Japan has one of the oldest populations on the planet, with women enjoying an average of 75.5 years of good health and men 72.6 years. Additionally, the country boasts more than 95,000 centenarians, a number expected to grow as people live longer.

Yet, beyond the statistics lie individual stories. Each centenarian is a living testament to history, having witnessed world wars, a postwar economic miracle, the rise of computers and the internet, as well as profound societal change.

Now, this generation is quietly redefining what it means to be old — not by retreating from the world, but by remaking it in their image: a world of purpose, creativity and reinvention.

Last month, The Japan Times visited five centenarians in and around Tokyo to get a sense of how people who have lived as long as they have conduct their everyday business. Also present was German photographer Karsten Thormaehlen, who has shot portraits of hundreds of centenarians around the world. He is currently working on a follow-up to his seminal 2017 photo book, “Aging Gracefully.”

Mayako Muroi, 104, can still remember touching her first piano almost a century ago.

| KARSTEN THORMAEHLEN

Mayako Muroi vividly recalls the shock she felt when she first touched a piano nearly a century ago. Her father bought her one when she was 6 years old — a rarity for girls in well-off Japanese families at the time, when many parents preferred the koto for their daughters’ musical education.

“A big black box arrived, and I was asked to hit a key,” recounted the 104-year-old Muroi, wearing a long gold sequined dress, at her home in Tokyo, where two grand pianos sit side by side. “When I pressed one, a big sound reverberated. I was so surprised I ran away. That was my first encounter with the piano.”

She soon became fixated on the instrument and has maintained a lifelong passion.

Mayako Muroi says she doesn’t think about her age, instead she’s too focused on what’s left to discover in the world of music.

| KARSTEN THORMAEHLEN

In 1956, Muroi broke with tradition by moving alone to Berlin at 35 — eight years before Japan lifted its ban on international tourism. At a time when solo travel abroad by Japanese women was almost unheard of, she struck out alone to enhance her performance skills.

Chosen to attend a recital commemorating the 200th anniversary of Mozart’s birth, she then studied under renowned pianist Wilhelm Kempff, solidifying her career in Europe until returning to Japan in 1980 at 59.

Despite a long music career, including a solo recital at 100, Muroi says her quest for better sounds remains unsated. To move people with music, we need to discover and appreciate the beauty of the sounds that their creators — whether Bach, Mozart or Haydn — tried to produce, not just master their techniques.

“I’ve never thought about aging,” she says, smiling. “I still feel there’s so much left to discover in music. My teacher once said I’d need to live to 200 to play something like Bach properly.” Now, she’s more than halfway there.

Shinobu Kani, 101, survived the war and became a corporate warrior in Japan’s postwar economic boom.

| KARSTEN THORMAEHLEN

At 101, Shinobu Kani is brimming with ideas to improve people’s lives. In fact, he is currently updating a patented pill separator he invented. Resembling a nail clipper, it is designed for older people who struggle to separate their pills from plastic packaging. “The joy of getting patents keeps me going. It’s more fun than business. … I have nothing better to do,” he says with a laugh.

Born in Sahara, Chiba Prefecture, Kani moved to Tokyo’s Minato Ward at 15, just as World War II was intensifying. He got a job at a factory assembling and painting radio equipment for the Japanese military while attending night school. Later, he was drafted to work at a military factory in northern Tokyo, manufacturing weapons and ammunition.

In the final months of the war, he transferred to Showa Denko’s Kawasaki factory. The firm was originally a chemical fertilizer maker but was repurposed by the government to produce gunpowder. It was during this time that he developed his inventive spirit, as engineers were forced to produce goods with dwindling materials.

He considers himself lucky not to have been sent to the frontlines and to have survived the U.S. air raids on Tokyo and Kawasaki. As bombs rained down on those cities, Kani recalls rivers and canals filled with the bodies of people, cows and horses piled atop one another — all desperate to escape the scorching heat.

Shinobu Kani shows off a new invention: A patented pill separator that resembles a nail clipper.

| KARSTEN THORMAEHLEN

After the war, he tried to rebuild his life by making metal cooking pots and pans, then venturing into parts and accessories for electronic products, such as stands for TV antennas. He was a typical corporate warrior whose efforts and ingenuity supported the rapid development of the postwar Japanese economy.

He continued working at his company until the age of 95 and developed a passion for mahjong, even obtaining a teaching certificate. Now, he fills his time coming up with inventions.

Kani counts his blessings. He lives with his 92-year-old wife, Kazuko, and has two sons, two grandchildren and one great-grandchild. He underwent major heart surgery at 92, and surprised many at the hospital by recovering quickly enough to leave intensive care the next day and begin rehabilitation within a week.

“If you fall ill and give in, that’s where life ends,” he says. “But if you find the strength to get back up, you keep going. Life after 80 is a cycle of repeating this.”

Hiroko Inoue, 106, still uses her home, which withstood bombing campaigns during the war, as an atelier.

| KARSTEN THORMAEHLEN

Though she has some hearing issues and takes time to collect her thoughts, Hiroko Inoue looks you straight in the eye when she answers questions, slowly but firmly.

The Yokohama-based painter, now 106 years old, lives in a wooden house that survived the fire bombings of WWII. In May 1945, B-29 bombers dropped over 400,000 incendiary bombs over Yokohama in the span of one hour, including five that directly hit Inoue’s home. She was pregnant at the time. Her sculptor husband, Nobumichi, suffered severe burns but survived by jumping into a nearby pond.

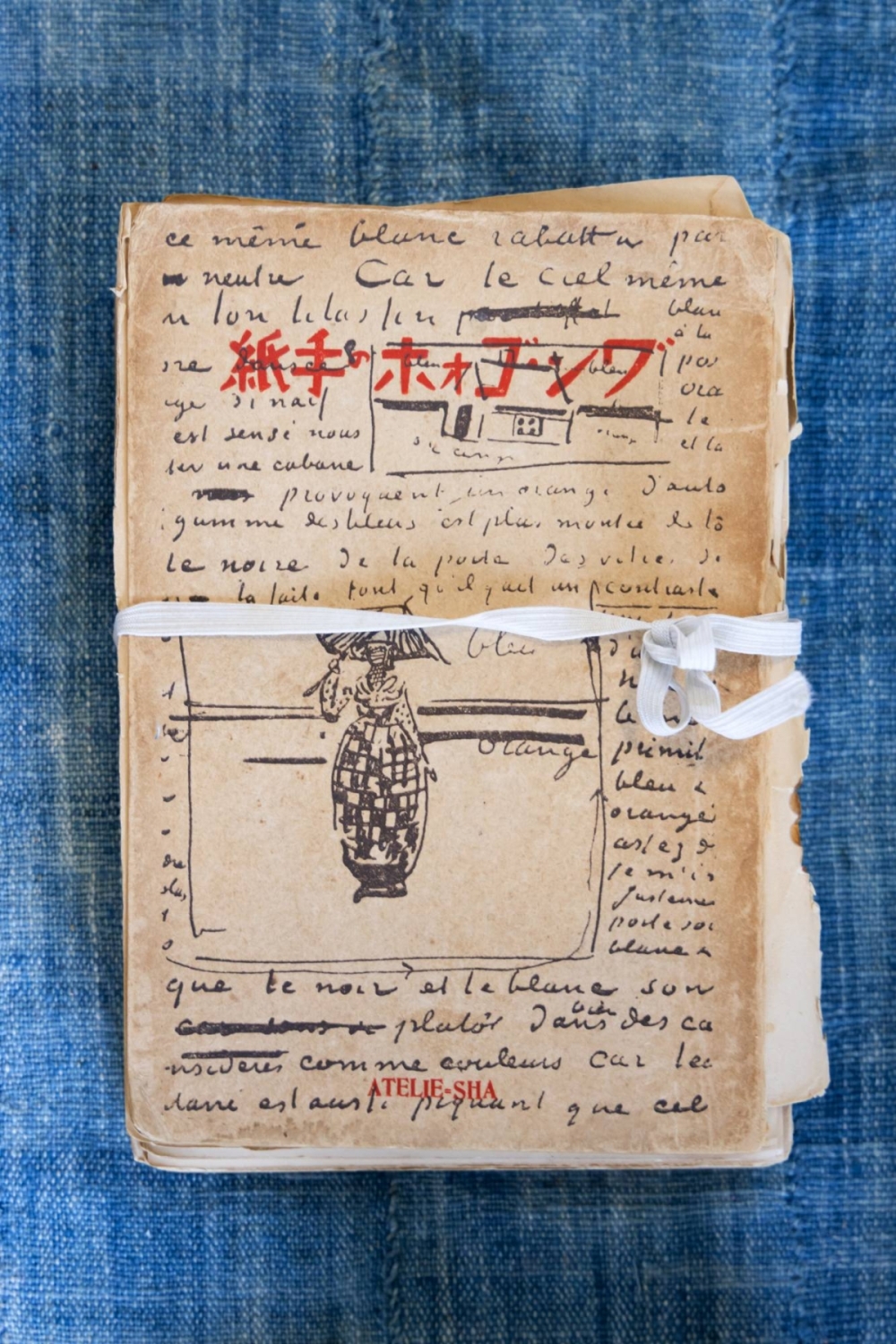

Inoue’s atelier, on the second floor of the structure that withstood the bombing, is filled with her art, Christian prayer books and handwritten notes in English. One message, taped inside a cabinet, reads: “People say that nobody left us forever.”

Nobumichi — whose works are held by several museums — died in 2008 at 99, but his first-floor atelier remains intact, occupied by numerous facial sculptures. A white circular patch on the ceiling reveals where he hastily applied sculpting plaster to seal a hole left by one of the bombs.

Inside Hiroko Inoue’s atelier are artworks, prayer books and handwritten notes.

| KARSTEN THORMAEHLEN

Inoue’s works, somewhat reminiscent of Van Gogh, range from abstract pieces to scenes inspired by European landscapes. A distinctive feature is her nuanced use of indigo blue — a color the late poet and sculptor Kotaro Takamura, her former neighbor in Tokyo’s Hongo district, encouraged her to explore.

Living with her daughter, Shizuko Ohno, also a painter, Inoue maintains an impressive posture. Ohno says her mother requires little mobility support and helps with washing dishes after meals.

“The other day, I made onion soup and chopped up some pasta to make it easier for her to digest,” Ohno says. “She added the pasta into the soup herself to make it even softer. It might not be proper table manners, but it shows how she thinks about how to keep living well.”

Asked why she keeps painting, Inoue pauses, then says, “Ideas for my paintings are all around me. I am surrounded by inspiration.”

After a moment of reflection, she adds, “Everyone has a reason to paint. … They just don’t think deeply about it. I sometimes find myself wondering about that very question while I’m in the middle of working on a painting.”

Masahide Shibusawa’s great-grandfather, Eiichi, is on the current ¥10,000 note.

| KARSTEN THORMAEHLEN

Masahide Shibusawa is the great-grandson of Eiichi Shibusawa, the industrialist known as the father of capitalism in Japan — and the face on the new ¥10,000 note that entered circulation last July. His father, Keizo, served as the governor of the Bank of Japan and finance minister during and after WWII.

Despite this privileged family background, Masahide, 100, says he spent his youth in great distress.

“I spent my first 20 years feeling depressed,” Shibusawa recalls at his Tokyo home. “I felt I was wasting my life just by being born Japanese. … I felt the whole country was headed in the wrong direction.”

Born in London, where his father worked for a private-sector bank, Shibusawa enrolled in the Imperial Japanese Army’s reserve officer cadet school in his late teens. During his stint, he witnessed Tokyo’s devastation by U.S. fire bombings.

After the war, he entered the University of Tokyo, majoring in agriculture — partly due to his family roots (his great-grandfather’s family ran an indigo dye and silkworm farming business in Saitama Prefecture) and partly because it was “the easiest to get into,” he says with a mischievous glint in his eyes.

After graduating, he held various jobs, including a several-year stint at a trading firm. He also led the MRA Foundation, the Asia hub of the Moral Re-Armament Movement, promoting international cultural exchange and world peace.

Masahide Shibusawa, now 100, is seen here as a baby. His great-grandfather Eiichi (left) is known as the father of capitalism in Japan.

| KARSTEN THORMAEHLEN

Following his father’s death in 1963, Shibusawa dedicated time to chronicling and archiving his family’s achievements.

“He was extremely busy at work and lived until 91,” he says of great-grandfather Eiichi, who is credited with helping set up 500 firms and 600 social enterprises in Japan. “He wasn’t so interested in (Western-style) capitalism, but he felt everyone needed to work together to make the country prosper. He didn’t want to be rich alone. He wanted everyone to be rich — an idea I greatly agreed with.”

Widowed but maintaining close communication with his daughter Tazuko, a scholar, Shibusawa believes Japan is a far better place now than in his youth.

“We are free now, we can do anything and there are more than enough opportunities to make the country better if you are serious about it,” he says. “I have lived a happy life. I was very unhappy for the first 20 years, but have lived a very happy 80 years.

“When you reach 80 or 90, things you used to enjoy — like mountain climbing and skiing — start to feel bothersome. But I’m still happy. Life is easier if you aren’t too greedy.”

Miwa Sanjo — who is 99 on paper but is thought to be older — was a born actor, often acting up for attention in her youth.

| KARSTEN THORMAEHLEN

Though she’s 99 on paper, Miwa Sanjo says her true age is unclear as she was born a few years before her birth was officially registered. One thing she’s certain of, though — she was a born performer.

“I was a theatrical child from early on,” she says with a grin. “My cousin used to joke that I started acting even as a baby, pretending to have a seizure if I didn’t get enough attention.”

Sanjo’s first brush with the stage came at age 6, when her father took her to see “The Lower Depths,” a play by Russian dramatist Maxim Gorky. She was particularly drawn to the character of Vassilisa Karpovna, a woman who conspires with her lover to kill her abusive husband.

“She was a strong, fabulous woman, and I love strong women,” Sanjo recalls of the character. “My mother, who was a medical doctor, was extremely worried about my exaggerated reactions to everything, which to her seemed like I was telling lies.”

Sanjo followed in her mother’s footsteps and became a doctor herself. After earning her medical license, she trained in otolaryngology at Keio University Hospital. She pursued her stage career after work. She joined the now-defunct Shin-Engeki Kenkyusho (New Drama Company) in the 1950s. For decades, she balanced dual careers — running a clinic in Shinagawa Ward while writing and performing original works for her own theater company, Group Shura. She has staged “The Lower Depths” many times — playing Vassilisa, her dream role.

Sanjo closed her clinic in 2022, after patient visits declined sharply during the COVID-19 pandemic. Still, she fields the occasional medical question from former patients.

Though she trained as a doctor, Miwa Sanjo’s true passion is the theater. She continues to write for stage and theater magazines in her old age.

| KARSTEN THORMAEHLEN

Meanwhile, her stage life continues. In January, she performed the lead in “Joyu” (“Actress”), a play she wrote about an aging performer who dreams of stardom on her deathbed. The role had eerie resonance: Sanjo had fractured her backbone the previous fall and hadn’t fully recovered. But because the character remained in bed for much of the play, the limitation worked in her favor.

Her repertoire also includes politically charged material, including a stage adaptation of “Unit 731,” based on Yoshiaki Hiyama’s 1980 novel about the infamous Imperial Japanese Army unit that conducted human experiments during the war. She regularly contributes essays to a theater magazine, and is also planning a poetry reading this summer to mark the 80th anniversary of the atomic bombings.

As a doctor, how does Sanjo explain her longevity? “I have no idea; I lived this long before realizing,” she says. “I never followed any health tips, I have lived my life the way I wanted.”

That includes a few unconventional stress-relief techniques. When things get too much, she shouts at full volume in her apartment at night, and has found throwing a box of rakugan (dry sweets made from sticky rice and sugar) on the floor so it shatters into pieces — and eating the pieces later — makes her feel better.

She also likes manga, particularly “Golgo 13,” a long-running series featuring an assassin for hire. “I love evil characters. That’s why I love the Vassilisa character (in Gorky’s play), too. I get to shout angrily. That’s been fun.”

There’s no single secret to reaching 100, though most centenarians have no trouble explaining how to enjoy life once you get there. Passion, rather than prescriptions, may be the key to staying healthy. It’s a piece of advice worth remembering as more of us achieve the same milestone.

www.japantimes.co.jp (Article Sourced Website)