to point to.

Another digression, if you don’t mind, since I’m free associating anyway. Enjoy for five minutes this 2016 Time video essay on that iconic 1932 photo of ironworkers having lunch in the sky while building 30 Rockefeller Center:

But nobody thought to take all their names and put them on the building.

Terkel’s interviews brilliantly capture that sense of wanting to be acknowledged, not only with a paycheck or a tip, though those are absolutely necessary, but with some kind of recognition as a human: We want to know that what we do all day matters somehow, that we’re humans with connections to other humans, that we won’t just vanish — even as we know that we’re all fated to eventual invisibility. (It is of some comfort, perhaps, that some day even Donald Trump will be nothing but a footnote.)

Terkel addresses that, too, in his introduction, writing

In all instances, there is felt more than a slight ache. In all instances, there dangles the impertinent question: Ought not there be an increment, earned though not yet received, from one’s daily work—an acknowledgement of man’s being?

That question, never fully answerable, makes Working, somewhat paradoxically, timeless, even if the people in it, and even their jobs, are long gone. Surprisingly few of those jobs have disappeared entirely, other than perhaps switchboard operators, although many of the indignities inherent to them are still very much with us, like the supervisor listening in on calls, waiting to pounce on any variance from the performance standards. It may be an AI program, but Big Brother is still always watching.

Throughout the book, there’s a healthy distrust, for the most part, of the alleged “work ethic,” as much in question in the early 1970s as now, though politicians endlessly invoke it as just a natural, wonderful thing. Richard Nixon then, Trump and Republicans now, with their false insistence that throwing millions of people off Medicaid will only affect the lazy, undeserving layabouts. The only difference, I suppose, is that Donald Trump, the laziest, most incompetent president we’ve ever had, simply makes the naked hypocrisy of that old lie far more visible.

Terkel noted in his 1974 introduction, as if it were a new development, that

Lately there has been a questioning of this “work ethic,” especially by the young. Strangely enough, it has touched off profound grievances in others, hitherto devout, silent, and anonymous. Unexpected precincts are being heard from in a show of discontent. Communiques from the assembly line are frequent and alarming: absenteeism. On the evening bus, the tense, pinched faces of young file clerks and elderly secretaries tell us more than we care to know. On the expressways, middle management men pose without grace behind their wheels as they flee city and job.

It’s perhaps clearer, 53 years later, that this is more of a steady state, although it also feels like the questioning is new every time it appears — as when pundits were surprised, in the wake of the pandemic, that many Americans weren’t so crazy about going back to low-paid work. Especially when, for a time, the shakeup in the labor market led to a lot of chances to find higher salaries, and how dare people not be satisfied with a national minimum wage that hasn’t increased since 2009. God, remember this whiny placard in an El Paso restaurant from June 2021, complaining that emergency unemployment benefits had turned everyone against work?

![Photo of a placard on a table in a restaurant: 'Sadly, due to government handouts, no one wants to work anymore. [in boldface:] Therefore, we are short staffed. [Regular text resumes:] Please be patient with the staff that did choose to come to work today and remember to tip your server. They chose to show up to serve you.' Photo of a placard on a table in a restaurant: 'Sadly, due to government handouts, no one wants to work anymore. [in boldface:] Therefore, we are short staffed. [Regular text resumes:] Please be patient with the staff that did choose to come to work today and remember to tip your server. They chose to show up to serve you.'](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!95Tn!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fcbde0069-6341-4b92-81ae-19b2bfb96fca_510x680.jpeg)

Starve People Like ‘Dogs’ To Make Them Take Crappy Jobs, Laura Ingraham, Bar Rescue Guy Agree

$600 Emergency Unemployment Reduced Job Searches — When There Were No Jobs

And now, the Rest of the Story: The restaurant’s owner took out over a million dollars in PPP loans to stay afloat and keep workers employed. But according to Fight for 15, server jobs at the steak house paid just $2.13 an hour, plus tips. Benefits? An employee discount on meals and some kind of “referral program” for bringing in new dupes workers.

This is where, if I had any work ethic, I’d close with a brilliant observation about how all this could be overcome with a universal basic income, or by a revolution in how we relate to our work. But damn, did you see the word count on this piece? I’ve done enough, it’s quitting time.

Oh, and also check out this cool WBEZ Chicago “Radio Diaries” special on the rediscovered tapes of Terkel’s interviews, which is fascinating but can’t be embedded. NPR also collected several short pieces from those tapes, if you want smaller doses. Enjoy your Labor Day, comrades!

[WFMT / Studs Terkel Radio Archive at WFMT / WBEZ / NPR: ‘Working’ Then and Now]

Yr Wonkette is funded entirely by reader donations. If you can, please become a paid subscriber, or encourage us to keep our lazy asses bringing you the news and snark with a one-time donation!

www.wonkette.com (Article Sourced Website)

#Fine #Heres #Labor #Day #Studs #Terkel