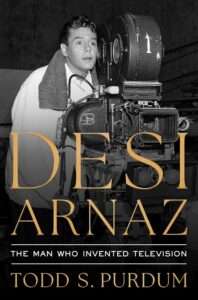

Desi Arnaz: The Man Who Invented Television, by Todd S. Purdum, Simon & Schuster, 368 pages, $29.99

There’s been plenty written about I Love Lucy, but mostly about Lucy. What about I?

Desi Arnaz—the man who played Lucille Ball’s husband on the show, and was married to her in real life too—was not just spectacularly successful; he was a revolutionary who changed TV in ways we feel to this day. But his fame has faded: I Love Lucy reruns used to be omnipresent, but if you see one now, it’s likely to be on a channel with lots of ads for catheters.

Todd S. Purdum’s biography—Desi Arnaz: The Man Who Invented Television—gives us a chance to revive the man’s memory.

Desiderio Alberto Arnaz y de Acha III was born in 1917 in Santiago de Cuba. His father was the mayor, his family had an illustrious history, and he was raised in luxury. But when a mob burned down his house during the Cuban Revolution of 1933, it was time to leave. By 1934, he was living in Miami at a time when it had very few Cubans.

Arnaz had talent as a singer and musician, and the nationally known bandleader Xavier Cugat hired him. The good-looking and charismatic Arnaz soon scored great success on his own, particularly when he popularized the conga. He was featured in the 1939 Broadway musical Too Many Girls, then went to Hollywood to repeat his role in the film version for RKO.

The star of the movie was Lucille Ball, six years older, who had already appeared in over 50 films. Lucy and Desi were married before the year was over.

The 1940s were a tough decade for the couple. Professionally, Arnaz’s Hollywood career didn’t take off—Ricardo Montalbán became the screen’s leading Latin lover—and he was soon back to being a bandleader (and picked up his signature tune “Babalu”). Ball, approaching 40, kept appearing in movies but couldn’t quite break onto the A-list.

And privately, the couple often fought. One constant source of tension was Arnaz’s roving eye. He regularly visited prostitutes.

In the late ’40s, Ball was starring on the radio sitcom My Favorite Husband. She was asked to do a TV version. At this time, television was held in low regard. Going from movies to TV would be a big step down, all but admitting your film career is over. On the other hand, a hit in a new medium could bring new life to her career.

Ball agreed to do it on one condition: Her co-star would be Arnaz.

I Love Lucy, debuting in 1951, went on to become an enormous television hit—the biggest of the decade, maybe ever. But there were huge obstacles to overcome. Even before the show was scheduled, there was pushback from CBS and potential sponsors: Would people invite into their living rooms an all-American beauty married to a Cuban with an accent?

This has long been a problem in the entertainment business. People in the uncertain world of showbiz generally attempt to give the customers more of the same. But trying to be inoffensive underestimates the audience. Investing in something different carries risk, but the forward leaps that change the medium come from taking a chance.

To cut down on the chance, Lucy and Desi—and their newly formed Desilu Productions, run by Desi—created a live vaudeville act where Desi was the bandleader and Lucy would interrupt. It went over well, and it became the basic concept of I Love Lucy, where Lucy was always begging her husband to put her in the act.

Getting the OK for Arnaz’s casting was just the beginning. For one thing, the couple did not want to leave Los Angeles. But back then there was no coast-to-coast transmission; TV was shot in New York and broadcast to the eastern half of the United States. A film camera (videotape didn’t exist yet) would record a monitor and create a kinescope—an awful-looking reproduction that would be broadcast in the western states.

Arnaz would not accept kinescopes. He wanted his show to have a high-quality film look. On top of that, he wanted the show recorded live with three cameras and in front of an audience. This presented almost insurmountable technical problems, but he wouldn’t take no for an answer.

So Arnaz contacted an old acquaintance, the Oscar-winning cinematographer Karl Freund, who initially said it couldn’t be done. The reason movies are shot with one camera is that each angle needs its own lighting. Freund ultimately came up with lighting from above, so several cameras could shoot the scene from wherever they wanted. (While every innovation on the show went through Arnaz, they didn’t all come from him.)

But how would an audience see the action with all the technical stuff in the way? I Love Lucy set up bleachers where the audience was seated above the cameras and had a clear view of the actors.

It sounds obvious today, but it was revolutionary then. Not that every show adapted immediately. In the 1960s, most popular sitcoms tended to be shot like a film, with one camera and no audience. That’s how it worked with The Andy Griffith Show, The Beverly Hillbillies, and Bewitched. But by the ’70s, the tide turned in Arnaz’s favor: For the rest of the century, a majority of the most popular sitcoms were recorded live with multiple cameras—All in the Family, Happy Days (during its highest-rated years), Laverne & Shirley, The Cosby Show, Cheers, Roseanne, Seinfeld, Friends.

Then an odd thing happened in the 21st century: TV aficionados started treating one-camera shows (Arrested Development, The Office, 30 Rock, Modern Family) as if they were innately superior. The argument was that the approach offered more subtle performances, more intricate dialogue, more complex editing and cinematography. But as Lucy and Desi knew, there’s a certain life to comedy when the actors are playing to an audience and off an audience. To say one format is simply better is like saying movies are naturally superior to stage plays.

It’s been 20 years since a live sitcom won the Emmy for best comedy (Everybody Loves Raymond). And yet the most popular sitcom by far over the last 20 years—The Big Bang Theory—was recorded live. A little touch of Lucy has survived.

Another innovation of Arnaz’s: Desilu owned the episodes after they were broadcast. In an age before people knew the commercial potential of reruns, no one figured the episodes would have much value. Not that Arnaz had such amazing foresight—he just figured he might be able to sell them to foreign nations. Today, it’s understood that repeated showings of a hit are where the real money is made.

This being the 1950s, there was also some political trouble when Lucy was accused of being a Communist. Arnaz swung into action. He called the president of CBS and the head of Philip Morris, the tobacco company that sponsored I Love Lucy. He called Rep. Donald Jackson (R–Calif.), who sat on the House Un-American Activities Committee. And he called an old acquaintance: FBI head J. Edgar Hoover. He was able to nip the rumor in the bud.

With I Love Lucy in the No. 1 spot (one season it got a 67.3 rating—unimaginable in today’s crowded marketplace, where shows celebrate when they get a 10), Desilu started branching out, producing such hits as Our Miss Brooks and December Bride. Arnaz started buying more and more space—the crowning touch being the purchase of the old RKO lot where Desi and Lucy met. At that point, the Desilu empire had more space than the major studios.

But Lucy and Desi’s marriage was crumbling. They divorced in 1960, and Arnaz sold his interest in Desilu in 1962. The last hit show he was involved in was The Untouchables (1959–1963). Lucy kept doing sitcoms: She stayed in the top 10 into the 1960s and ’70s with The Lucy Show and Here’s Lucy. Eventually, though, even Lucy got old, and old-fashioned.

Arnaz continued in TV, mostly as a producer, but it was never the same. He lost his zeal and gained a drinking problem. Add a longtime smoking habit, and he developed serious health problems, dying in 1986 at age 69.

Lucille Ball is still part of the national consciousness. People fondly remember her stomping grapes, or dealing with chocolates on a conveyor belt, or getting drunk as she does an ad for Vitameatavegamin. Yet each year the memory grows dimmer. And her husband, if he’s remembered at all, is mostly seen as her straight man, putting up with her wacky schemes, telling her she has some ‘splainin’ to do, occasionally blowing his stack and shouting at her in excited Spanish.

But as Purdum demonstrates, Arnaz was much more than that. If tonight you watch a rerun of Friends or The Big Bang Theory, know that you owe a small portion of your laughter to Desi Arnaz.

reason.com (Article Sourced Website)

#Desi #Arnazs #revolution #televised