Every summer, I find myself escaping into the pages of a certain novel like clockwork: Minae Mizumura’s “A True Novel.” Its evocative, heady depiction of the summer resort town of Karuizawa in Nagano Prefecture, more of a supporting character than a mere backdrop for the human drama that unfolds, draws me in to almost forget, for a moment, the relentless humidity of a Tokyo summer — as if I, too, am cooling off under the shaded mountain roads of the summer resort town.

It is difficult to summarize “A True Novel,” published in 2002. At its heart, it is a love story that delves into the transformations Japanese society undergoes in the postwar era, centering on the shifting fate of one affluent family and those around them that get caught up in the tide.

I have to confess that, much like one of the book’s narrators, I have struggled to shake off the story and have found myself, more than once, visiting Karuizawa to attempt to retrace the characters’ steps, wondering if I might come across the two dilapidated Western-style summer houses whose images remain etched in my mind as if they were a specter of the town’s true past.

“A True Novel” by Minae Mizumura

Going to Karuizawa, you can’t help but wonder if you will stumble upon a version of the town as it has been mythologized on the page by any number of Japanese writers. Throughout its history, it has attracted greats such as Natsume Soseki, Ryunosuke Akutagawa and Yasunari Kawabata, all of whom were known to spend their summers in the area.

Beyond how it is depicted in fiction, it is the real-life Karuizawa — its history and present — that has the power to elicit an inherited nostalgia among its visitors. For one summer afternoon here, I sat with Mizumura, 74, to discuss the significance and draw of the area for her in both her fiction and in her reality, as the place where she pursues her craft.

Writing in Japanese

For those unfamiliar with Mizumura or her work, she describes herself as “a Japanese writer who grew up in America from the age of 12, received education in the States, came back (to Japan) and is writing in Japanese.” There is something deceptively simple in the way she represents herself but beyond its surface lies a central truth to her writing career that begins with her return to and reckoning with Japan.

Mizumura’s choice to write in Japanese, despite being educated in English, was fueled by a certain appreciation for the language. She explains that she has “always been interested in reading and writing in Japanese.” Being familiar with multiple languages — she also studied French literature at Yale for her graduate studies — means that she is always highly aware of the specific experience of the language she is working in, describing herself as “a very conscious writer.”

However, her focus as a writer in Japanese is not limited to language but also speaks to both a deep appreciation for the Japanese literary canon and a longing for the country of her birth throughout her time in the U.S. (It was reading Japanese literature during this period that kept her linguistically and culturally connected to Japan.) From the critical reception of her debut novel, a reimagining of Soseki’s final work titled “Light and Darkness Continued” (1990), and her bilingual exploration of a Japanese literary genre titled “An I-Novel from Left to Right” (1995) to her critical nonfiction work “The Fall of Language in the Age of English” (2008), Mizumura’s contributions to Japanese literary canon have always served as both careful reflection and a kind of intervention.

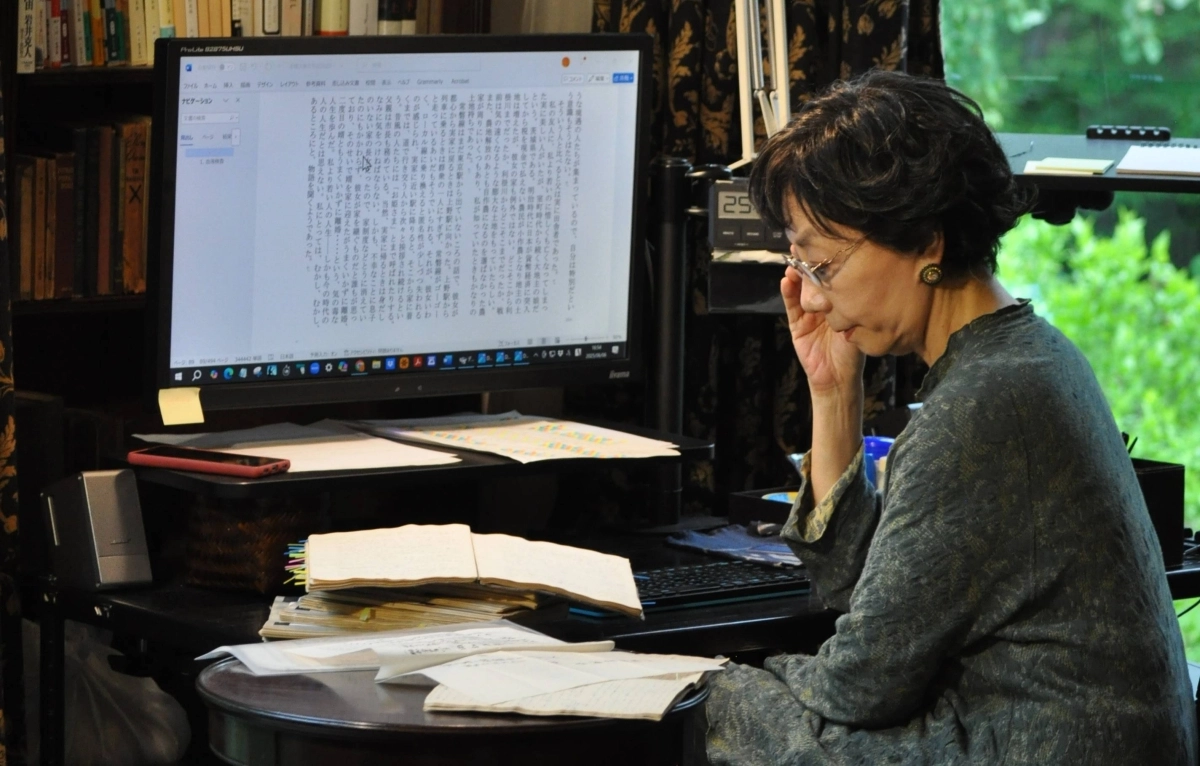

Minae Mizumura works at her desk at her cottage in Karuizawa, a popular summer retreat for Japanese writers.

| TOYOTA HORIGUCHI

It was during her research on literary theorist Paul de Man at Yale that Mizumura arrived at the principle that drives her entire oeuvre: Literature always comes from the text — or more specifically, from other texts. Intertextuality, and the way different texts relate and speak to one another, is apparent in her work not only in how her novels speak to other writers’ work but also to each other.

It might not be wrong to think of Karuizawa as a kind of “text,” caught in a kind of intertextual play: repeatedly evoked by writers, constantly reshaped and reinterpreted, and imbued with layers of shifting meaning.

On writing Karuizawa

In his 1986 book “My Life Between Japan and America,” the diplomat and educator Edwin O. Reischauer wrote: “Summers in Karuizawa were not just a break in the year but seemed a whole lifetime in themselves.”

Once a post town on the historic Nakasendo trail, Karuizawa was first popularized as a summer resort town during the Meiji Era (1868-1912) by visiting missionaries and diplomats. It soon developed into an international community that also attracted Japanese elites and intellectuals. The area became synonymous with a certain kind of aspirational, Westernized, upper-class lifestyle. Famously, the imperial family would spend their summers in the area, and the exclusive tennis courts here are where Emperor Emeritus Akihito and Empress Emerita Michiko are said to have first met.

The area is now a popular tourist destination, with visitors drawn to its Western atmosphere — a reflection of the mixture of cultures that created the Karuizawa of today.

These exclusive tennis courts are where Emperor Emeritus Akihito and Empress Emerita Michiko are reported to have originally met.

| HANAKO LOWRY

In Mizumura’s work, the town plays the central locale in “A True Novel,” a retelling of Emily Bronte’s “Wuthering Heights” set in postwar Japan. She returns to the setting for her most recent novel, “The Ambassador and His Wife,” which was published last year but has yet to be translated into English.

It was through other writers’ depictions that Mizumura first encountered Karuizawa, but it was some time before she actually spent any amount of significant time here. After teaching at Princeton, she developed a habit of taking long walks and upon returning to Japan sought a place to continue the practice. She found what she wanted in Karuizawa. This was more than 35 years ago, and she now splits her time between Tokyo and here.

“Where a writer works is very important … the ability to be able to distance yourself,” she explains. “Of course it’s not a luxury every writer can afford but… a lot of writers do similarly have this need to get away from everyday life.

“There are many writers who came here before me and wrote their works here. There is this evocative, abstract, almost spiritual element (to Karuizawa). And there is also nature to lift your spirits.”

Minae Mizumura says of Karuizawa, ‘This area has a special history, and when you touch on that history, you touch on a very critical history between Japan and the West.”

| TOYOTA HORIGUCHI

The cottage we’re now sitting in became, to quote the title of Virginia Woolf’s famous essay, Mizumura’s very own “room of one’s own” and is where she has written many of her works. Karuizawa also became a vantage point from which to gain distance from her busy life in Tokyo and holds a valuable perspective when it comes to the themes of her work.

“This area has a special history, and when you touch on that history, you touch on a very critical history between Japan and the West,” she says. “You can talk of Japan’s recent history from Karuizawa.”

It was because of this history that Mizumura chose Karuizawa as one of the key settings for “A True Novel.” The fictional author-like figure in the narrative frame describes how she encountered a story that resembled “Wuthering Heights” and recognized it as having the makings of a different novel. Similarly, when Mizumura herself considered how she could even approach writing a love story comparable to Bronte’s classic but rooted in Japan, a “true novel” in Japanese — the answer lay in Karuizawa.

“Here you could talk about love in the Western sense,” she says. “What might seem foreign can happen here.”

Visitors walk around Kumoba Pond in Karuizawa, Nagano Prefecture. The pond is referenced in Minae Mizumura’s “A True Novel.”

| HANAKO LOWRY

She explains that “Wuthering Heights” and other 19th-century novels were what Japanese writers would have encountered as Western literature following the Meiji Restoration of 1868. Inspired by the notions of romantic love found in their pages, writers, artists and intellectuals were then naturally drawn to Karuizawa — a place that seemed imbued with the same qualities. Whether this was the product of their projected fantasies or inherently true to the area is perhaps now hard to distinguish — where fact and fiction begins becomes difficult to define when it comes to Karuizawa.

Mizumura’s own novel features numerous locations in the town, from the bar at the historic Mampei Hotel to the scenic Kumoba Pond. This was a very deliberate decision: She wanted the novel, despite its “far-fetched” premise, to feel rooted in concrete reality. To heighten that sense, photographs of the locations — taken one summer by Toyota Horiguchi, a former Kyoto City University of Arts professor whom Mizumura met at Yale — are scattered throughout. These images, taken almost as evidence for the novel’s “real” unreality, depict the changing face of Karuizawa. Among them are shots of summer houses, nestled in leafy, secluded plots, that hint at the bygone summers of their former inhabitants.

Driving through the town’s backstreets, in an attempt to trace the locations photographed for the novel, it becomes clear that many of the houses Horiguchi captured have seemingly disappeared.

On writing Japan

Mizumura took a 12-year break between her last novel and “The Ambassador and His Wife” due to what she describes as an intensive period of working with her translator, Juliet Winters Carpenter, on the English versions of her previous works. During that time, she often turned to rereading Junichiro Tanizaki and was struck by his later work, which also wrestles with the idea of a Japan that no longer exists.

This led her to become fixated on one specific image: a woman dancing in the style of noh by the moonlight. She made it her goal to write the scene into reality. The answer, once again, lay in Karuizawa — a place where “the mixture of the unbelievable and believable” is possible.

And so, “The Ambassador and His Wife” began to come into being.

At around 750 meters long, the Old Karuizawa Ginza shopping street has numerous bakeries and gift shops as well as a tourist information center.

| HANAKO LOWRY

Mizumura draws upon current events, including the COVID-19 pandemic, to anchor the novel in the present. Interestingly, she explores the meaning of an “authentic” Japan through the perspective of an American man who has lived in the country for decades — a point of view she says she had long wanted to write from. The character also resembles what she calls her ideal reader: someone familiar with both Japanese literature and the world outside of Japan.

Perhaps that reader also mirrors the author herself: Mizumura writes in a way that speaks to a certain kind of diasporic subjectivity — someone within and without the world they half-inhabit. It’s a mindset always half-longing for a Japan that exists in memory alone. She recalls someone from her time in the U.S. that told her this longing for Japan reminded them of the Nikkei community in Brazil, whose reality Mizumura explores in the novel.

Thus from Karuizawa, the perspective of an American Japanophile and the Nikkei community, Mizumura’s writing continues to explore representations of Japan in various forms, crafting an intimate, prismatic vision that is informed by that inherited nostalgia and which you can’t help but think to attribute, in part, to her own writing career rather than began with her “coming back” to Japan.

On writing a life

Mizumura’s original decision to write in Japanese rather than English was a commitment to write without first catering to global audiences. Still, her work, like that of many contemporary Japanese writers, has reached readers abroad by way of translation. Compared to her views in “The Fall of Language in the Age of English,” she says she now feels more optimistic about the future of Japanese literature.

“I wrote ‘The Fall of Language’ thinking that it would only reach a very small audience,” Mizumura says. “All I want now is for some Japanese writers to write without being interested in being translatable.”

As for the “lost” Japan imagined by the American protagonist in her latest novel, Mizumura says she is more accepting of how Japan is changing now than when she first returned from the U.S. Still, she hopes more government funding will be used to “preserve that knowledge” of traditional Japanese culture and art forms for future generations.

Though she considers her latest novel to be her final work of fiction, Mizumura says she is now focusing more on the act of writing memoirs — a natural shift in Japanese literary tradition, she notes, for writers who reach a certain stage. She shows me family artifacts and carefully archived memorabilia in preparation for her next project.

In part, this shift is well-timed. With the rise of generative AI, lived experience is something machines cannot replicate. “There is a kind of appreciation of art forms that can only come with age (in Japan),” she says, citing traditional dance and noh. “That is something AI can’t replicate.”

The sun’s position in the sky has slowly shifted throughout the course of our conversation and the evening’s light has begun to color the living room in shades of twilight.

“I am sure AI will write wonderful stories in the future,” Mizumura says, pausing a moment before continuing. “I am glad I am shifting to memoir and writing my life’s stories as AI cannot write them with the same humanity.”

www.japantimes.co.jp (Article Sourced Website)

#reality #fiction #summers #day #Karuizawa #Minae #Mizumura