WARNING: This story details allegations of child abuse.

In the days leading up to his death, a 12-year-old boy in the care of two Burlington, Ont., women was experiencing “severe malnutrition” and weighed less than he did at age 6.

That’s according to Dr. Emma Cory, a pediatrician called by the Crown on Monday as an expert witness at the trial of Brandy Cooney and Becky Hamber, who’ve pleaded not guilty to first-degree murder in the proceedings that began last month.

The two were in the process of adopting the boy, known as L.L., and his young brother, referred to in court as J.L. The identitites of both Indigenous boys are protected under a publication ban.

Cooney and Hamber are also charged with confinement, assault with a weapon — namely zip ties — and failing to provide the necessaries of life to J.L.

The judge-only trial, under Justice Clayton Conlan, is underway in Superior Court in Milton and is expected to continue into November.

The Crown argues Cooney and Hamber despised the boys and locked them in their rooms, with L.L. being confined for most of the last year of his life. The Crown also argues the couple surveilled the boys on cameras, restricted their food and forced them to exercise.

In cross-examinations of witnesses, the defence has focused on the lack of support provided to the prospective adoptive parents by the Children’s Aid Society (CAS) and L.L.’s reported challenges, including aggression. The lawyers for both women have also questioned whether he had an eating disorder or other food-related syndrome.

Cory is with the Hospital for Sick Children in Toronto and provides medical care for suspected victims of abuse and neglect. She analyzed L.L.’s health records before and after he died on Dec. 21, 2022.

Throughout Cory’s testimony, which began Monday and continued into Tuesday, Cooney and Hamber sat hunched over in separate prisoner’s docks, and appeared to be taking notes by hand, rarely looking up. Both had their hair pulled back and wore green jail-issued jumpsuits and blue medical face masks.

The two accused are being represented by their own defence.

Boy looked like a ‘Holocaust survivor,’ says defence

Cory did not assess or treat L.L. while he was alive, but reviewed years worth of medical records, including from family doctor visits, and charted his growth.

She said she had no concerns with his weight or height before he lived with Hamber and Cooney in 2017.

He’d been a healthy child living with a long-term foster family in Ottawa, where he and his younger brother were born, Cory said. His foster mom previously testified he’d had a huge appetite and wasn’t a picky eater.

Records from a doctor’s appointment in 2021 show L.L. had lost a significant amount of weight.

Hamber’s lawyer, Monte MacGregor, played the court a video of L.L. from October 2022, months before his death.

He said the boy, with caved-in cheeks, resembled a “Holocaust survivor.”

When L.L. saw the same doctor, on Dec. 13, 2022 — eight days before his death — he weighed just 48 pounds and was about four-foot-five, Cory said. He would have been smaller than more than 99.99 per cent of children his age, and had stopped growing.

His family doctor recorded the boy had “lost weight and was clearly quite thin,” and had sent a referral for him to be assessed for an eating disorder, she said.

That doctor has not yet been called to testify, and Cory said that from his notes, she does not know everything that he discussed with other medical professionals, or Cooney and Hamber.

The judge interjected to say that while L.L’s family doctor “is not on trial here,” he finds it “shocking” that his patient could experience a dramatic weight loss without “records about specific things done.”

Both women’s lawyers asked Cory if she would have expected the family doctor to send L.L. to a hospital following the 2021 or 2022 appointment.

Cory stressed that although she “would have been concerned” and agreed that L.L.’s weight should’ve been “a clear indication this is a problem,” she did not have enough information to say for sure.

The pediatrician said she also didn’t have enough evidence to diagnose L.L. with an eating disorder and he didn’t have any chronic illnesses.

While the cause of L.L.’s death has not been established in court, Cory said, “For children with severe malnutrition, the worst potential outcome is death.”

Women questioned if boy was dying: Crown

Cory said there would’ve been obvious signs that L.L. was malnourished while in Cooney’s and Hamber’s care. He could’ve experienced low energy, sagging skin, more bruising, trouble focusing and bleeding gums.

In November, the Crown alleges, the two women were aware L.L. wasn’t well. In deleted text messages later recovered by police, they discussed how L.L. was shivering, locked in his basement bedroom, and struggling to focus, speak or stand, said Crown attorney Kelli Frew in her opening statement. He had a nose bleed and was vomiting.

They describe him in their texts as “drunk” and question if he’s dying, Frew said.

“They do not call for help, take him to a hospital or reach out to anyone.”

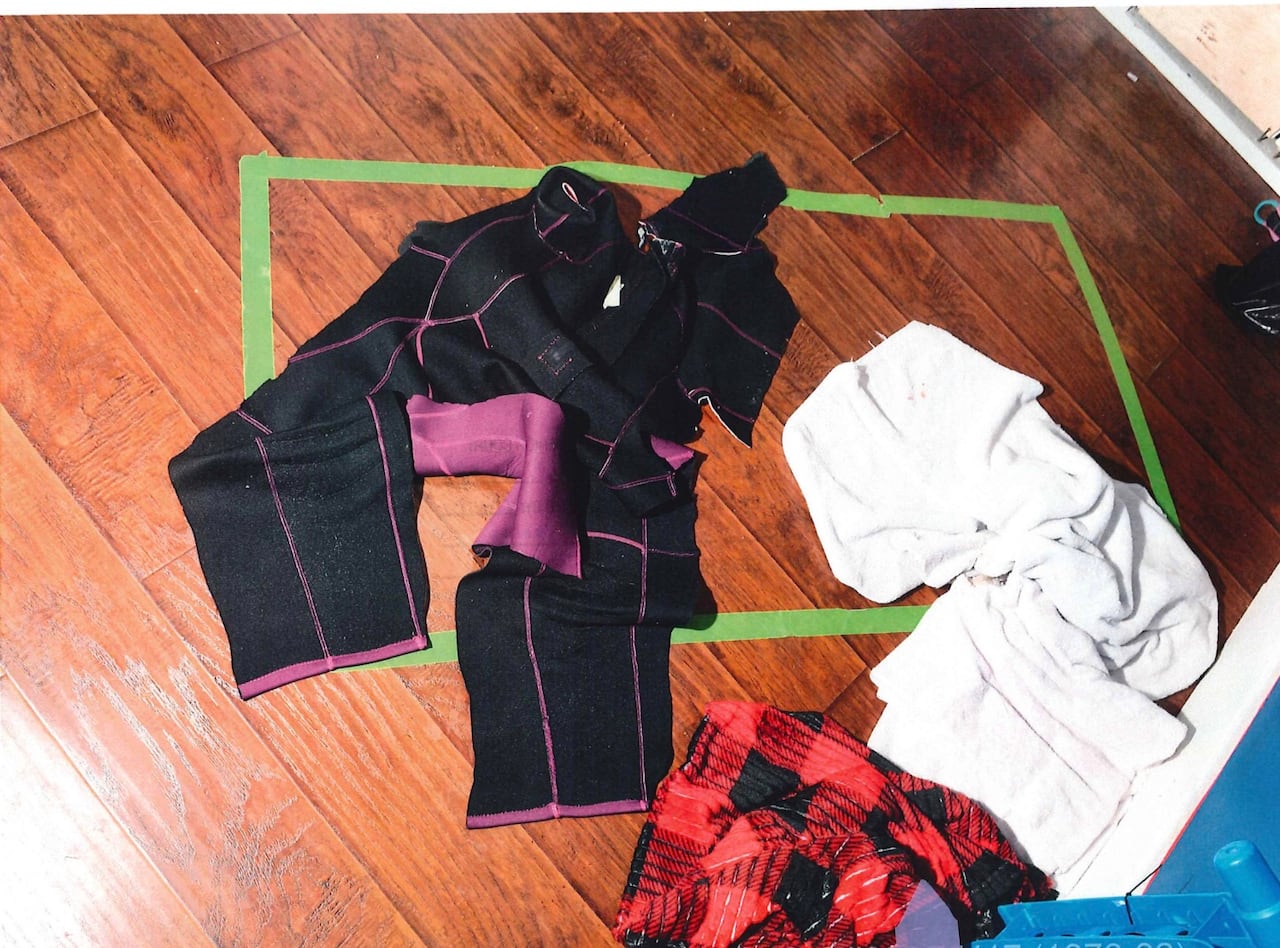

Instead, they temporarily put a space heater outside his room, turned the heat up in the home, swapped out his wetsuit for clothes, socks and a toque, and gave him blankets and a walkie-talkie to call for help, Frew said.

They took him to the family doctor for the annual checkup weeks after that.

On the night of Dec. 21, L.L. “lay dying on the floor of that same room, dressed back in the wetsuit, soaking wet, physically looking more and more like that of an average six-year-old,” Frew said.

First responders found him there, according to an agreed statement of facts, with the wetsuit cut off his body and tossed near a mesh cot — the only piece of furniture in his room.

A police officer went to the kitchen and saw all the cupboard doors had child locks on them, according to the statement. He saw a smoothie bottle with a straw in the sink — Hamber said the smoothie was L.L.’s dinner — and an empty bottle that contained milk.

L.L., whose core body temperature was extremely low and hypothermic, died in hospital soon after.

If you’re affected by this report, you can look for mental health support through resources in your province or territory .

www.cbc.ca (Article Sourced Website)

#Boy #died #care #Burlington #Ont #women #severe #malnutrition #expert #tells #murder #trial #CBC #News