The provincial government that routinely demands Ottawa stay in its jurisdictional lane is keen to swerve into another jurisdiction’s lanes.

Bicycle lanes.

Transportation Minister Devin Dreeshen has signalled he wants cities, particularly Edmonton and Calgary, to alter or remove any cycling lanes that impede automobile traffic — and avoid future bike lanes that do so. If they don’t, Alberta might create the powers to do so itself.

Alberta wouldn’t be the first province to insert itself into the bike lane debate, following fellow conservative politicians in Ontario and, more recently, Nova Scotia. Whether it’s dubbed ending the “war on cars” or fighting for “common sense,” the fight over which road users get asphalt space has sounded similar across the country.

But there are lessons in a new court ruling that struck down the largest province’s bid to tear out bike lanes in Toronto, beyond the constitutional violations cited by the judge.

Ontario launched its plan to dismantle Toronto bike-lane barriers by stating, repeatedly, that they worsen vehicle congestion by compromising vehicle space. It’s the same logic Dreeshen applied last month, ahead of his meeting on the topic with Calgary Mayor Jyoti Gondek: “While we fund major infrastructure projects, like the Deerfoot [Trail], to improve traffic flow and reduce congestion, some local decisions are moving in the opposite direction, removing driving lanes.”

Cycle Toronto’s court challenge of Ontario’s “Reducing Gridlock, Saving You Time Act” got the courts to peel back the advice and research that underpinned Ontario’s claims against bike lanes. Or, mainly, the lack thereof.

“To the contrary, records produced by the government in this litigation show that the internal advice prior to passing Bill 212 was that protected bike lanes can have a positive impact on congestion and that removing them would do little, if anything, to alleviate gridlock, and may worsen congestion,” Ontario Justice Paul Schabas’ ruling states.

An Ontario court ruled against the Ford government’s plan to remove bike lanes along three major Toronto streets. CBC’s Tyler Cheese has reaction from those on both sides of the debate.

The decision refers to an engineering firm the province hired to study its car lane restoration. It reported: “While removing the bike lanes and replacing them with traffic lanes may increase the vehicle capacity along the immediate length of the roadway, the actual alleviation of congestion may be negligible or short-lived due to other confounding factors or induced demand.”

Induced demand refers to a well-travelled concept in transportation engineering that expanding road capacity will attract more automobiles, and therefore restore any congestion that briefly gets eliminated.

(Meanwhile, Schabas also found that the health and safety risks to cyclists if they lost their barrier-protected routes through key parts of downtown Toronto was easily proven.)

Would the rise and ebb in vehicle traffic behave any differently if the protective curbs for safer biking were removed in favour of an extra driving lane on 12th Avenue S. or Fifth Street S.W. in Calgary?

Dreeshen emerged from his July 30 meeting with Calgary Mayor Jyoti Gondek pleased that she agreed with his interest in removing problematic bike lanes.

“These bike lanes are not fixed,” she told reporters after the sit-down. “If a bike lane is causing any concerns with congestion or parking, our traffic team is open to reviewing and making any necessary changes.”

The question, then, could come down to whether Calgary and Alberta could find a problem that Toronto and Ontario did not.

In 2015, the city added its downtown network of temporary barrier-protected bike lanes on a few streets, as a pilot project.

City officials measured the change in motorist travel times next to the bike-safety bollards. Along an eight-block stretch of Eighth Avenue S.W., there was no change in westbound traffic during the afternoon peak, and a 15-second decrease going the opposite way in the morning, according to a 2016 city report.

What impact did the cycle lanes on Fifth Street have, for their 14 blocks? In the afternoon rush, commutes were up by 10 seconds.

Morning travel times rose by 90 seconds along the downtown-spanning stretch of 12th Avenue S., including an added 13 seconds of delay at the intersection of two new bike lanes — but officials in that report pledged to review signal timing and road design before the lane would become permanent.

Would these numbers justify the removal of bicycle lanes, having not persuaded council to do so back then? And what trade-offs are acceptable for creating a safe route for cyclists around the city’s centre?

The city also measures the number of cyclists (and other users) getting into and going through Calgary’s business core. In that respect, the statistics show little before-and-after change, despite promoters’ high hopes for a big boost to cyclist numbers.

In 2014, before the protected bike lanes, the share of downtown commuters who came in or out on two wheels was 1.7 per cent. Rates rose before the pandemic to 2.7 per cent in 2017 — that still looks puny in relative numbers, but that’s more than a 50 per cent jump in bike commutes.

However, it dipped to 1.9 per cent in the 2024 transportation count.

Dreeshen remarked on that figure after his meeting with Gondek. “So that means 98 per cent of people are commuting on a daily basis in their vehicles,” he told CBC Radio’s The Homestretch.

“And obviously when you take away a driving lane for vehicles to put in a bike lane you’re helping that small two per cent of commuters at the expense of drivers.”

Dreeshen is incorrect that it’s two versus 98 per cent, as the non-cycling total also includes transit users and people walking into downtown; automobile drivers and passengers account for 59 per cent of downtown visits, according to city statistics.

And there’s another statistic that Gondek highlighted after seeing the minister: less than one per cent of Calgary’s road surface is dedicated to bicycles.

This certainly stands to become political fodder, coming into the fall’s municipal votes. A conservative-aligned Edmonton mayoral candidate is echoing provincial rhetoric with a promise to halt any new bicycle lanes, and Calgary Coun. Dan McLean has said he wants the Eighth Avenue route axed and others reviewed.

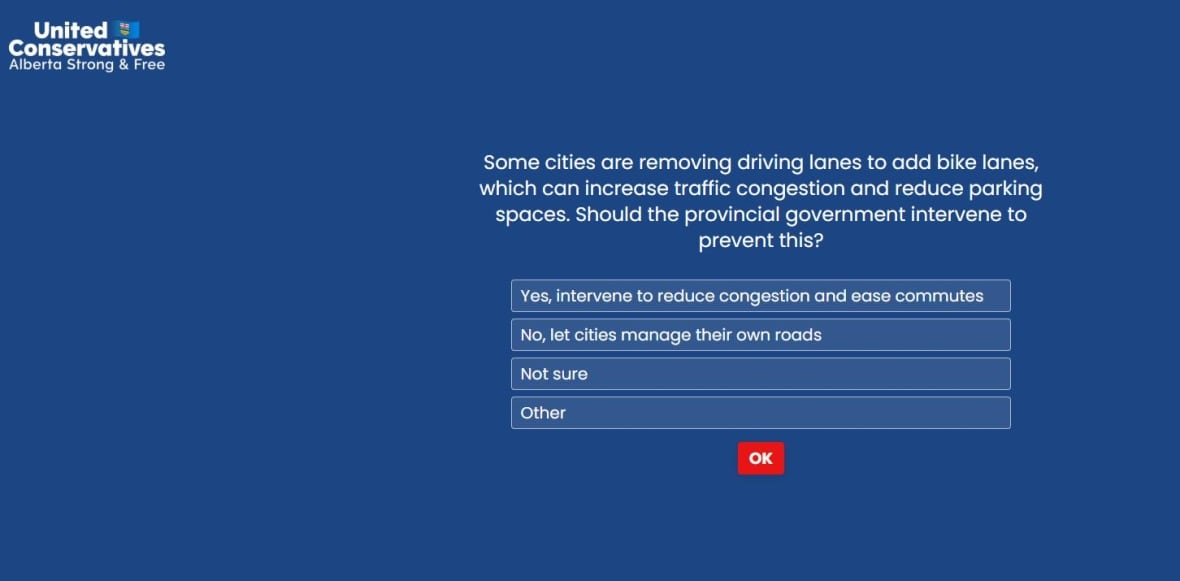

Meanwhile, the UCP issued a letter to members this week in Dreeshen’s name, urging them to weigh in on a party survey’s question about a potential bike lane crackdown — along with other questions inviting supporters to endorse existing UCP policies on taxes, school library content and private surgery clinics.

“Of course, not everyone lives downtown. But many of us travel into the city for work, errands, or events, and we feel the impact too,” Dreeshen’s party email stated.

This rhetoric gets at the heart of why provincial conservatives like to make hay about curbs and lane paint in a city’s core, where voters tend to skew NDP or Liberal. Their own suburban and small-town base would likely be bothered by road space they can’t drive on or park in, especially on a busy game night or lunch hour when they venture downtown.

Just as planning the route for the Green Line LRT is supposed to be the city’s jurisdiction, so is the addition and subtraction of bicycle lanes — though at least with the LRT, the Smith government can argue they’re a funding partner.

The Smith government’s keen interest in downtown bicycle barriers comes alongside Municipal Affairs Minister Dan Williams’ comments this week to Postmedia, about cities’ business being provincial business.

“Every single municipality in this province from the biggest cities to the smallest summer villages are creatures of legislation enacted by this legislature and this government has authority over those municipalities,” he said.

Technically, this is true, as it is in Ontario and elsewhere. It’s not common, however, for provincial ministers or the premier to state this fact, given all its implications for interventions into the decisions of elected city or town councils.

“I’d like to see the premier stay in his lane — and it’s not a bike lane,” a Halifax city councillor said about Nova Scotia Premier Tim Houston’s threats to crack down on a cycling infrastructure proposal he has opposed.

But what happens if a provincial government sees any urban lane as its lane?

www.cbc.ca (Article Sourced Website)

#ANALYSIS #Alberta #minister #threatens #axe #bike #lanes #case #CBC #News