“If someone can do something, by all means, go for it. I can’t do anything. Don’t curse me,” Masoud Pezeshkian, Iran’s President, told a gathering of university students and academics in early December. At another meeting with provincial Ostandars (governors) and local officials, the President said, “solve your problems yourselves. You shouldn’t think that the President can make miracles happen.” Mr. Pezheshkian, a heart surgeon-turned politician who won the 2024 elections on a platform of reform, said his government was “stuck, really badly stuck”, referring to Iran’s structural problems.

The economy, already reeling under Western sanctions, came under added strain after the June 2025 war with Israel and the U.S. Already grappling with hyperinflation and a tanking currency, a drought last year compounded Iran’s economic distress, while periodic water and power cuts deepened public frustration. The government appeared largely helpless, while the security establishment prepared for the next round of confrontation with Israel. “Iran was a tinderbox,” a Tehran-based academic said. “All it wanted was a spark.”

The fuse was lit on December 28, when traders and shopkeepers in Tehran’s Grand Bazaar went on strike over the collapsing currency, the rial. The bazaar carries immense symbolic weight in Iran’s revolutionary folklore. In the late 1970s, it was a key hub of revolutionary activity. The bazaaris (the trading class), conservative in outlook and angered by the Shah’s economic policies, threw their weight behind the anti-Shah movement, which snowballed into a nationwide uprising that brought down the monarchy in 1979.

In December 2025, the bazaaris shut their shops and staged rallies, demanding solutions to mounting economic grievances. The authorities initially showed restraint and promised to address the shopkeepers’ demands, but protesters remained defiant. And then, on January 2, after meeting Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu in Florida, U.S. President Donald Trump warned Iran’s rulers against killing protesters. “The U.S. is locked and loaded,” he wrote in a social media post.

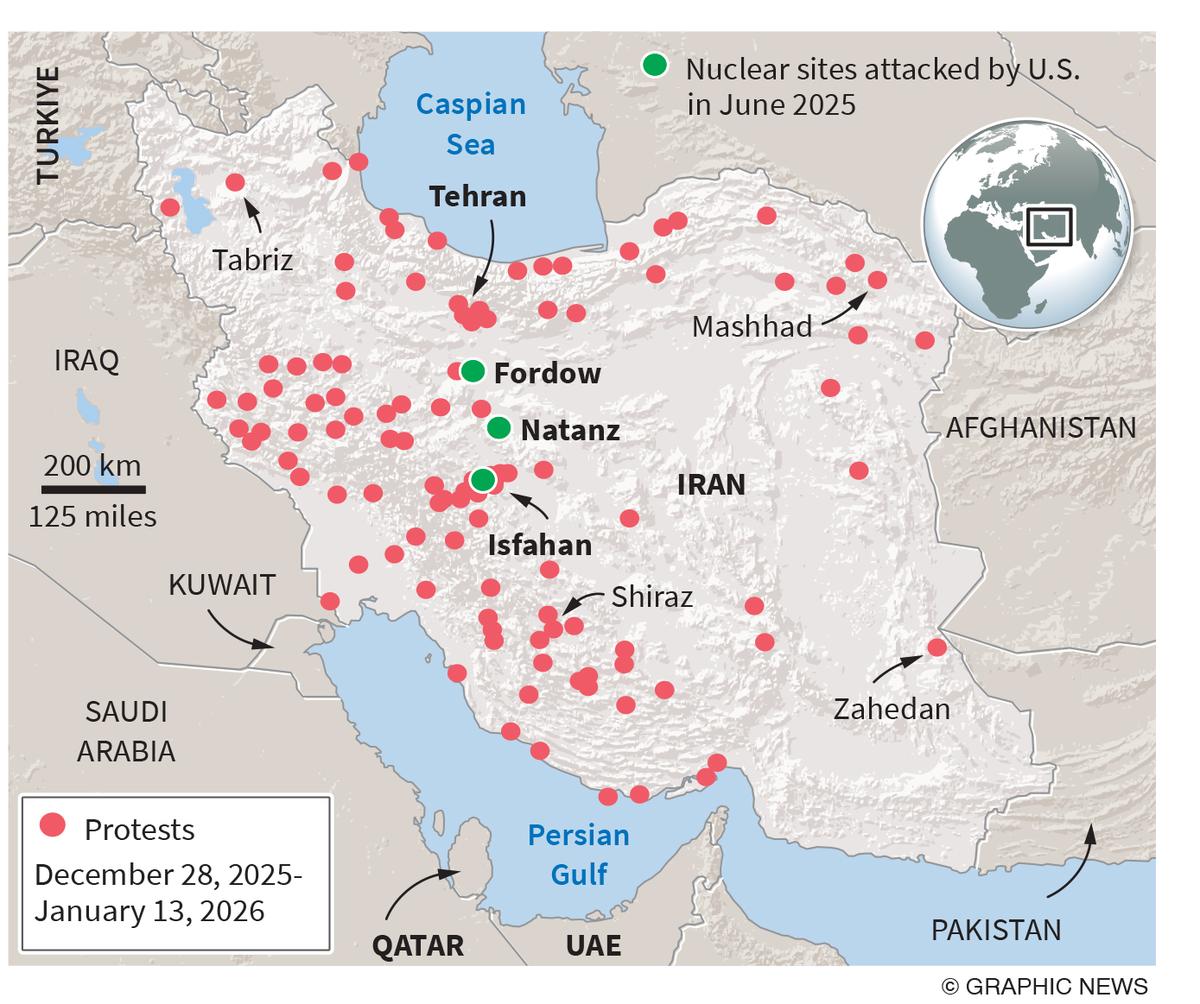

Days later, as protests spread across the country, Iran imposed a nationwide Internet shutdown. A brutal crackdown followed. On January 10, security personnel used lethal force to crush the unrest. According to two Iran-watching organisations based in the U.S. and Norway, at least 3,000 people were killed. State media reported that more than 130 security personnel were also killed in the violence. Reza Pahlavi, the U.S.-based son of the late deposed monarch, emerged in Western media as the voice of Iran’s opposition.

He urged the protesters to sustain the pressure and unveiled a transition plan from America — which kept reinstating the monarchy as one of the options. Mr. Trump, for his part, called on “Iranian patriots” to keep protesting and “take over institutions”, promising that “help is on the way”. But after the January 10 crackdown, the protests appeared to lose momentum, while government officials claimed that normalcy was returning. Mr. Trump, meanwhile, seemed to have developed cold feet about military action — at least for now. He said he was “notified” that Iran had halted the planned execution of hundreds of protesters, calling it “good news”.

Cycles of protests

The Islamic Republic, founded in 1979 after the ouster of the Shah, has witnessed several waves of protests ever since. In 1999, students launched a mass agitation demanding social and political reforms. The trigger was the shutdown of a reformist newspaper at the University of Tehran. As protests spread across campuses, security forces moved in with force to suppress them. In 2009, after allegations of a massive electoral fraud surfaced following the presidential election in which incumbent Mahmoud Ahmadinejad was declared winner, tens of thousands took to the streets. The unrest, which came to be known as the Green Movement, eventually lost momentum.

There were repeated protests over economic grievances in 2017 and 2019, but none seriously shook the state. In September 2022, after Mahsa Amini, a 22-year-old Kurdish woman, died while in police custody, nationwide protests rocked the country once again. But by far the 2025-26 agitation proved the gravest challenge the Islamic Republic has faced. This time, the protesters took to the streets, with some calling for the overthrow of the regime, while the U.S. threatened to bomb Iran. It was a rare and perilous moment of convergence of both internal instability and the threat of external aggression.

“It’s not that Iran doesn’t want to solve its economic problems. Nor does the state want to live in perpetual cycles of unrest. There are issues of corruption and cronyism. But what has really tied the hands of the regime are the sanctions,” said the Iranian academic.

Iran is among the most heavily sanctioned countries in the world. The U.S. imposed the first batch of sanctions on Iran’s economy immediately after the 1979 revolution — it banned oil imports from Iran and froze some $12 billion in Iranian assets. In 1995, President Bill Clinton barred American companies from making investments in Iran’s hydrocarbon sector. In 2006, the UN Security Council imposed additional sanctions over its nuclear programme. The European Union would follow suit. In 2019, the first Trump administration designated the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps, a paramilitary unit, as “a foreign terrorist organisation”. Currently, Iran’s assets held overseas are largely frozen, its ability to trade freely is severely constrained and foreign countries and companies are effectively barred from making investments. Under sustained American pressure, several countries scaled back oil purchases from Iran, including India.

Sanctions on oil sharply reduced Iran’s foreign exchange earnings and slowed down its economic growth. The loss of revenues led to massive deficits, which were financed by monetary expansion, triggering hyperinflation. Tehran had in the past sought to engage the West and ease the economic stranglehold without loosening its ideological grip. In 2015, Iran reached a multilateral nuclear deal, agreeing to scuttle its nuclear programme and open its facilities for international inspection, while retaining its nuclear technology. In return, the U.S., then led by Barack Obama, and other powers pledged to remove economic sanctions. The Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), as the nuclear deal was called, was seen by many as a new beginning for Tehran.

But Israel staunchly opposed the deal, and lobbied against it. In May 2018, during his first term, Mr. Trump tore up the agreement by pulling the U.S. out of it despite UN certification that Iran was fully compliant with the terms of the agreement. He reimposed sanctions on Iran, effectively killing the JCPOA. In response, Iran started enriching uranium to levels beyond the limits set by the deal. In September 2025, European nations reimposed snapback sanctions, saying Iran had violated the JCPOA.

Amid fears of conflict and uncertainty, economic pains mounted. In December, the rial’s value fell by 16% — the currency lost roughly 60% of its value since the June war. Food inflation reached an annual rate of 72%, nearly double the official target. The Pezeshkian government tried to implement some reforms by increasing taxes and removing food and fuel subsidies, moves that only inflamed the public anger. The middle class bazaaris took to the streets first. Others soon followed, transforming a localised strike into a nationwide anti-government political agitation with geopolitical ramifications.

External interference

“In June, Iran was subjected to an illegal military attack by the U.S. and Israel. Over the past two weeks, Iran experienced a terrorist attack. We had Mossad agents directing rioters to attack police stations, schools and mosques. This was domestic terrorism,” Foad Izadi, professor of world studies at Tehran University, told The Hindu. “It initially started as a peaceful protest by merchants, who were upset about currency fluctuations, but that was quickly hijacked by Israel and the U.S.. They want [Reza] Pahlavi to be back in Iran,” he said, adding that Mossad itself had acknowledged having agents operating inside the country.

On January 2, on the day Mr. Trump declared the U.S. was “locked and loaded”, Mossad, Israel’s external spy agency, wrote on social media in Farsi, encouraging Iranians to protest against the government. “Go out together into the streets. The time has come,” Mossad wrote. “We are with you. Not only from a distance and verbally. We are with you in the field.” In October 2025, Haaretz, Israel’s liberal daily, reported that Israel was indirectly funding Persian language online campaigns targeting the Iranian government, and projecting Reza Pahlavi as the next Shah. This online network pushed out deep fake videos and misinformation during the June war, according to the report. On January 3, Mike Pompeo, former U.S. Secretary of State and CIA chief, wrote on social media, “Happy New Year to every Iranian in the streets. Also to every Mossad agent walking beside them.” On January 13, Channel 14, a far-right Israeli channel, reported that “foreign actors are arming the protesters in Iran with live firearms”.

Mr. Izadi said the Western media ignored these facts in their coverage of the “riots” in Iran. “Protesters don’t shoot at police. The West wants to portray that peaceful protesters were killed by the police, but in reality, Mossad agents were shooting at ordinary citizens because they want to increase the number of deaths so that they could get Trump to attack Iran,” added Mr. Izadi. “Pahlavi is also asking for a military attack by Trump. This is strange because if you want to be the king of your country you wouldn’t be inviting a foreign government to attack your country.”

A UN staffer based in Tehran told The Hindu that the protests had turned violent in several pockets. “There were incidents of gunmen from among the crowd targeting security personnel.” said the official. But groups based in the U.S. and Norway, which are critical of the Iranian clerical regime, claimed security personnel unleashed brutal violence against protesters. The government is yet to release the official toll. But Iran’s Foreign Minister Abbas Araghchi said “hundreds” were killed. “The government was in talks with the protesters and the internet was shut down only after we confronted terrorist operations and realised orders were coming from outside the country,” Mr. Araghchi said in an interview. The UN staffer in Tehran said on January 13 that protests had subsided but “the air is very tense and fearful”. “Many here say this kind of repression has never been seen. But there is no sign of weakness from the government’s side. They are holding up,” said the official.

According to Arash Azizi, an Iranian author who is teaching at Yale University, the Islamic Republic “might have quashed this wave of street protests but, unlike 2022, it has not returned to stability”. “Its core policies and structures remain untenable. It can barely restore the social equilibrium.”

He said the regime has committed a grave crime by killing “thousands” of protesters. “The opposition remains fragmented and in shock of the massacre. It would need to get its act together if it is to reach its ambitions. Barring that, it is likely that forces inside the regime will implement changes to the regime’s core policies and structures as they seek a new deal with the people and also the U.S.,” Mr. Azizi, author of What Iranians Want, told The Hindu.

Curse of geopolitics

Iran has long been in Washington’s crosshairs. After the September 11, 2001 attacks, Iran was among the first countries to condemn al-Qaeda assault on the U.S., and even offered cooperation for America’s war in Afghanistan. Yet in January 2002, then- U.S. President George W. Bush grouped Iran with North Korea and Iraq as part of an “axis of evil”. A year later, the U.S. invaded Iraq.

North Korea, sensing the danger, abandoned nuclear diplomacy and accelerated efforts to build a nuclear bomb — which it tested in October 2006. Iran built a nuclear programme, but stopped short of weaponisation, with the country’s clerical leadership issuing a fatwa (edict) against manufacturing a bomb. Instead, Tehran invested heavily in building its so-called axis of resistance (forward defence), involving Hashad al Shabi in Iraq, Hezbollah in Lebanon and militant groups in Palestine (Yemen’s Houthis would join the network later).

When the U.S. got stuck in Iraq, Iran steadily expanded its regional influence through the axis which it thought would ensure its deterrence. When Arab Spring-inspired protests plunged Syria, an Iranian ally, into a civil war, Tehran, along with Russia and Hezbollah, stepped in. They turned around the civil war by 2018. But the first blow came in January 2020 when the U.S. assassinated Qassem Soleimani, the charismatic head of the Quds Force, the external arm of the Revolutionary Guards, in an air strike in Baghdad. Soleimani was one of the key architects and executioners of the forward defence strategy. Soleimani’s killing disrupted Iran’s complex power projection in a volatile region.

After the October 7, 2023 Hamas attack, Israel took the war straight to Iran. On the one side it destroyed Gaza, and on the other, it went after Hezbollah and the Syrian government. Hezbollah was severely weakened after a month-long Israeli military operation in November 2024. In December, the Syrian government of President Bashar al-Assad collapsed when a Turkiye-backed jihadist militia, headed by Abu Mohammed al-Jolani, a former al-Qaeda commander, marched towards Damascus. With Syria fallen, Hezbollah rolled back and Hamas pushed to the ruins of Gaza, Iran suddenly lay vulnerable to external threats. And in June 2025, Israel began bombing Iran’s nuclear facilities. The U.S. joined in.

Israel has never hidden its desire for regime change in Iran. During the June war, Prime Minister Netanyahu had said regime change could be one of the outcomes of the attack. On Day 1, Israel carried out a large-scale decapitation strike killing several military chiefs. Iranian officials later claimed even President Pezeshkian was targeted. The Iranian state recovered quickly and hit back with ballistic missiles, eventually forcing Israel to agree to a ceasefire. But only the direct confrontation came to a halt. The rivalry continued.

Israel, and several U.S. politicians, including Republican Lindsey Graham, openly support Reza Pahlavi as a potential successor to the Islamic Republic. From Israel’s perspective, Iran is the only revisionist power in the region. No Arab country challenges Israel’s military dominance. If the Islamic Republic falls and a pro-American, pro-Israel dynast is installed in Tehran, Israel, with support from Washington, could redraw the geopolitical landscape of West Asia. As the Islamic Republic’s rivals seek regime change and Tehran seems determined to fight back, the protesters, who demand freedoms and reforms, risk being reduced to pawns in the broader games countries are playing.

Even though many, including German chancellor Friedrich Merz, predicted an imminent collapse of the Iranian government, that did not occur. Even at the peak of the protests, state institutions remained unified, with no visible cracks in the loyalty of the security apparatus. Earlier this week, tens of thousands took to the streets in support of the government.

The protesters, divided among separatists, liberals and monarchists, appeared to lack the political capital to bring down the republic. Questions also remain about what would follow the clerical leadership. Reza Pahlavi, who hasn’t set foot in Iran for over 40 years, lacks the organisational backing or popular appeal to emerge as a credible alternative in a country of over 90 million people. “He has been living off the money his father had stolen from Iran for the last 47 years. Now, he wants to become the king. His father came to power through an American-British coup, and the son wants to come to power through an American-Israeli colour revolution, which failed,” said Mr. Izadi.

But the ground reality appears more complex. “Back-to-back crises are fraying the social contract. Iranians demand structural reforms — if not regime change. The state understands this, but is unable to deliver. The push has to come from within. What you are watching on TV, the coronation of another Pahlavi, holds little significance for ordinary Iranians,” said the Tehran academic. “The revolution will not be televised”, he said, referring to the Gil-Scott Heron poem.

The republic may have weathered the storm for now, but tornadoes lie ahead. The economy remains in deep peril, trapped in cycles of crisis. Iran’s powerful external adversaries have read recurring protests as signs of state weakness. They are likely to intensify efforts to further isolate the country, tighten the screws of sanctions, and sow internal instability. Caught between a sanctions-battered economy, a state unable to reform, and open up and external rivals bent on forcing a violent regime change, the revolutionary road remains torn. As President Pezeshkian warned in December, nobody “can make miracles” to fix the country’s myriad problems.

www.thehindu.com (Article Sourced Website)

#Iran #protests #revolution #televised