It’s 11:30 in the morning on a sunny Friday in Vancouver’s Mount Pleasant neighbourhood and TJ Felix has already injected enough fentanyl and methamphetamine to kill most people, but years of drug use have raised the 36-year-old’s tolerance to unthinkable heights.

The potentially deadly cocktail — known as “speedball” on the streets — is the only thing keeping Felix from experiencing the dangerous and painful symptoms of drug withdrawal.

“I would kill myself if I had to go through intense withdrawal again,” said Felix. “It’s something you avoid at any cost, and the worst, deepest level of addiction is when you’re just using to avoid that.”

“It’s no life at all really when it revolves just around you not being sick,” Felix said.

Felix, a two-spirit artist and musician from the Splatsin First Nation near Shuswap Lake in B.C.’s Interior, has been exposed to drugs and alcohol since they were nine years old. They moved to Vancouver in 2007 and attempted treatment several times, but it wasn’t until they were part of a compassion club that provided a safe supply of heroin that they were able to stabilize.

Over several weeks, Felix allowed journalists from the fifth estate inside their life to help understand the impact a safe drug supply had for someone addicted to illicit drugs — and how that changed when their access to that supply was cut off in 2023 and they turned to fentanyl to stave off withdrawal symptoms.

- Watch the full documentary, “The War on Safe Drugs,” from the fifth estate on YouTube or CBC-TV on Friday at 9 p.m.

The fifth estate obtained internal Health Canada reports that reveal the federal government was advised by its own experts to expand access to a greater range of safe and regulated drugs for people across Canada but that instead, at the height of the opioid overdose crisis, the government’s support for safe supply programs was watered down and eventually ended in March.

The internal documents reveal that in 2023 experts told Health Canada to support non-medical safe supply, such as legal and regulated compassion clubs. Months later, two people were arrested and charged with drug trafficking for opening a compassion club that was trying to save lives.

The origins of safe supply

Since 2016, more than 53,000 people across Canada have lost their lives to a drug overdose, according to data from the Public Health Agency of Canada. An average of 18 people are dying every day.

The majority of these deaths have been from fentanyl, a synthetic opioid 100 times more potent than morphine that is used in hospital settings and to manage chronic pain, but that is also manufactured illegally and sold on the street.

As the drug took over the street supply in 2016, physicians from Vancouver to London, Ont., began prescribing hydromorphone tablets to their patients in the hopes that a pharmaceutical drug with a predictable dose would be safer than street drugs laced with unknown quantities of the much more potent fentanyl.

Hydromorphone tablets, also known by the brand name Dilaudid, were cheap to dispense and were already familiar to people who bought street drugs — on the illicit market they are often called “dillies.” The goal of prescribing them wasn’t to get people off drugs and into treatment. It was to keep them alive and away from the toxic street supply.

Pandemic pushes governments to prescription pills

After the B.C. government developed guidelines for prescribing pharmaceutical alternatives to people with opioid use disorder, the number of clinicians prescribing hydromorphone tablets grew quickly — by late 2022, the pills were being dispensed to more than 4,000 British Columbians every month, according to surveillance data from the B.C. Centre for Disease Control.

But the program didn’t work for everyone.

Aware of how dangerous the fentanyl-laced street supply had become in Vancouver, Felix tried to get access to a safe supply of prescription drugs through their doctor.

“I realized that if I kept accessing that same dealer and those drugs, that it was going to kill me. I went to my doctor and asked for a safe supply and they did so, but it capped at like a very little amount that wasn’t nearly enough.”

This experience is no surprise to Jordan Westfall, who wrote a master’s thesis in 2015 about overdose prevention in British Columbia.

Westfall’s academic background — and his personal battle with an addiction to street drugs — led him to believe that for people to stop using and dying from illicit drugs, there needed to be drastic change to federal drug policy.

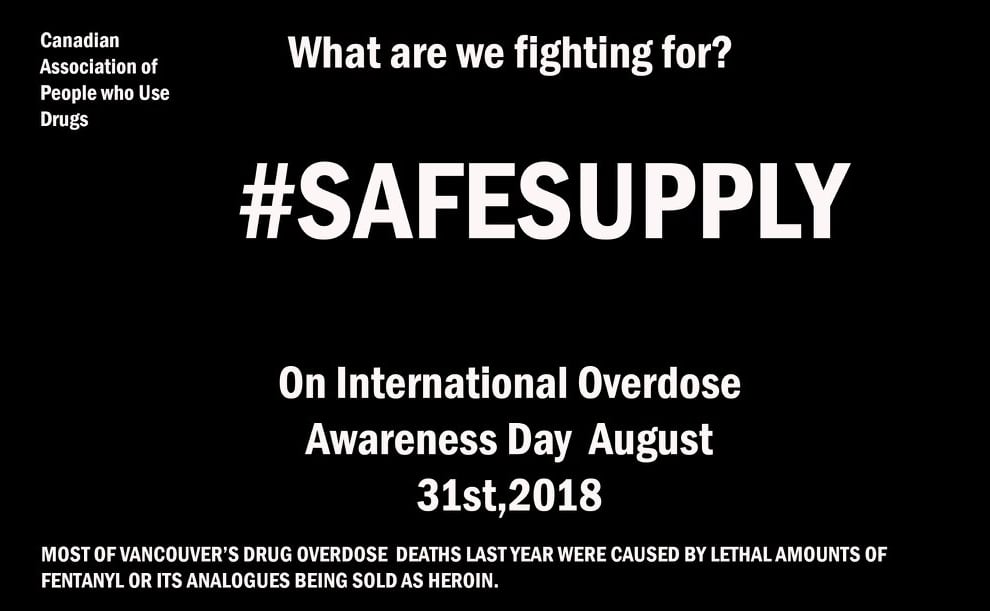

In 2018, Westfall and an organization of drug users advocating for themselves called the Canadian Association of People who Use Drugs (CAPUD) took out a full-page ad in a Vancouver newspaper. At the top of the page were two words in a large font: SAFE SUPPLY.

“It seemed very clear to me that everybody was using these drugs, that they didn’t really know what was in them,” said Westfall. “When you know what they are and they’re predictable, you’re way less likely to overdose.”

For CAPUD, safe supply meant providing a legal and regulated supply of drugs like opioids, stimulants and hallucinogens.

“This idea caught on pretty quick,” said Westfall, who was executive director of CAPUD at the time. “Within a year of us sort of launching this term ‘safe supply’ I was talking to the prime minister about it.”

In 2019, Westfall was invited by Health Canada to join its Expert Advisory Group on Safer Supply and was eventually made co-chair of the group.

But Westfall said he began to feel isolated after realizing not all committee members shared his vision of safe supply: providing access to legal and regulated versions of drugs like heroin, fentanyl and cocaine.

Instead, Health Canada spent $127 million to fund 31 pilot programs across the country that provided safe supply to people with opioid use disorders. In most cases, they were provided with hydromorphone tablets.

According to Westfall, the committee warned in 2019 that the tablets, which contain doses of up to eight milligrams of hydromorphone, were likely nowhere near strong enough to match the street drugs laced with fentanyl that people were used to.

“It’d be like if you have a cup of coffee every morning and we took your cup of coffee away and just gave you a teaspoon of coffee and said, ‘Try and start your day with that,’” said Westfall. “For most people, it wouldn’t work.”

Experts’ advice not implemented

Health Canada has not made public any advice from the internal report that came from its committee of experts.

However, the fifth estate has obtained unredacted copies of two final reports produced by the committee in 2023 that show the experts called on Health Canada to take action to expand safe supply.

The Phase 1 final report says safer supply should be expanded to include “a greater range” of not only prescription opioids, including injectable hydromorphone and heroin, but also stimulants like methamphetamine and cocaine.

The fifth estate found no evidence that the committee’s recommendations have been implemented by Health Canada.

“It was kind of heartbreaking because we had solutions that were available,” said Westfall about the lack of support for options like injectable heroin and hydromorphone. “We had evidence that showed them and it was being ignored and it was incredibly frustrating.”

Jordan Westfall, one of the co-chairs of Health Canada’s expert committee on a safe supply of drugs, says evidence-based solutions were ignored by the federal government.

In an emailed statement to the fifth estate, Health Canada said that it “has considered the [Expert Advisory Group’s] work alongside other input received from provinces and territories, addictions medicine specialists, law enforcement and additional stakeholders in developing approaches to prevent overdose deaths.”

Compassion club model rejected

A second final report obtained by the fifth estate also reveals experts advised Health Canada to offer a legal and regulated safe supply of drugs outside the medical system that would be overseen by a government agency.

In its July 2023 Phase 2 report, the committee of experts suggested that drugs of “known content and potency” could be provided to drug users at compassion clubs, buyers’ clubs and regulated retail options that obtained a federal exemption to the Controlled Drug and Substances Act.

However, in 2022, Health Canada denied the founders of a Vancouver compassion club an exemption to the act. They were later arrested and charged.

Last Friday, the founders of the Drug User Liberation Front (DULF) were found guilty of three counts of possession for the purpose of trafficking for selling drugs out of a storefront in Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside.

From August 2022 to October 2023, Jeremy Kalicum and Eris Nyx ran a compassion club that bought heroin, cocaine and methamphetamine through the dark web and tested the drugs for dangerous contaminants in university labs before clearly labelling them and selling them to members.

Their operation had the support of local authorities like the City of Vancouver, Vancouver Coastal Health and the B.C. Centre on Substance Use as well as exemptions to federal drug law that allowed it to collect, store and test illicit drugs.

But a B.C. Supreme Court judge found them guilty because they went a step further in selling, or giving away, the drugs to club members.

In August 2021, the Drug User Liberation Front had sent an urgent request to Health Canada and Patty Hajdu, then the federal health minister, asking the federal government to grant an exemption to the Controlled Drug and Substances Act to allow them to buy and sell uncontaminated drugs out of a storefront in Vancouver.

“We wanted to get a realistic picture of what would happen if people had access to a regulated supply of substances that they had to purchase,” Kalicum told the fifth estate.

In July 2022, Health Canada sent DULF a letter rejecting their request for an exemption.

“Health Canada cannot approve your proposed model of purchasing drugs over the dark web because of the associated public health and safety risks,” wrote Jennifer Saxe, the director general of Health Canada’s controlled substances directorate.

Kalicum and Nyx immediately filed an appeal of that decision, which has still not been resolved.

They opened the compassion club in 2022 worried that more lives would be lost if they waited for the outcome of their appeal. That year alone, figures from the B.C. Coroners Service show 2,388 people had died of overdose in the province.

“We saw that people overdosed way less. We didn’t have anybody die,” Kalicum told the fifth estate.

“We saw people that were accessing the club stop using drugs once they were able to gain that stability and not have to be kind of flailing around trying to find substances or getting ripped off.”

Compassion club co-founder Jeremy Kalicum says members of the group benefited from having access to a predictable and uncontaminated supply of drugs such as heroin, cocaine and methamphetamine.

Felix was one of 47 people who were part of peer-reviewed studies conducted by DULF.

“I’d be dead 10 times over if it wasn’t for them,” they said. “I can’t stand the thought of my friends going to jail for this. For saving lives. For saving my life.”

But when Kalicum and Nyx were arrested and DULF was shut down, Felix lost access to their only predictable source of drugs.

“I started going into a panic,” Felix told the fifth estate. “All I could think to do was to buy fentanyl, and I’d never used fentanyl in my life. I had no idea how to use it, how much to use.”

“For the next two months after that, it was all in a fog of paranoia and drug ODs,” said Felix. “I think I overdosed at least once a day.”

Vancouver artist TJ Felix says having access to a safe supply of drugs is a matter of life and death for them.

Kalicum and Nyx have filed a constitutional challenge that argues their Charter rights and the rights of drug users were violated when the club was shut down because it was providing life-saving services in an emergency situation. The first hearing in that challenge is Nov. 24 in B.C. Supreme Court.

They say they’re willing to take their fight all the way to the Supreme Court of Canada.

Government backtracks on safe supply

Despite recommendations from Health Canada’s expert committee that the federal government take the lead on expanding access to more pharmaceutical drugs in safe supply programs across Canada, Ottawa’s appetite for it seems to have died out.

There is no national safer supply program and Health Canada says its funding for 31 prescribed safe supply programs ended in March as planned. The federal government no longer has a Ministry of Mental Health and Addictions.

The current federal health minister, Marjorie Michel, declined the fifth estate’s request for an interview about safe supply.

In an emailed response, a Health Canada spokesperson said projects providing prescription alternatives to street drugs “were one activity within a whole of government response to the overdose crisis.”

The fifth estate also sent interview requests to former officials who would have had influence over Canada’s stance on safe supply policy, including former prime minister Justin Trudeau, former minister of mental health and addictions Carolyn Bennett and Canada’s former chief public health officer, Theresa Tam. All declined to be interviewed.

On Oct. 31, the fifth estate attended a Health Canada media conference that promised “funding to help address the toxic drug and overdose crisis in Ontario.”

Health Canada earmarked more than $36 million for projects aimed at substance use, but none of them mentioned providing access to a safe and regulated drug supply.

Fifth estate co-host Steven D’Souza asked parliamentary secretary Maggie Chi if the federal government still supports providing people at risk of overdose a safe supply of drugs.

People like Felix are at the mercy of the political debate over whether to provide drug users with legal, regulated alternatives to illicit drugs. Without a safe supply, they feel they have no choice but to continue to rely on potentially deadly street drugs to stave off the sometimes deadly symptoms of withdrawal.

“If we ever hope to have capacity or to work on ourselves and to even think about recovery, we need to be given some grace,” said Felix.

www.cbc.ca (Article Sourced Website)

#Theyre #risk #dying #opioid #overdose #government #cut #funding #CBC #News