On this date in 1869, the Knights of Labor were founded in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. The organization grew slowly, but by the late 1870s, the Knights had become the nation’s largest labor union, remaining so until 1886. This was the first serious organization to bring in masses of workers into a single union to try and change the lives of the collective working class. It did not work out and in ways that would demonstrate the limitations of organizing in America and the harsh response of corporate America to worker organizing.

Labor was at a crossroads in post-Civil War America. The Civil War helped spur the growth of large factories, and capitalists like John D. Rockefeller began expanding their economic reach into what became the monopoly capitalism of the Gilded Age. Workers found the ground caving under their feet. Working-class people began criticizing the new economic system, but it took several decades for modern radicalism to become a common response for the working classes. All sorts of ideas were floated out there. Henry George had his single tax. Edward Bellamy wrote Looking Backwards and Americans were deeply taken with the work that promised a social revolution without class conflict.

As Leon Fink notes in his classic treatise on the Knights of Labor, Workingmen’s Democracy, labor was not in 1869 nor in 1885 at a point where revolutionary consciousness was really on the table for most workers. They were essentially pre-Marxist critics of the growing wage labor system. They rejected that system, but also called for the operation of “natural law” in the marketplace and did not reject the idea of profit. They believed in an idea of balance between employer and employee, but recognized that this balance had been thrown out of whack by the massive aggregation of capital into the hands of the few. These were people who had come of age during the Civil War and the rhetoric of slavery was strong with them. So terms like “wage slavery,” which the South had used effectively to critique northern labor relations in the 1850s, meant a lot to working people in the early Gilded Age. They felt they had become involuntary servants to wage labor and thus the system needed to be abolished like African slavery during the war.

This does not mean that Knights were not radical for their time. Fink makes a strong case that they indeed were radical in their own terms, rejecting the fundamental economic relationship of their time for a vision of the “nobility of toil” and a respectable working-class life that encompassed everyone who “worked” in their view — which was basically all but bankers, speculators, lawyers, liquor dealers, and gamblers. These were the groups feeding off the blood of the working man either financially or morally. Capitalism itself meant not a system of economic gain based upon profit, but the systematic exploitation of working-class people. This meant that you could be a business owner and be a workingman if you treated your labor with respect.

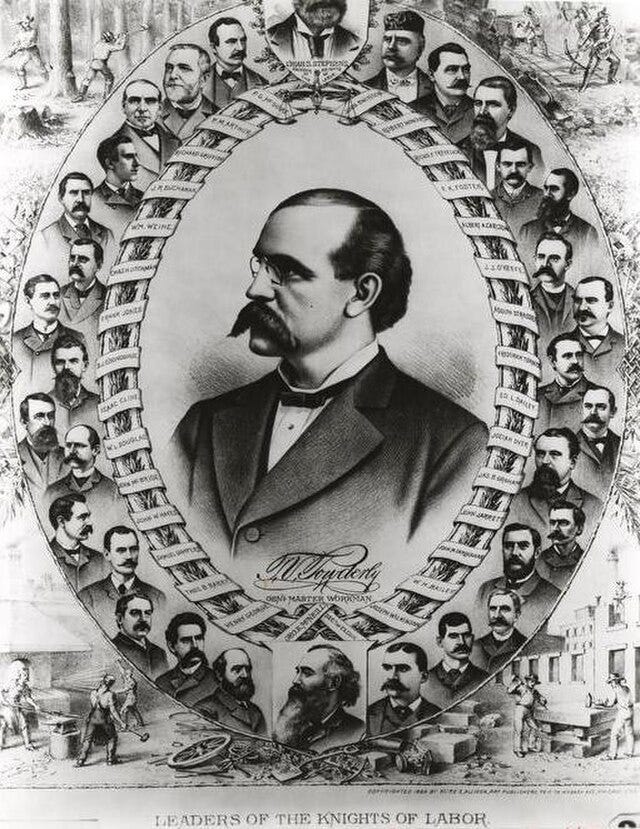

The Knights was essentially a working-class fraternal organization in its first years. But in 1879, Terence Powderly took over the organization. The mayor of Scranton, Pennsylvania, Powderly was as unclear as many workers on how labor should fight the growth of monopoly capitalism. He opposed strikes, even though he did occasionally engage in them as the Knights grew. He was however a superb organizer and could keep this unwieldy organization alive in the first years of its rapid growth, though his actual authority over what chartered locals did was very limited.

Powderly eschewed electoral politics despite his own history, noting the failure of the Greenback-Labor party in the late 1870s and the extreme corruption of Gilded Age life. This led Powderly and other Knights leaders to believe that electoral politics was a dead-end for the working class. But the huge growth of the Knights after the Panic of 1883 led to a rethinking of this idea precisely because the organization grew so large that many wondered if it could take over American political life. By 1886, the Knights began running labor tickets for office around the country, winning many races. This fell apart soon after due to right-wing backlash and infighting, but suggested the power of labor to transform American life if it were organized.

By the mid-1880s, new elements were entering the American working class. The rapid growth of European immigration after 1880 brought new ideas into the Knights, ideas that did not make people like Terence Powderly comfortable. The simple and eloquent platform of the eight-hour day galvanized working-class people across the country, many of whom joined the Knights for this reason but sought to make the organization their own.

This included anarchists, a political ideology new to American shores at this time that was popular especially with German workers. This brought the tricky issue of immigration to the fore. The Knights largely did not believe that Eastern Europeans could be acceptable independent American laborers and they definitely did not think the Chinese could be. They did however have some tolerance for organizing Black workers because they had been in the United States long enough that they had learned enough about the supposed values of American respectable work the Knights treasured. They were generally fine with Germans, but were very much not fine with this kind of radical ideology, at least at the leadership level. So there were inconsistencies at the heart of the Knights’ efforts to bring all workers into a single union.

These new immigrants flocked to an organization that supported their dream of an eight-hour day. Given the decentralized nature of the Knights, anarchists could participate in the Knights even if Powderly directly opposed their ideas. In Chicago, the growing German anarchist community played a minor role in the eight-hour movement until one act made them synonymous with the 1886 strikes. In response to the killing of two striking McCormick Harvesting Machine workers by cops, the Chicago anarchists movement called for a large demonstration. Although turnout was small, it became one of the most important events in American labor history when an unknown anarchist (still unknown today) threw a bomb into a crowd of police officers, killing eight. The police then fired into the crowd, killing eight strikers. Leading anarchists were arrested, thrown in jail, convicted, and four were executed. The Haymarket bombing and the police repression in its aftermath would become an internationally celebrated incident.

The Knights declined precipitously after Haymarket. Powderly was not ideologically prepared for mass violence nor for radical ideologies. The crushing of the Knights and the eight-hour movement after Haymarket left Powderly without much direction on where to take the organization, and workers left it as quickly as they had joined the year before. Employers would stop at nothing to crush the Knights organizing their workforces. The American Federation of Labor would soon rise to become the dominant working-class organization in America, but its conservative bent excluded the mass of unskilled and often foreign-born industrial labor that lent such immediacy to the eight-hour day campaign of 1886. These workers would fight and die for another half-century before successfully unionizing.

Powderly remained active in labor issues throughout his long life. Although he had headed the first large radical organization in the United States and was mayor of Scranton on the Greenback-Labor ticket, he was fundamentally conservative and became a Republican. He continued to oppose immigration and had supported the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882. He and William McKinley became close; McKinley named Powderly US Commissioner General of Immigration in 1897 and he remained a high-profile immigration official until 1921 with the exception of a few years in the mid 1900s.

FURTHER READING

Leon Fink, Workingmen’s Democracy: The Knights of Labor and American Politics

Kim Voss, The Making of American Exceptionalism: The Knights of Labor and Class Formation in the Nineteenth Century

Joseph Gerteis, Class and the Color Line: Interracial Class Coalition in the Knights of Labor and Populist Movement

Robert E. Weir, Beyond Labor’s Veil: The Culture of the Knights of Labor

James Green, Death in the Haymarket: A Story of Chicago, the First Labor Movement, and the Bombing that Divided America

www.wonkette.com (Article Sourced Website)

#Time #Knights #Labor #Invented #Union #Workers