We may earn money or products from the companies mentioned in this post. This means if you click on the link and purchase the item, I will receive a small commission at no extra cost to you … you’re just helping re-supply our family’s travel fund.

Some hotels become famous for views, chandeliers, and the names signed in their registers. Others are remembered for a darker reason: a single night when fire, collapse, or violence turned a place of rest into a scene of loss. In many cases, the aftermath changed building codes, emergency training, and the small design choices that decide who gets out in time. These properties have been rebuilt, renamed, or repurposed, but the stories still cling to their addresses, reminding cities that comfort means little without safety.

Winecoff Hotel, Atlanta

Before dawn on Dec. 7, 1946, fire climbed through Atlanta’s 15-story Winecoff at 176 Peachtree Street, and 119 people died. With a single main stair serving the upper floors, smoke rose fast, ladders topped out below the highest windows, and rescues turned into ropes, nets, and split-second judgment at the sill. Marketed as fireproof, the hotel had no sprinklers, no fire escapes, and weak warning systems, and the loss, which included teenagers in town for a youth conference, helped harden U.S. expectations for posted exits, redundant stairs, and protections that work while guests are asleep now.

Hyatt Regency, Kansas City

On July 17, 1981, the Hyatt Regency’s soaring atrium held a crowd for an evening tea dance when two suspended walkways failed and crashed into the lobby below. The collapse killed 114 people and injured 216, and rescuers worked deep into the night, lifting slabs with jacks, crawling under twisted beams, and triaging victims on whatever flat surface could hold a body. With more than 1,000 people in the space, the disaster became a watershed in engineering accountability, spawning investigations, lawsuits, and reforms, and proving how a small change in connections can carry an enormous human cost.

Dupont Plaza, San Juan

On Dec. 31, 1986, an arson fire at the Dupont Plaza in San Juan, tied to a labor dispute, tore through public spaces and left between 96 and 98 people dead, with about 140 injured. Smoke and toxic gases flooded the casino and lobby quickly, and rooftop rescues became part of the record as New Year’s energy turned into evacuation lines, burn care, and frantic headcounts at the curb. Often cited as the second-deadliest hotel fire in U.S. territory, it still shapes training because it shows how staffing, drills, and sprinkler readiness matter when fire moves faster than crowds can think. Even today.

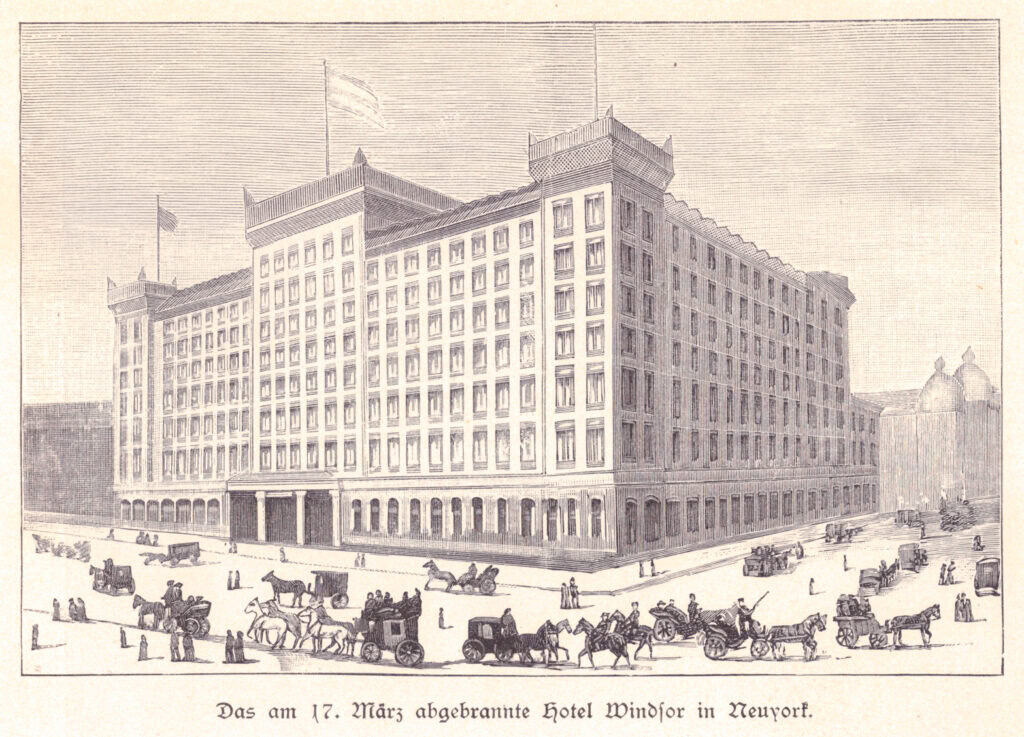

Windsor Hotel, Manhattan

On March 17, 1899, as St. Patrick’s Day crowds packed Fifth Avenue, the Windsor Hotel at 575 Fifth Avenue burned down in about 90 minutes and roughly 86 people died. Firefighters, some pulled straight from the parade, battled low water pressure and street congestion while guests tried ropes, fire escapes, and desperate jumps that ended on the pavement below. Many victims could not be identified afterward, and the loss exposed how luxury interiors, open voids, and weak fire separation can turn a prominent address into a fast-moving fire trap, fueling calls for stronger building rules and better hydrant pressure.

MGM Grand, Las Vegas

In the early morning of Nov. 21, 1980, a fire at the MGM Grand on the Las Vegas Strip killed 85 people, most from smoke inhalation, and injured hundreds more. The blaze began low in the building near a restaurant area, but toxic smoke traveled into the hotel tower and stairwells, reaching guests who never saw flames and could not read danger in dark corridors until it was too late. With thousands inside a 26-story resort later known as Bally’s and now Horseshoe, the aftermath reshaped Nevada’s approach to high-rise safety, accelerating sprinklers, alarms, and smoke-control retrofits. For decades.

Newhall House, Milwaukee

On Jan. 10, 1883, Milwaukee’s Newhall House caught fire and at least 70 people died, making it the deadliest fire in the city’s history. Guests woke to smoke and confusion, and rescues unfolded from windows and ledges as the six-story hotel turned into a torch visible across downtown, with famous performers like General Tom Thumb among those who survived. In the days after, counts shifted as names were verified, and the story lodged in local memory as proof that exits, night staffing, and early alerts matter more than any promise of comfort when a building fills with smoke fast in winter darkness.

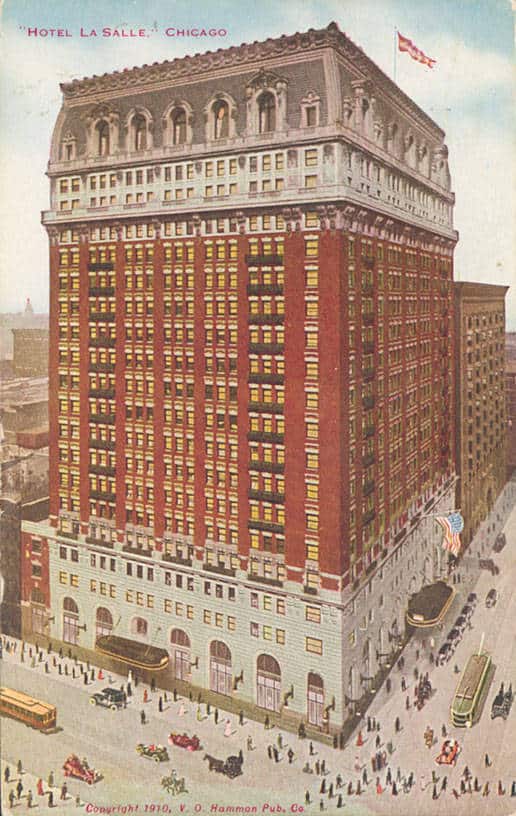

La Salle Hotel, Chicago

Just after midnight on June 5, 1946, a fire that began in the La Salle Hotel’s Silver Grill Cocktail Lounge spread through varnished interiors and up shafts, killing 61 people. Thick smoke did most of the killing, and while hundreds escaped into the Loop, others needed ladder rescues from windows above streets filled with spectators, sirens, and drifting ash, with accounts crediting sailors with pulling dozens to safety. The hotel had marketed itself as safe, but the aftermath pushed Chicago to tighten codes, improve alarm notification, and treat in-room fire instructions as a basic promise, not a perk.

Gulf Hotel, Houston

In the early hours of Sept. 7, 1943, Houston’s Gulf Hotel in downtown Houston near the bus depot caught fire and 55 people died, many renting low-cost beds and cots. Thin wooden partitions and crowded sleeping areas helped smoke move quickly, and once the halls filled, escape routes narrowed to fire escapes, windows, and terrible timing. Many guests were elderly or transient, some paying 20 to 40 cents a night, and dozens had no one nearby to claim them, which led to mass burials for unidentified victims, Red Cross support for funerals, and a citywide reckoning about safety for the poorest rooms.

Mandalay Bay, Las Vegas

On Oct. 1, 2017, Mandalay Bay became tied to national trauma when a gunman fired from a 32nd-floor room into the Route 91 Harvest crowd of about 22,000 people across the street. Sixty people were killed, at least 413 were wounded by gunfire, and the total injured climbed far higher as panic ran through the festival grounds and nearby streets. The resort did not burn or collapse, yet its height and privacy became part of the mechanism of harm, pushing hotels and venues to rethink room access, surveillance, and emergency coordination when violence arrives without warning in a city built for crowds.

Other Blog Posts You Might Enjoy

www.idyllicpursuit.com (Article Sourced Website)

#Famous #U.S #Hotels #Deaths #Occurred #Idyllic #Pursuit